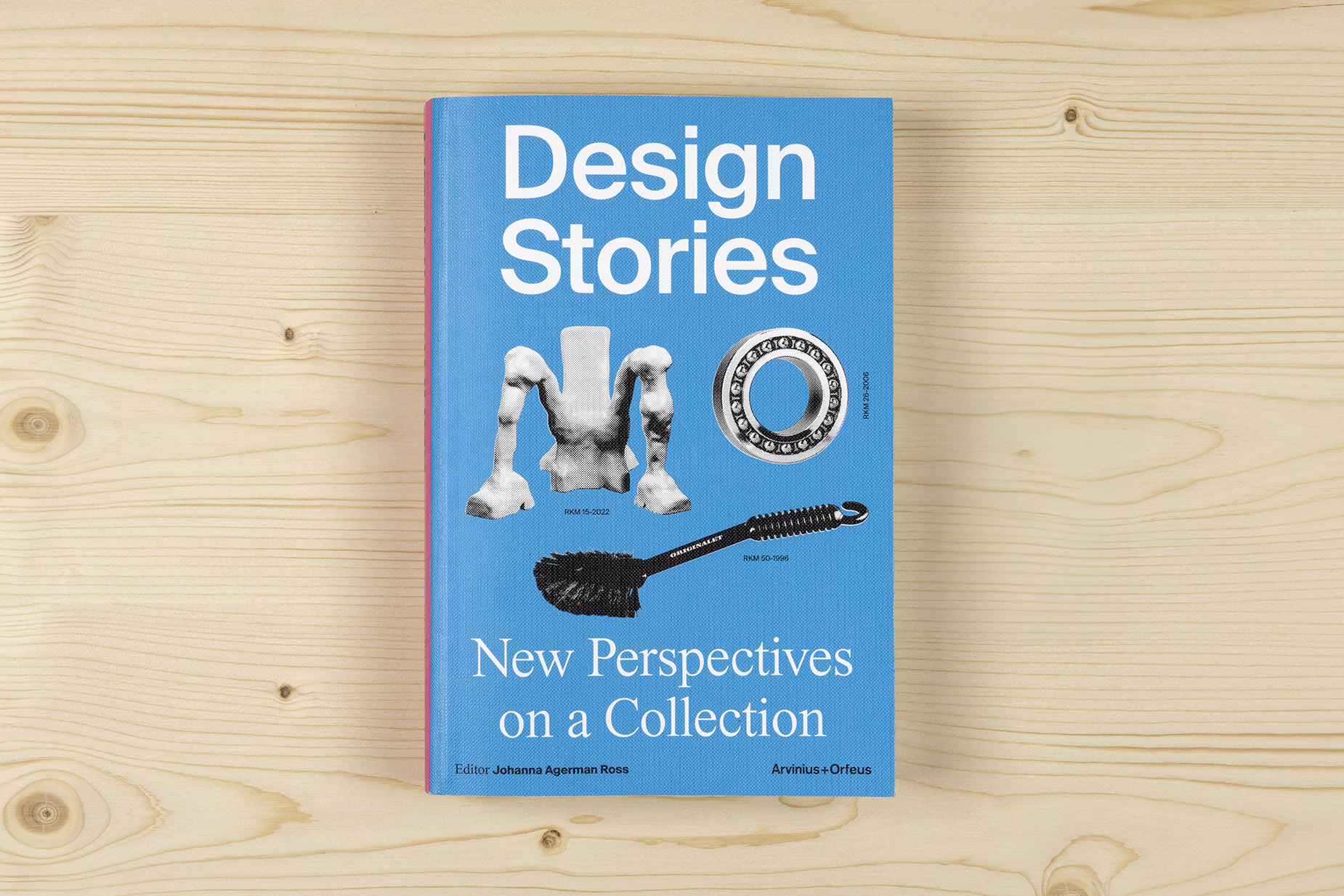

Design Stories: New Perspectives on a Collection catalogues a new permanent exhibition at the Röhsska Museum in Gothenburg, Sweden. In its introduction, Johanna Argerman Ross, the curator and editor, describes the book as a “continuation” of the thinking in the exhibition. There seems to be three core elements to that thinking. Firstly, that design is a discipline in flux, which means it is difficult to represent fairly in collections and exhibitions (think of the recent developments in “service design, social innovation and urban planning, along with an ever-expanding range of interdisciplinary collaborations”). Secondly, in line with other critical thinking about design today, the exhibition is concerned with how the museum’s collection of over 50,000 items of design, crafts, and fashion problematically reflects a mainly Eurocentric design history of the Global North. In the foreword, Nina Due, director of the museum, writes: “little consideration […] has been given to minorities, Indigenous peoples, and their histories”. Lastly, the exhibition provokes thoughts on how the museum’s collection is limited to offering a traditionally Western (read: capitalist) perspective on what design is. That is to say, valuable design is assumed to be something that “shapes things to make them easier to use and manufacture, to make them more attractive to consumers, and to add status and create value”. This means that the collection underplays design’s capacity to “protest injustices, as well as to criticise or comment on the prevailing social order”. As such, with focus on the last 150 years of design, Design Stories asks “[w]hat is design, and how can a design museum address this question through its collection?”

