Editor’s Note: The following essay is an edited excerpt of the Preface written by James Voorhies for Tony Smith Architecture Catalogue Raisonné Volume 2. Edited by Voorhies and Sarah Auld, the catalogue presents the full extent of production in architecture by Tony Smith. Combined with a companion publication Against Reason: Tony Smith, Architecture, and Other Modernisms, the two books devoted to architecture are part of the Tony Smith Catalogue Raisonné Project, which presents Smith’s complete oeuvre in sculpture and architecture. Published by MIT Press, the project is intended to position Smith’s transdisciplinary practice in dialogue with contemporary voices in art and architecture.

Figure 1: Tony Smith at Olsen Sr. House property, Guilford, CT, ca. 1951. © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

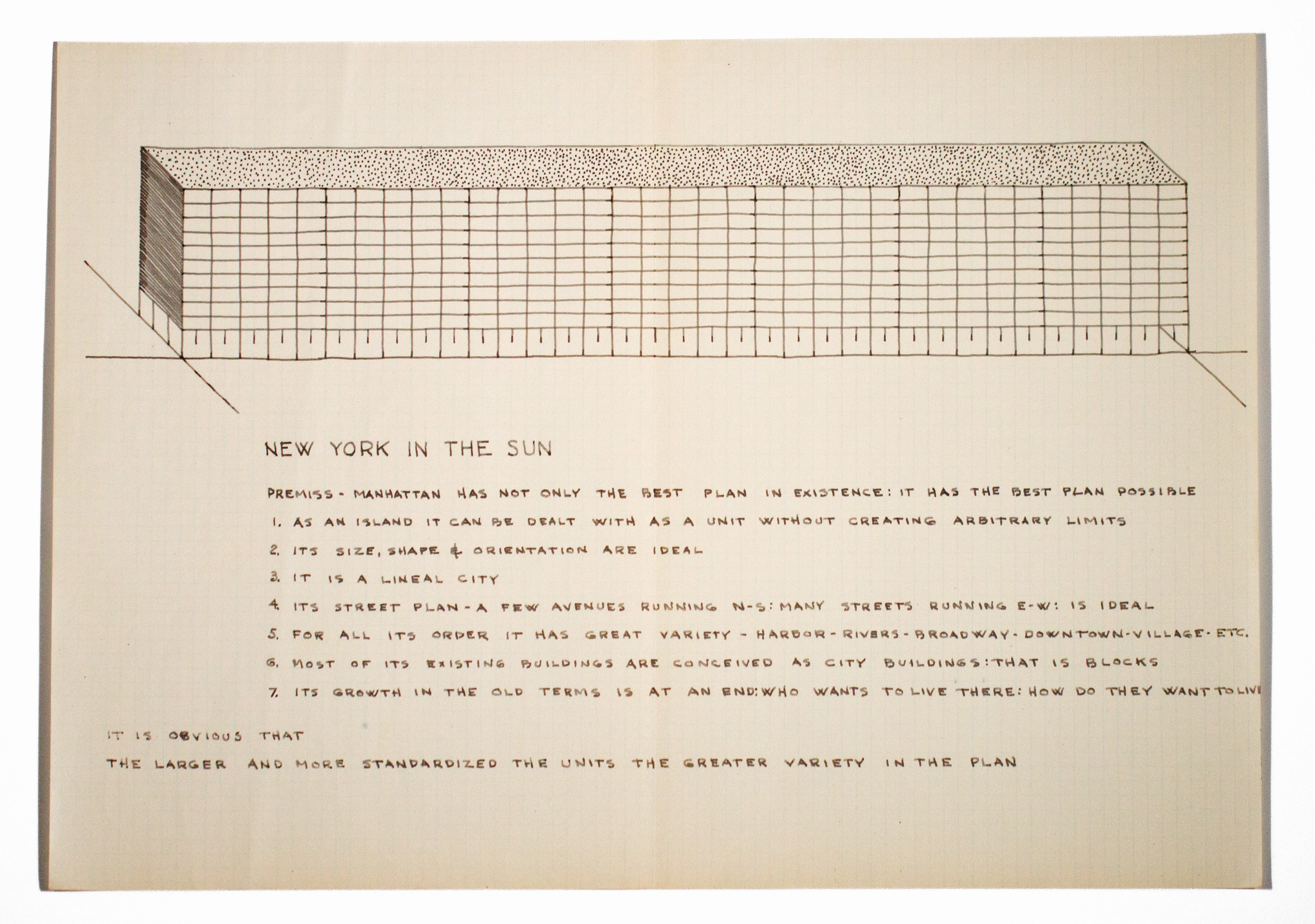

Tony Smith (1912–1980) was an architect. He was a thinker who experimented with urban planning, and he was interested in questions about civic space. He was an intellectual who looked to the history of art, literature, and design to reflect on the conditions of contemporary life. As a practicing architect, he built at least ten projects between the late 1930s and early 1960s. (fig. 1) He left an archive of drawings, notebooks, and sketchbooks of ideas for more than one hundred unbuilt projects, some of which were feasible residential architecture, others wonderfully impossible to realize—such as one titled New York in the Sun, (1953–55) that envisions Manhattan as a close-packed, singular solid hovering between earth and sky. (fig. 2) All are imbued with Smith’s advanced perspectives on the boundless potential of art, architecture, urban space, and landscape to coalesce and function together. An American modernist known for large-scale sculptures composed of polygonal building blocks, Tony Smith had, in fact, pursued architecture for over twenty years before turning his attention full-time to sculpture. The ever-shifting qualities of his large-scale sculptures—which engage the spectator in phenomenological experience, changing in relation to one’s motion, position, sightline, and perspective—cannot be considered in isolation from his work as architect. In fact, the early thinking he applied to architecture and design, combined with studies in mathematics, space, and volume, informed the entirety of his work and ideas throughout his lifetime.

BOTTOM: Figure 3: Robert and Mary Gunning House, Blacklick, Ohio, 1940. Smith van Fossen and Cuneo, exterior view, 2024. Photo Dorri Steinhoff. © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For readers less familiar with Smith’s architecture, his initial forays into design were influenced by his studies in 1937–38 at the New Bauhaus in Chicago with noted instructors Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), Hin Bredendieck (1904–1995), György Kepes (1906–2001), Henry Holmes Smith (1909–1986), and László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), who led the program, followed by a busy year serving as clerk of the works on Frank Lloyd Wright’s (1867–1959) residential