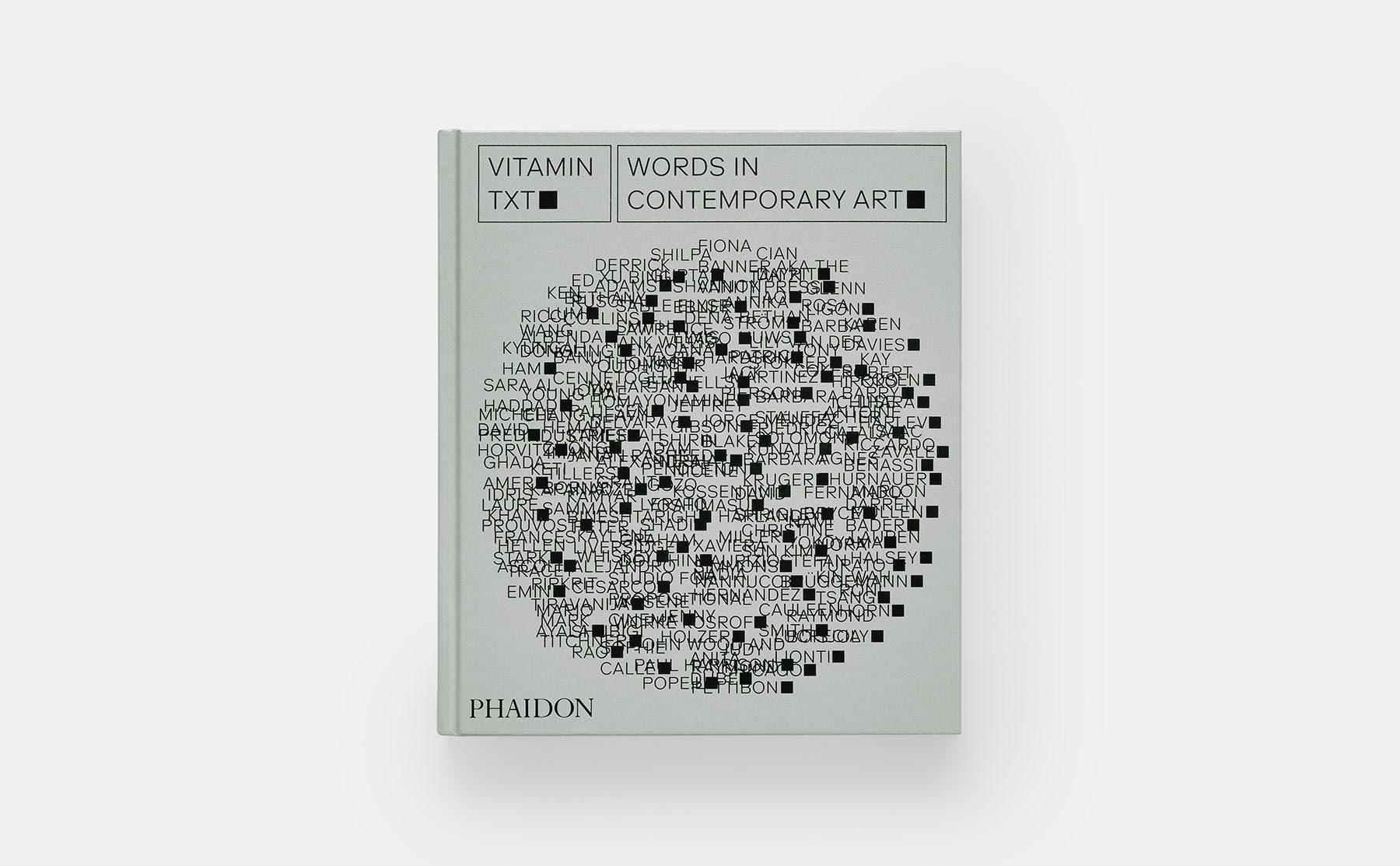

Phaidon’s Vitamin series has been running for over twenty years. Its eleven titles have focuses ranging from mediums such as clay, ceramics, thread and textiles to material processes like collage and drawing. The latest title, Vitamin Txt: Words in Contemporary Art is a global survey of over one hundred contemporary artists that use text in their works, chosen by a panel of industry nominators—a variable mix of collectors, writers, curators, critics, directors, and historians. There are instances of text used to evoke the slipperiness of language, text pulled from everyday street-level places, text to express the poetically ambiguous, text as a “bombardment of language”, and so on.

