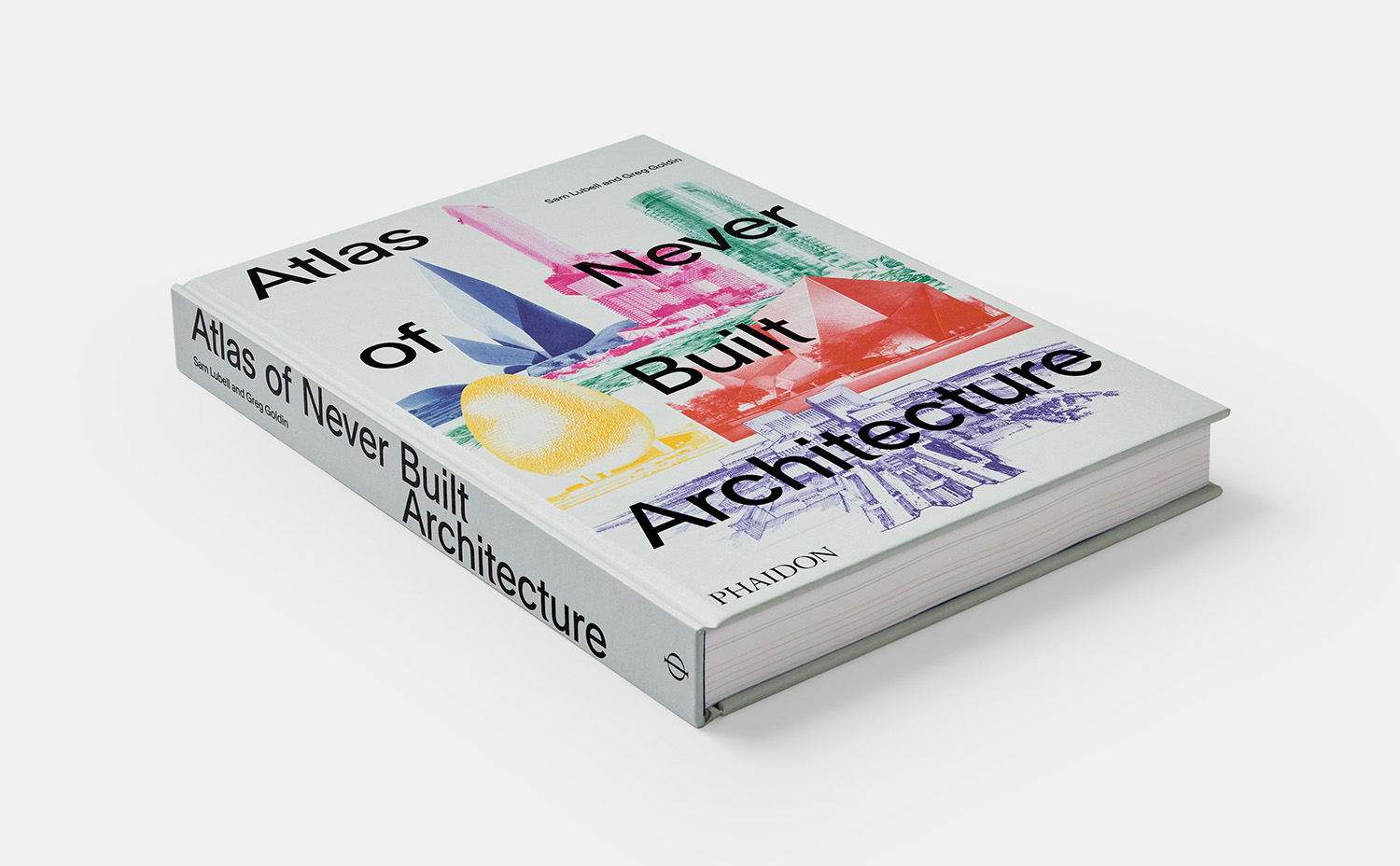

The alternate universe of failed architecture proposals showcased in our Phaidon Atlas of Never Built Architecture spans more than 70 countries and 120 years. While you might first be intrigued by its beautiful, often bizarre images, the book, more importantly, offers endless stories, lessons, and inspiration. It’s filled with compelling concepts that could still prove useful. It puts into sharper focus the factors that can sink architecture, from finances and politics to internal squabbles, deception, and bad luck. It reminds us that ideas don’t die even when buildings do. And it introduces us to a roster of talented architects and designers that may have hit the limelight if only that one undertaking had gotten off the drawing board.