project in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, then attending his Taliesin Fellowship in Green Spring, Wisconsin, in 1939. The style of Smith’s early houses mirrors both the form and content of Wright’s architecture. In 1940, in Blacklick, Ohio (just outside Columbus), the twenty-seven-year-old Smith designed and built his first house along with the nineteen- year-old architects Theodore van Fossen and Laurence Cuneo, whom Smith had met at the New Bauhaus. In this house for Robert and Mary Gunning, the young architects employed Wright’s Usonian principles: an open plan, carport, storage walls, solar heating, radiant heat, and a structure long and low to the ground, with a thin overhanging roof and narrow windows. (fig. 3) In 1944, Smith designed and built a house for his father-in-law, L. L. Brotherton, in Mount Vernon, Washington. The design of the Brotherton House uses a hexagonal grid as the primary planning device, visible in ground plan drawings for the 3,500-square-foot house and in finished diagonals that populate the interior. Smith’s geometric design recalls Wright’s references to molecular cell structures, like the beehive, signaling some of Smith’s conceptual and compositional underpinnings and motivations, and using geometric forms as foundational building blocks that would become so critical to his later sculptures. (figs. 4–5)

BOTTOM: Figure 5: L. L. Brotherton House, Mount Vernon, Washington, 1944–45. Smith van Fossen, interior view, 1948. Photo Chas. R. Pearson. © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

By the mid-1950s, as an independent architect, Smith had dispensed with Wright’s organicism, partially as a response to living in Germany and traveling through Europe, exchanging it for the formal principles of European modernism and the reductivist steel-and- glass structures of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) and Le Corbusier (1887–1965). Smith would merge the rationalism of the International Style with his enduring interest in the organic cohesion of modular forms. He would continue to consider the conditions of place as mediating between natural elements and abstract geometries, designing mostly private residences but also churches, public housing, visionary urban planning projects, and artist studios. Smith’s Olsen Sr. House (1951–53) consists of four buildings, three of which sit atop a cliff overlooking Long Island Sound, in Guilford, Connecticut. (fig. 6) The influence of Le Corbusier is evident in Smith’s use of pilotis (piers), comparable to those seen in Corbu’s Villa Savoye (1931) in Poissy-sur-Seine, France, or the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (1963) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Other references to Le Corbusier and even to Philip Johnson (1906–2005), whose Glass House was completed in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1949, are notable in the Olsen Sr. House, including the expansive open courtyard, large plate-glass windows, and spatial transitions and manipulation of geometries that would later characterize Smith’s sculpture.