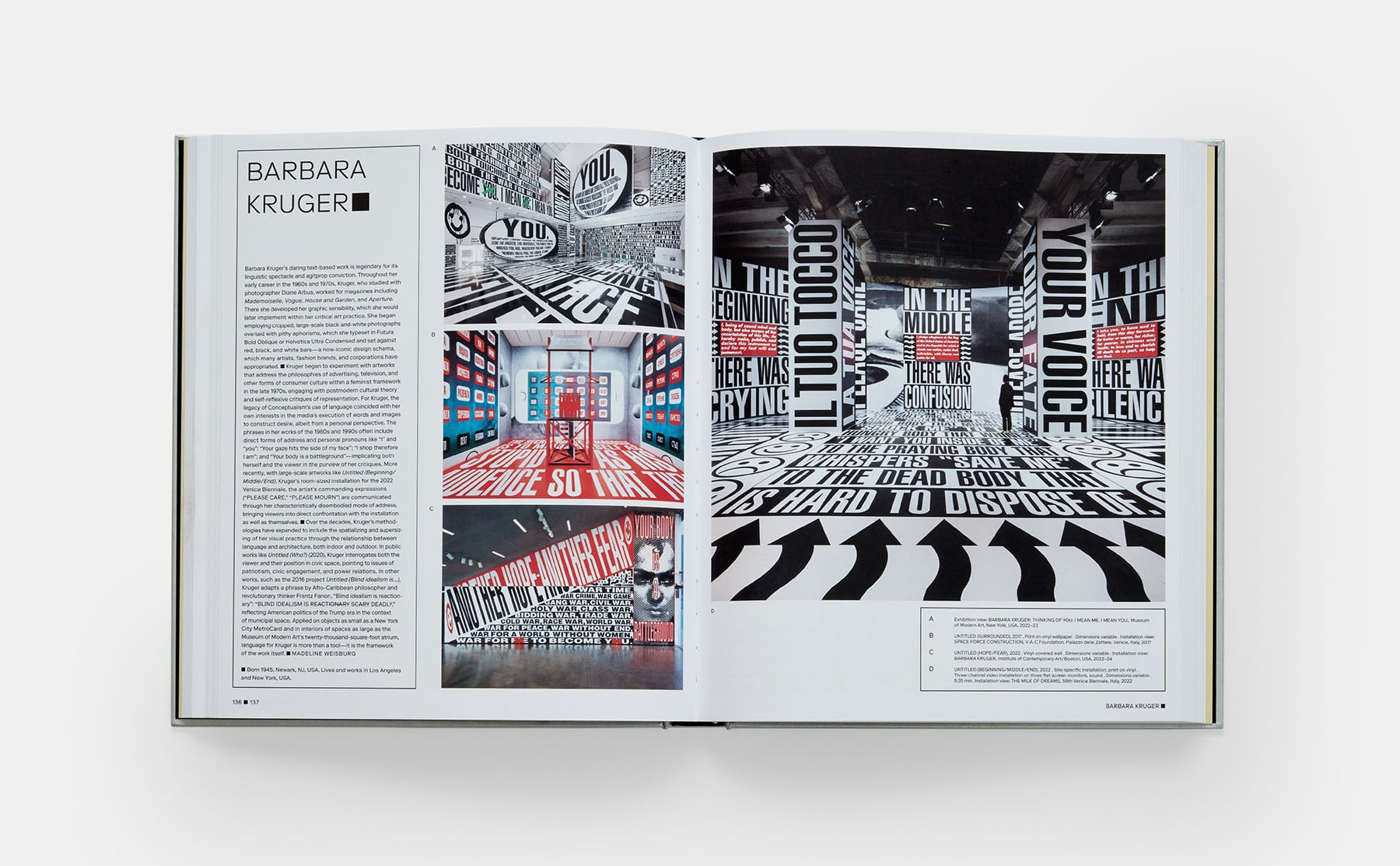

Accompanying each nominated artist and the select images of their works is a clipped introduction. Generally, this is written without relying on the common anchorage of biographical details and instead focuses specifically on contextualising the artist’s works in relation to the theme of the book. Too infrequently, though, these well tempered descriptions give language to the works that enable them to grow out, spore-like, and connect with other artists featured in the book as well as to other, seemingly-oblique works of criticism, philosophy, poetry, and fiction. These brief but insightful introductions are written by an array of writers that are as diverse as the artists they write about. If the writers are germinating the roots necessary to contextualise the artworks then the nominators could be said to give far-reaching, tendril breadth to the theme of text in contemporary art—and this is all achieved in a sober, dependable (very Phaidon-like) way.