It also dazzles us with the gorgeously rendered world of the visionary. The pure universe where architects can push boundaries—aesthetic, structural, social—without being held back by messy, boring reality. Below are some examples. While none were realized, most reflect an abiding drive for bigger, better, more ambitious, more radical. (What the results would have been, is, of course, impossible to know.) Many still resonate today.

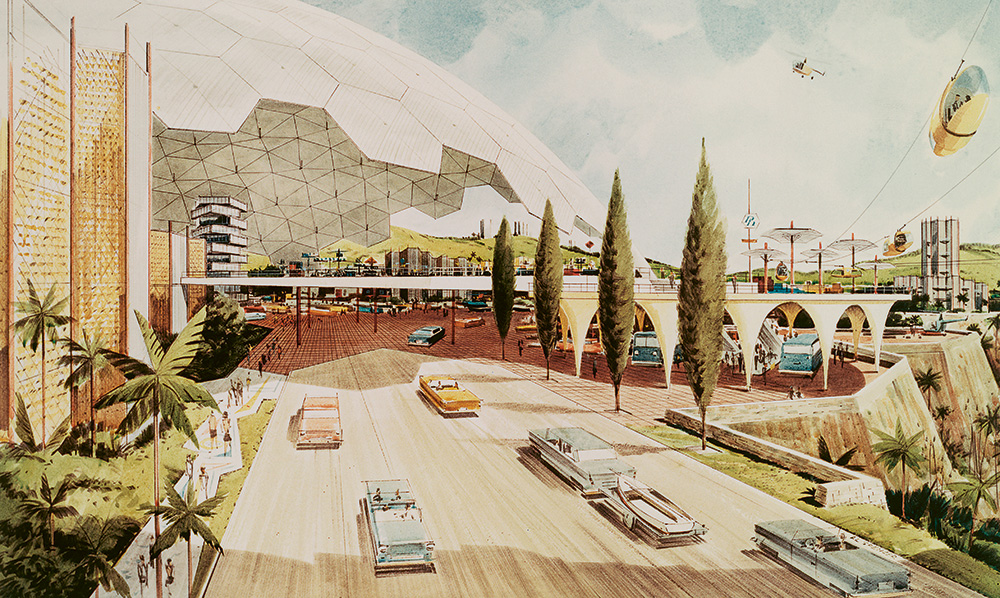

Port Holiday, Smith and Williams, Lake Mead, Nevada, 1963

Whitney Smith and Wayne R. Williams helped invent the vocabulary of everyday modern architecture in post-war Los Angeles. In 1963 J. Carlton Adair, a bit-part actor, casino promoter and Las Vegas land speculator who owned swathes of land around Nevada’s Lake Mead, asked Smith and Williams to lend visual panache to his years-long scheme to develop his holdings into a township that he called Port Holiday.

Smith and Williams’ rendition of Adair’s dream had it all: a geodesic dome, an aerial tramway and a Modernist version of a castellated chateau. All was infused with the zippy flair that reflected the optimism of early 1960s plans to turn deserts into oases and convert barren land into multimillion acreage.

Local and state officials endorsed Adair’s $320 million plan, which involved an artificial lake with 13 miles of shoreline, resort hotels, an eighteen-hole golf course, floating homes and a zoo. Over several years he attracted a series of corporate backers, from Boise Cascade Home & Land Co. to Gulf Oil and General Electric. He overreached himself, however, eventually declaring bankruptcy in 1972, with just $200 in the newly named ‘Lake Adair’ company’s coffers. Adair’s vision was eventually given life, albeit lacking the spirit of Modernism. In 1991 a lake was created, known today as Lake Las Vegas, surrounded by Tuscan stucco luxury homes.