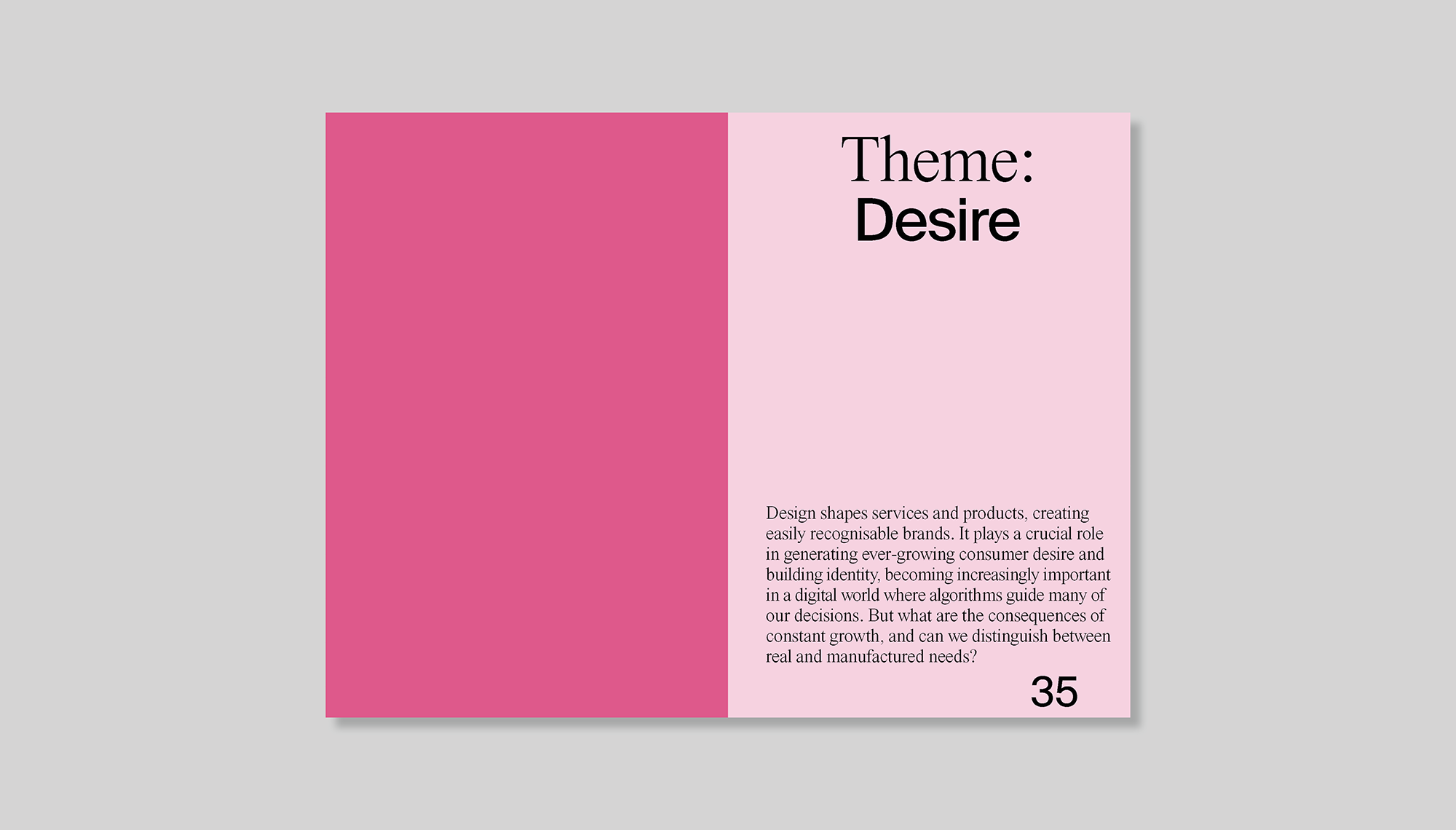

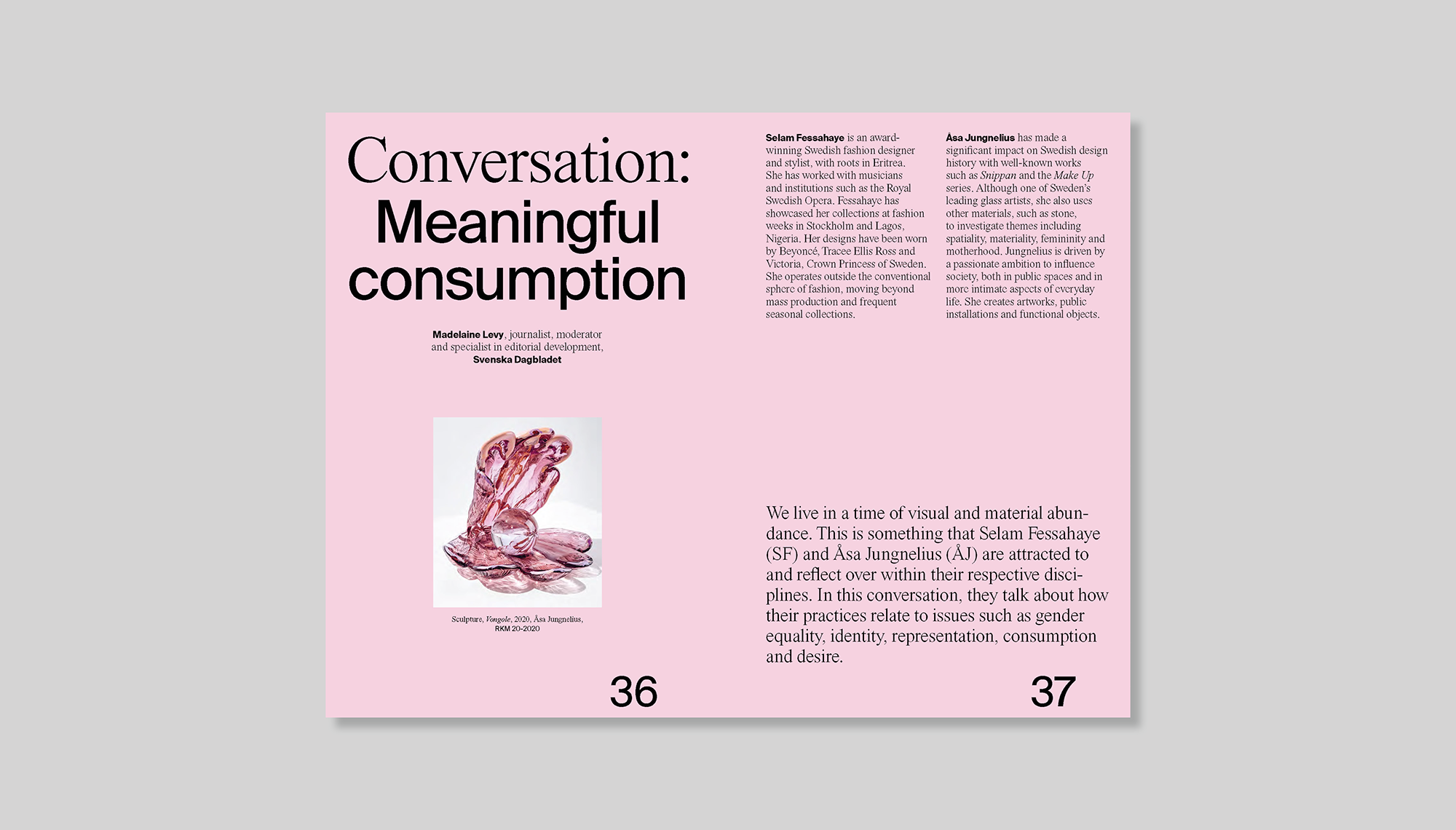

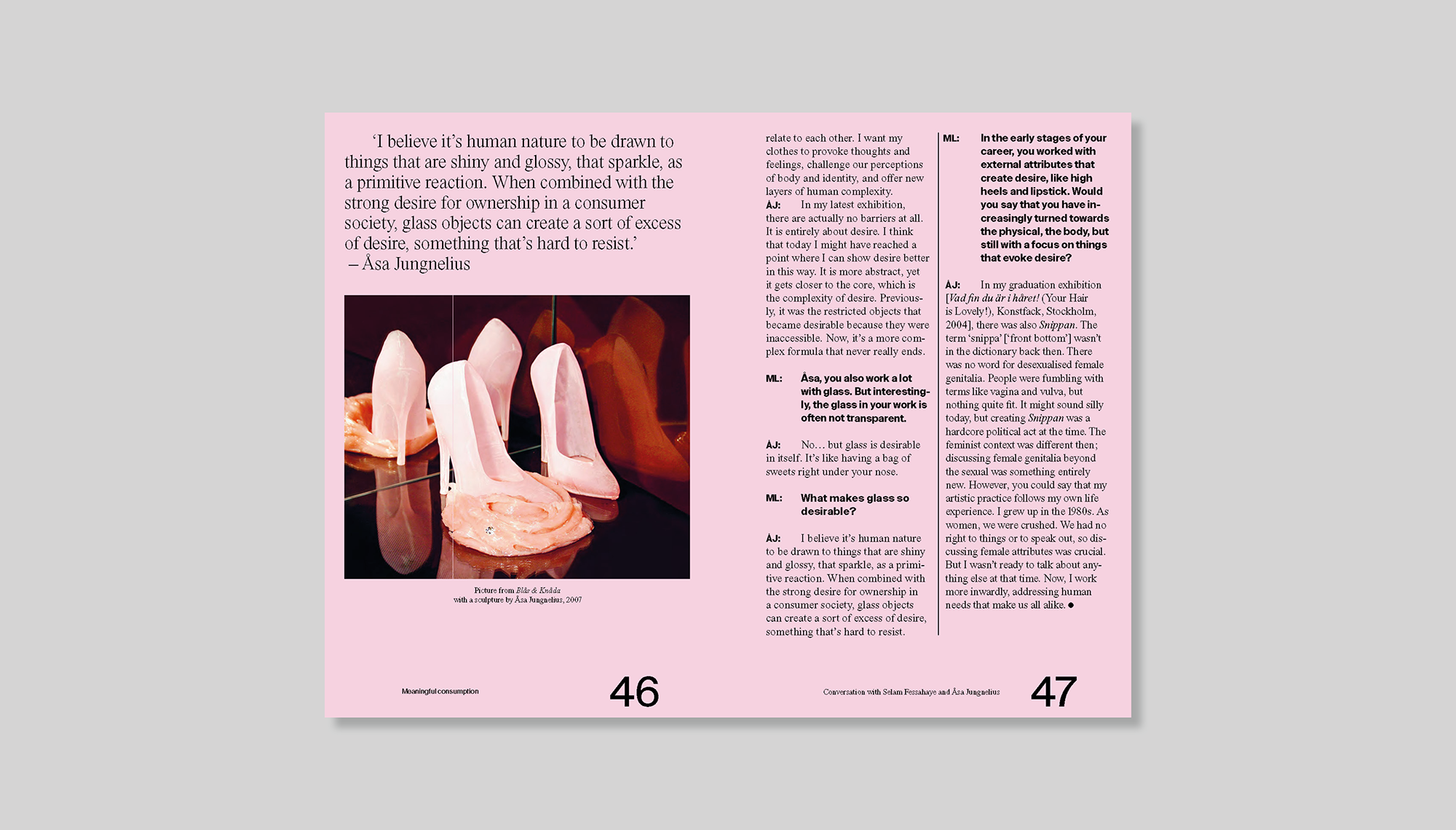

The bulk of the book is split into six themes: Desire, Innovation, Creativity, Efficiency, Change, Belonging. Each theme is made up of three parts. First is a conversational interview with designers and artists working in contexts loosely associated with the theme — a designer and a CEO for “efficiency”, a fashion designer and a glass artist for “desire”, and so on. They read as light, pop design journalism offering just enough insight to get beneath the surface of the works without too much confounding detail or jargon. This is followed by a set of full-bleed, bright and bold photographs capturing the theme “outside of the museum’s walls”. Closing each theme is a short essay that tends to be theme-adjacent rather than head-on critical takes on the theme itself. For instance, under the theme of “innovation” John Redström writes about the problematic importance of machines in design’s history, and