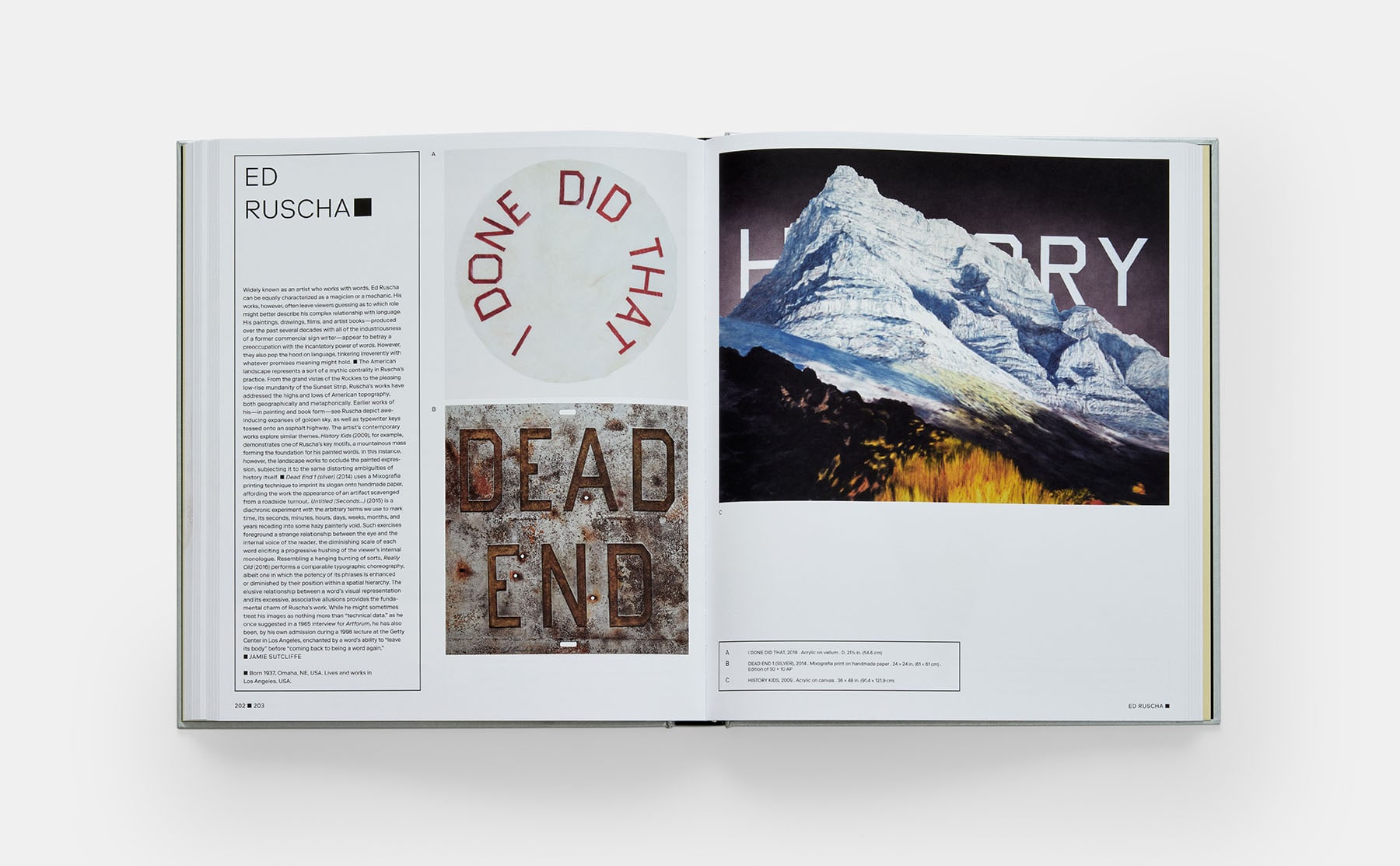

The artists are organised alphabetically, which is a familiar way to order miscellaneous stuff like this; whilst it avoids any sense that there is a pre-existing coherency to the book’s theme it also undercuts the potential for other, perhaps less-obvious, ways of navigating this nascent focus. For instance, there could also have been an option to navigate the works by geolocation, date of completion, materials, processes, aesthetic styles, and so on. These are all just as equally arbitrary categories but if included in addition to alphabetisation they could sharpen bleary eyes and offer unimagined paths through the thicket of works. Like all reference books, there is a certain monotony once the works are set in their tracks and the reader passes by work after work and on and on. That being said, because it is such a hefty hardback, Vitamin Txt is not something that can be casually, or speedily, thumbed through. The size of the pages means they fan slowly and with each spread dedicated to a different artist there is a density to everything that peels past on first scan. As such, it is a book to return to; to be pushed around studio desks and stacked on coffee tables.

Evan Moffitt, writer and digital editor at BUTT magazine, introduces this volume of Vitamin with pellucid clarity. He manages to convincingly shepherd an unwieldy collection of works into a flock of activity that resembles a coherent form. Whilst giving a degree of socio-cultural contextualisation to text in contemporary art, Moffitt’s introduction reads as primarily concerned with two focuses. Firstly, teasing out the historical endurance of text in art—this could be read almost as a varicose history that runs, for the most part, alongside the history of typography and graphic design. Secondly, perhaps with awkward conviction, Moffitt is explaining why it is necessary to render text in art visible now. He does this by inflating a swell of contemporary urgency related, in part, to how the internet “has transformed the way we read and look at art” and thus creates “new imperatives” for artists to make work capable of translation across multiple media (and mediums). Moffitt closes with: “The future promises many more devices”. The urgency of the book’s theme might not be very convincing, but it also doesn’t need to be for this book to be worthwhile.