Figure 6: Fred Olsen Sr. House, Guilford, Connecticut 1951–53, exterior view, 2005. Photo Dean Kaufman. © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

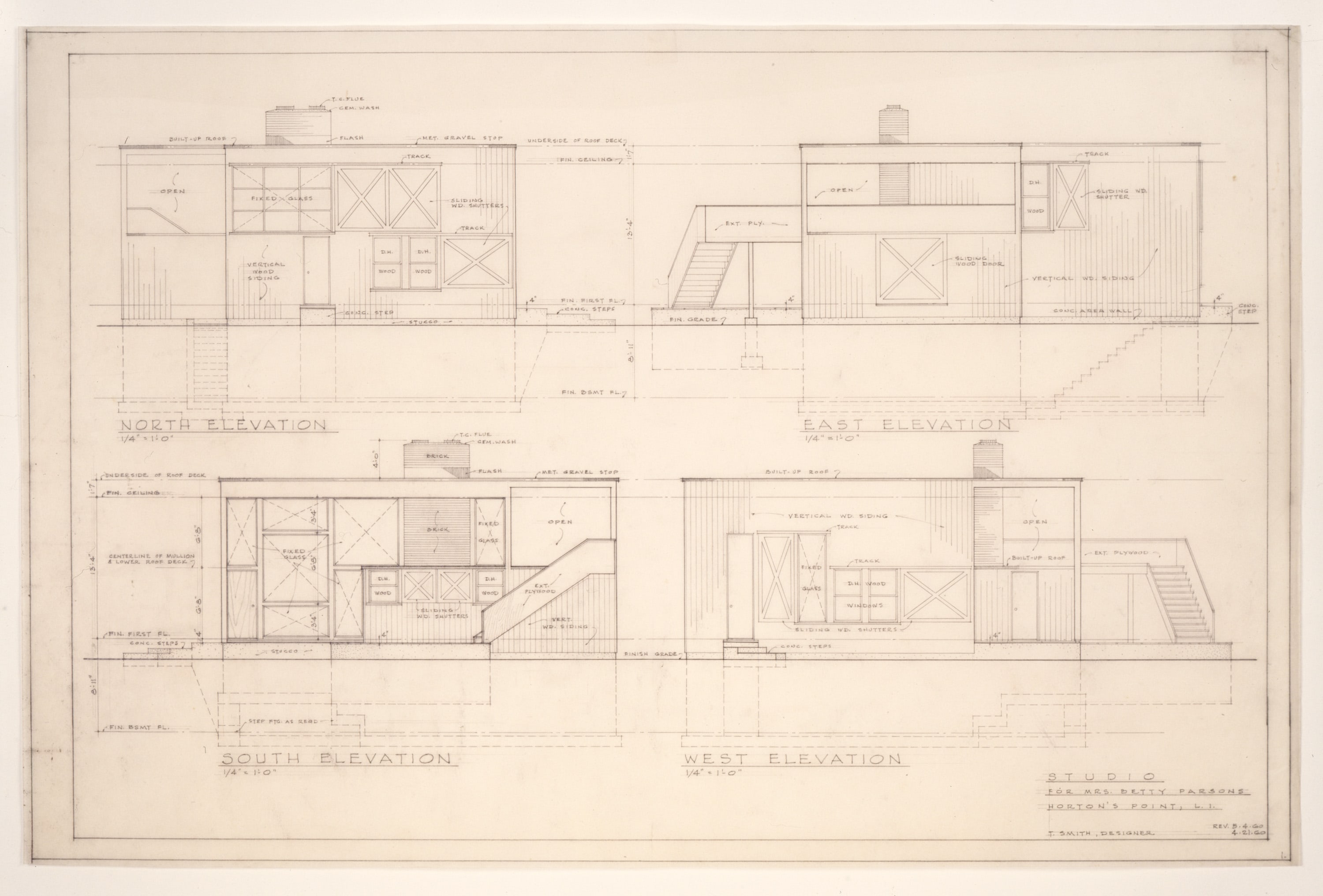

Smith’s architectural projects were relatively unknown to the public at the time, though a few received publicity because of the artworld clients who commission- ed them, and a handful of others have been subsequently studied. Some of the building projects originated from a circle of friends in the visual arts and theater scenes. In 1943, Smith married the opera singer and actress Jane Lawrence (née Brotherton) who was friends with the play- wright Tennessee Williams (1911–1983) and the artist Fritz Bultman (1919–1985). In fact, Smith’s immediate net- work included such luminaries as Hans Hofmann (1880–1966), Buffie Johnson (1912–2006), Barnett Newman (1905– 1970), Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Mark Rothko (1903–1970), Anne Ryan (1889–1954), and Clyfford Still (1904– 1980), among others. Smith built a painting studio in 1945 for Bultman in Provincetown, Massachusetts. In 1950, he collaborated with Pollock on an unrealized design for a Roman Catholic church. The next year, he designed and built a house for the painter Theodoros Stamos (1922– 1997) in East Marion, New York. In 1952, he designed and built a house for Orlando and Barbara Scoppettone in Irvington, New York, a kind of transitional design responsive to the topography and landscape while breaking with Usonian principles in his use of wood piers and glass. Around the same time, he began work on the above- mentioned house in Guilford, Connecticut, for the art collectors Fred and Florence Olsen, with spaces especially conceived to display their art collection, which included Pollock’s famous 1952 painting Blue Poles. He designed Newman’s solo exhibition at the gallery French & Co. in 1959, exhibitions for the Betty Parsons Gallery, and eventually a studio (1960) and guest house (1961–63) for the artist/gallerist Parsons—both in Southold, New York, on Long Island’s North Fork. (figs. 7–9) Indeed, Smith maintained a large network of close friends and colleagues, associations that provided him with a valuable outlet for experimentation and collaboration, leaving behind a rich body of architectural designs and urban planning projects—many of which have not been known to the public until now. In fact, Smith often reflected in writing on art, architecture, literature, and culture; yet his writing was not published. Instead, many of the published ideas we have by him are quotations from interviews.