under the theme of “efficiency” Thomas Cubbin questions the assumed role of the designer as “optimiser”. Further distinguishing the changes of themes are the pastel-coloured paper stocks, a different one for each theme. The photographs, which are sandwiched in the middle of each pastel block, are printed on contrasting magazine-weight glossy paper. Along with its heft, these editorial designs make the book feel like a well organised, contemporary collection of diverse materials put together for readers interested in the contemporary challenges of curating design, crafts and fashion today.

The themes are an alternative “multifaceted approach” to the more traditional “linear narratives”. The latter tend to leapfrog chronologically from icon to icon without straying from the established canon of design history. As such, presenting works (predominantly by designers working in Nordic countries) under the umbrella of a “theme” enables a more explorative sprawl in the conversations and essays. More than that, it also invites the reader to find their own point of view to be a worthwhile contribution when thinking about what design is today. Rather than being a distant and passive observer, for the assiduous reader, Design Stories displays design’s histories and present definitions as something lively and participatory. Also supporting this activation of the reader are a series of rhetorical questions in the introduction to each theme: “[W]hat are the consequences of constant growth, and can we distinguish between real and manufactured needs” (Desire). “[H]ow can a designer articulate their creative journey?” (Creativity). “[H]ow can engagement be transformed into a questioning and critical practice?” (Change).

Aesthetically furthering the importance of one’s independent perspective — particularly as a mode of criticising the established histories of design and assumptions of its value — are the photographs taken by Lars Brønseth. At first they might register as an eccentric splash breaking up the text-heavy conversations and essays, but they are doing more than window dressing. The photographs are well-made snapshots. The scenes aren’t stiff and the compositions aren’t contrived; in a non-pejorative way they look naïve and amateurish because they are not taking on the controlled, elevated language of archival photography. Instead, Brønseth is snatching at design as something unfixed, and that requires him to strike a particular and literal point of view to capture that fleeting thing. Overreading Brønseth’s photographs, the limit of what his position can reveal (or: know) is amplified by the deep, blown out shadows made by the on-camera flash. This exaggerates the blind spots of his perspective, which is to say: his photographs are just one of many ways of viewing the same design. Brønseth likely represents the ideal reader of Design Stories because he seems instinctively interested in the stories it’s possible to make with designs at each unique encounter rather than being invested in the official “received” narrative, so to speak.