There is a genuine enthusiasm in Moffitt’s introduction and it is well worth returning to whilst passing through the artworks. The contrasting yellow page colour of the introduction—compared to the off-white pages of the rest of the book—is reminiscent of an American-style yellow jotter pad; it gives the intro a sense of a sketch, a work in progress, a series of ideas raw but nonetheless written. This also complements the overall tone of Vitamin Txt, which reads like a point of departure more than it does a terminal end; it offers text in contemporary art as a resource for the reader rather than as a thematic territory of art that is cloistered in its pages.

It is unusual, though, that design is not considered to have a stake in this project. It wouldn’t be a strain to imagine a sizable readership of Vitamin Txt being graphic designers. Despite this, the nominators of the artworks, for instance, include collectors, writers, curators, critics, historians but not graphic designers or design writers and critics. I am not wanting to revise Rick Poynor’s Art’s Little Brother argument from 2005, but the lack of consideration of typography specifically, or of graphic design more generally, is a peculiar omission. In fact, the way that Moffitt defines an artist is not too dissimilar to how some designers might also think of themselves: “a maker of worlds, an assembler of forms and content, a diviner who writes things—with or without words—into being”.

Perhaps, I am knocking on an open door to say that Vitamin Txt relates to graphic design and therefore could have sought insights from nominators or writers in design. That being said, undoubtedly, from the vantage of art, the selection of works included in Vitamin Txt has a far greater reach than what could be expected from a more traditionally punctilious designer’s-eye. As such, for a graphic designer interested in text (or, let’s just say: typography) Vitamin Txt is an excellent way to see their passion through more naive eyes. That is to say, from a perspective that is not crowded by the heritage of designerly, technical know-how.