Figure 7: Betty Parsons Studio, Southold, New York, 1960, exterior view, 1960s. Photo Ingeborg Tallarek. © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Figure 8: Betty Parsons Studio, Southold, New York, 1960, exterior view, 1993. Photo Andrew Bush. © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Figure 9: Betty Parsons Studio, Southold, New York, 1960. Elevations, graphite on paper, 19⅝ x 30. in. (49.8 x 76.8 cm). © Tony Smith Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Smith’s career is a study in shuttling among disciplines, an approach that feels distinctly contemporary today. His seemingly divergent experiments with forms and mediums were united by his organic, overarching investment in how individual elements may combine into a unified whole. Such sculptures as Moondog (1964), Smoke (1967), and Smug (1973), informed by his interests in spatial matrices, employ crystalline, lattice-like forms that confront the active spectator with a sense of dynamism as one moves around and under the arching, enveloping constructions. In these instances, Smith’s sculptures extend into architecture. Yet, these explorations and experimentations with space and volume originated in his early interest in architecture.

Our recently released architecture catalogue raisonné and the companion book Against Reason—like the preceding two volumes on Smith’s sculpture—intend to rethink the standard catalogue raisonné by embracing a broad range of contemporary scholarship and perspectives. The project innovates and updates what a large-scale, long-term research effort can look and feel like, better reflecting the evolving methodologies for integrating research, thinking, and writing—indeed, interweaving modern and contemporary art and design histories. This fresh approach is needed not only to fully grasp Tony Smith but to position his legacy—as a designer, artist, thinker, and visionary—in the contemporary arts and beyond. The catalogue raisonné volumes and companion books serve as an archival foundation for future study, interpretation, and analysis, pointing students, practitioners, researchers, and writers to the vast materials in the Tony Smith Archives related to his work and life. These books illuminate his ongoing vitality and relevance as they expand the canon of modernist thinking associated with the architect and the era in which he worked—with much still to explore.

Excerpted from Tony Smith Architecture Catalogue Raisonné Volume 2, edited by James Voorhies and Sarah Auld with authors John Keenen, Christopher Ketcham, and Cynthia Davidson. Reprinted by permission of MIT Press.