This multivalent appreciation of design is articulated most clearly in the last part of the book in a collection of “Object Stories”, in which a modest selection of designs from the Design Stories exhibition are written about by a series of guest authors. They read like extended exhibition labels or wall texts and are written in a dynamic range of styles. Some of them focus more on cultural context, like Frida Lundmark’s text on the 2003 BabyBjörn baby carrier orOlivia Berkowicz’s text on Ewan Nowak’s 2024 Incognito jewelry. Others are more like traditional designer profiles, such as Brigitta Martinius’ text on Bruno Mathsson’s 1934 Modell 34 recliner chair and Oscar Vilhelmsson’s text on Astrid Sampe’s 1970 computer colonne. These Object Stories are individualistic and at times modestly personal. To further highlight this range of approaches to design, it would have been interesting to read multiple authors writing on a single object, something like Sophie Calle’s Take Care of Yourself. Imagine what knotted and contradictory stories a technician, a lecturer, and a creative director might write about Kenneth Österlin’s 1990 Signal box design, for instance.

Considering the way Design Stories is interested in multiplicity and divergence, it is odd that each of the Object Stories’ texts have been written by “people that are, or at some point have been, working at or with the Röhsska Museum”. The result is that much of what’s written — perhaps only with the exception of Michael S. Bekele’s text on the process of creating masks — shares a similar designerly cadence. This is not in itself a problem but it risks the reader losing the responsibility to suspend their expectations of what “proper” design is: fundamental, Eurocentric, commercially oriented. As such, the designs and their journo-critical commentary are so proficient and familiar (read cynically: predictable) it risks undercutting the labour of a reader’s imagination which is needed if the motivation of the book is to develop new empathic bonds to design for funders, acquirers, collectors, curators, and the larger public.