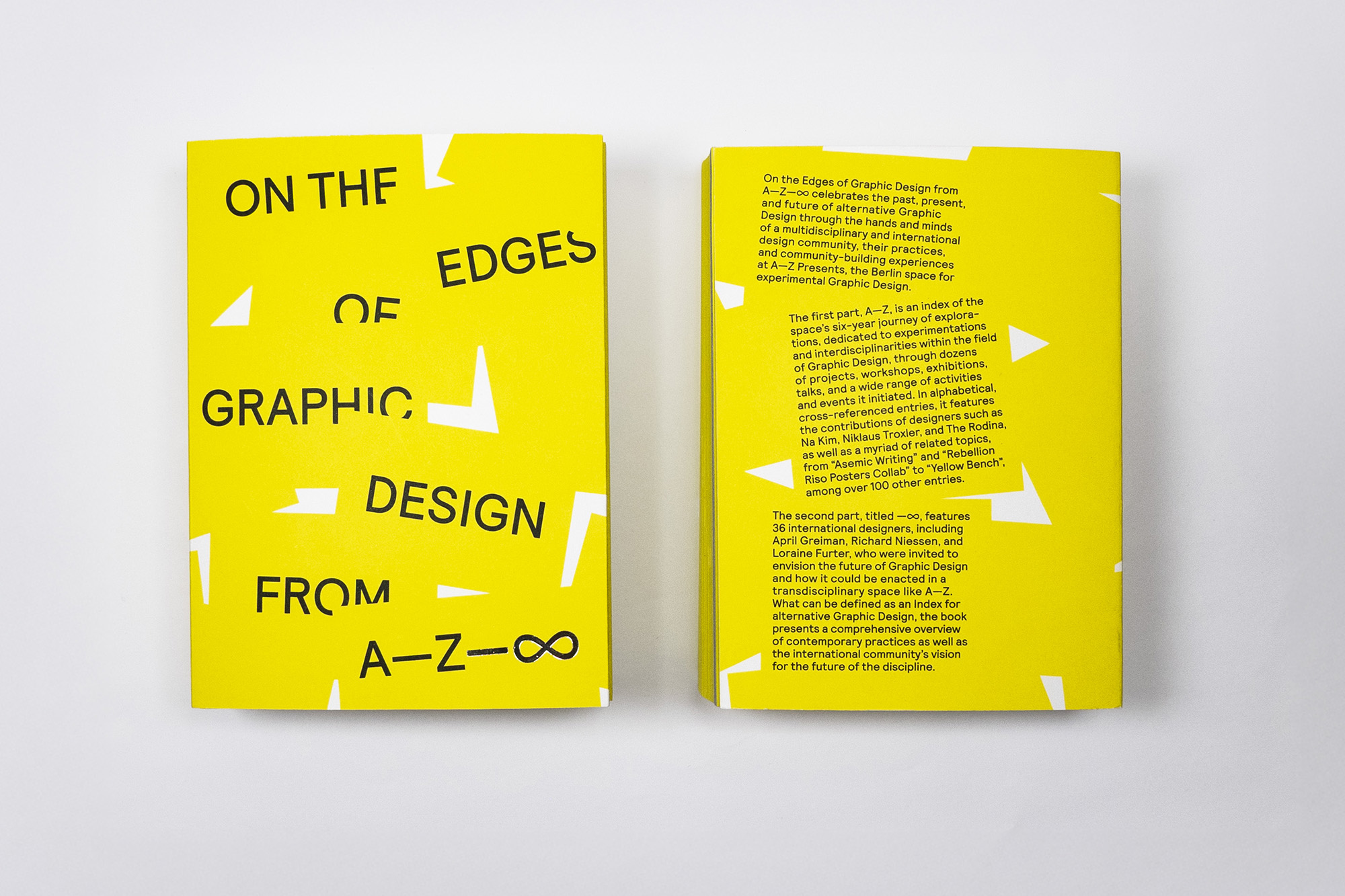

Vitamin Txt could easily be considered material to feed the increasing appetites for non-formalist and anti-canonical histories of graphic design—think: Feminist Designer, Fracture, and Thinking through Graphic Design History to name a few. As such, perhaps what makes Vitamin Txt a curious read for the more critically-oriented design readership is actually that “omission” of design in the first place. The challenge for such a reader, though, would be the need to think this collection of art works into new histories of graphic design. This is certainly the contemporary currency, and incidental urgency, of Vitamin Txt to a design readership. To clumsily snatch the closing line from Aggie Toppins’ article calling for such new graphic design histories: “What we gain from diverse approaches, including history beyond the profession, are new ways to envision designing now and in the future.”