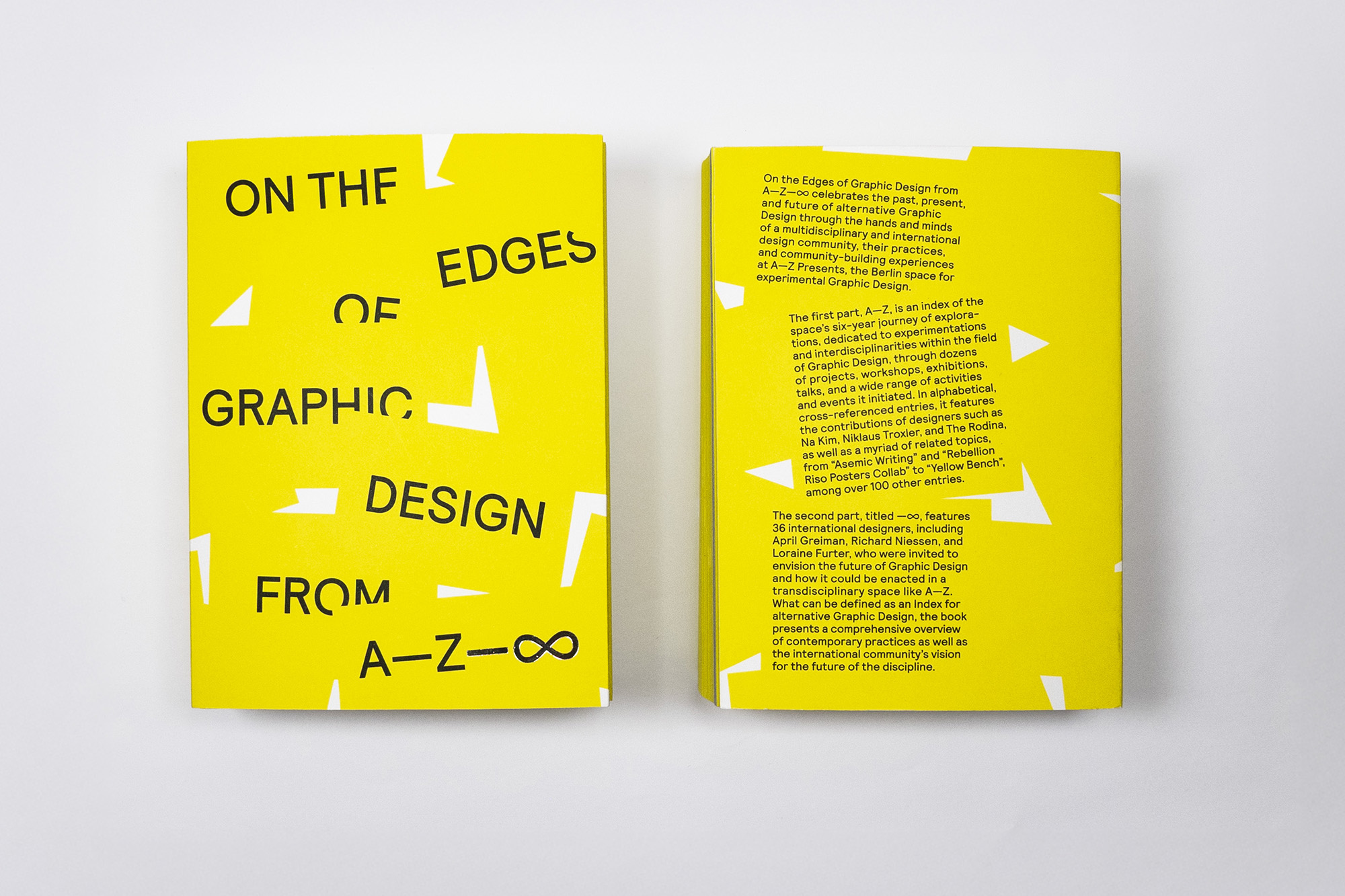

Recent other books that ask similar questions of design’s contemporary culture — albeit not with the same specific focus on collection and curation — offer voices that are frustrated and thankful for a platform (Who can afford to be critical?) they make energetic attempts to collaboratively deform design into something less-easy to grasp (Glossary of Undisciplined Design) or they are playful with the editorial expression of design’s histories (Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought). Design Stories, instead, reads as well tempered and well known. The effect is that, from page to page, there never feels to be any friction, conflict, force, jeopardy. For instance, by skirting the polemical nuances of design’s decolonization — an inherently problematic issue of contemporary design — Design Stories has managed to present something that in recent years has been called transformative, radical and urgent in an unusually casual way. As such, the book probably works best as an extension of the exhibition more than it does as an expanded, meta-critical discourse about the themes and motivations of the exhibition itself.

To be clear, Design Stories is not a shallow or insincere book, it is the result of years of research and hard work and it has legitimate contemporary currency. Whilst it doesn’t present itself as a critical reader on design-cultural theory, it still treads close to many of its related complex topics. As such, some readers might expect more clear signposting to existing publications in a more deliberate, long-form way than the list of references given at the end of the book. For instance, by presenting works thematically in the way they have, Design Stories is able to provoke thoughts about representations of genders, classes, and ethnicities without making them exclusive categories to distinguish or evaluate the design works themselves. Commendably, in this way, “Otherness” is saved from being a quality worth “acquiring” and “collecting”. In other words, icons of tradition are not being replaced with trophies of difference. However, those categories are still left unprovoked and unquestioned despite there being appended references to Reina Lewis and Nancy Micklewright’s Gender, Modernity and Liberty, Edward Said’s Orientalism, and Judith Butler’s Categories by which we try to live. Ultimately, guiding a reader to inform their own stories about design would be a way to strengthen a reader’s understanding about what design is today and why (not only how) it should be represented in a museum’s collection.

Design Stories will certainly appeal to a broad readership but it is likely that curators and those interested in contemporary Nordic design will find this book most valuable. Whilst the interviews offer candid insights and the essays offer an eclectic mix of thinking about design, undoubtedly, the most engaging part of the book are the Object Stories. They are quick, pithy, not overly commanding of the designs; they read like spontaneous, passionate experiments. Greedily, I wanted many more of them. We need new ways to think about design today. Writing new, alternative, counter histories is one text-laden and generally independent way of doing it. But to think long-term about the acquisition, collection and narrativization of design in the way that Design Stories does requires the ambitious support of many stakeholders, it demands collective creative agency. It might be hopeful, but it would be meaningful to see similar work happening at smaller, regional levels too. If it did, Design Stories would be an invaluable companion.