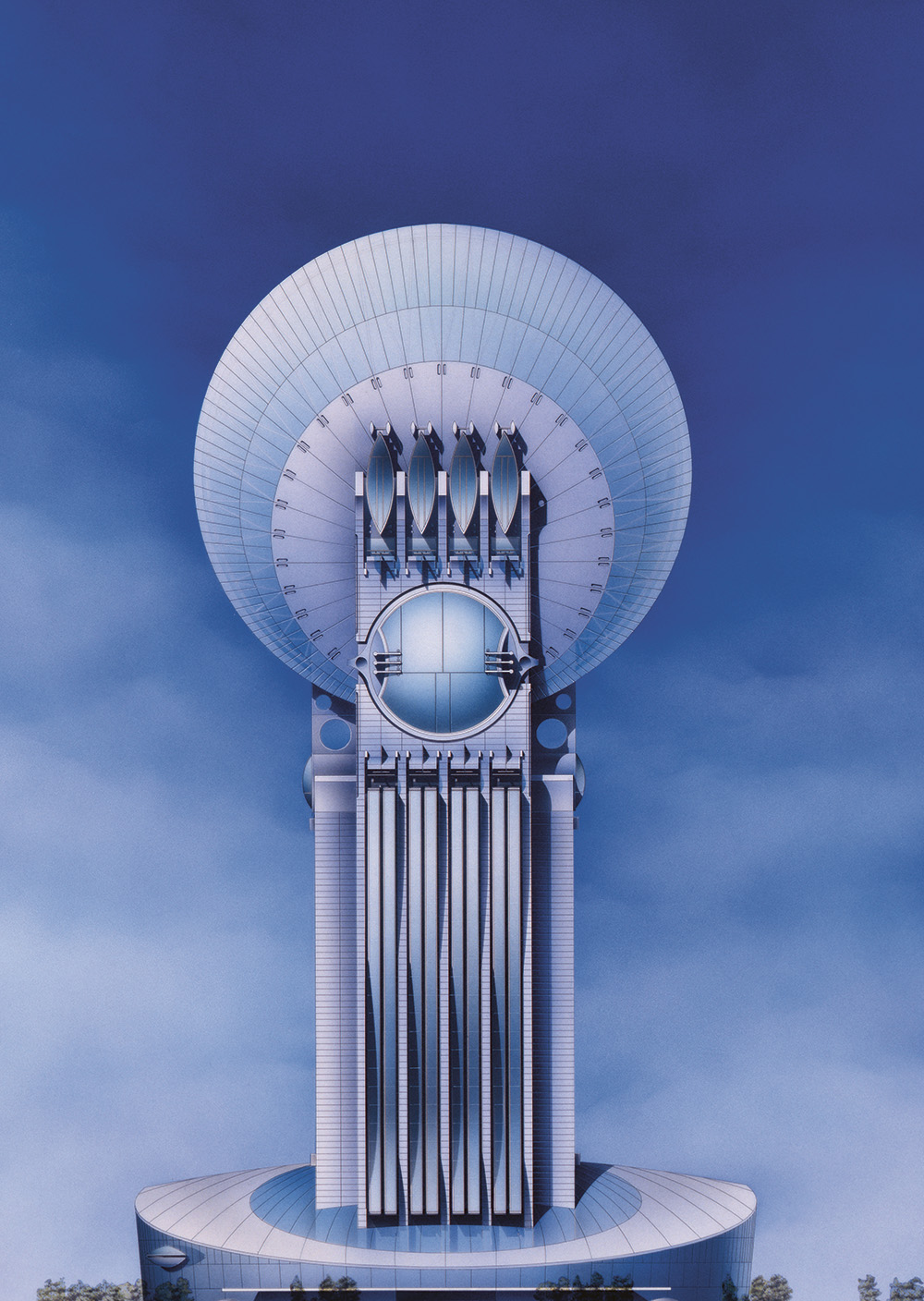

Moon Tower, Shin Takamatsu, Osaka, Japan, 1987

Few architects have lived up to the ‘more is more’ spirit of postmodernism like Shin Takamatsu, whose outrageously expressive designs (many of them actually built) take inspiration from the spiritual, cosmic, futuristic and industrial. ‘I am an old-school architect,’ he once said. ‘Always dreaming of architecture as a monument or as something with a symbolic presence.’

In 1995 Takamatsu entered a competition to develop a centerpiece for Rinku Town, a new commercial development on reclaimed land adjacent to Kansai International Airport in the Osaka suburb of Izumisano. Takamatsu’s Moon Tower, thirty-five stories and 651 feet tall, accommodated a 300-room hotel, shops, a large casino, and a museum of the work of the French visionary artist Gérard Di-Maccio. It was topped by a shining, convex moon 295 feet in diameter. The reinforced-concrete building’s shaft was clad in glass with vertical textured lines and solid edges, offsetting the floating character of the shell-like “moon,” wedged between two “jaws” containing the museum: a crystalline hall showcasing Di-Maccio’s masterpiece, the massive oil painting Grande Toile (1997), on the ceiling. Under the museum a hemispherical glass dome contained an otherworldly restaurant inspired by the artist’s work.

In the end, the competition stalled and was never implemented. The Di-Maccio museum eventually opened in 2010 in the tiny town of Niikappu, in the far north of Japan.

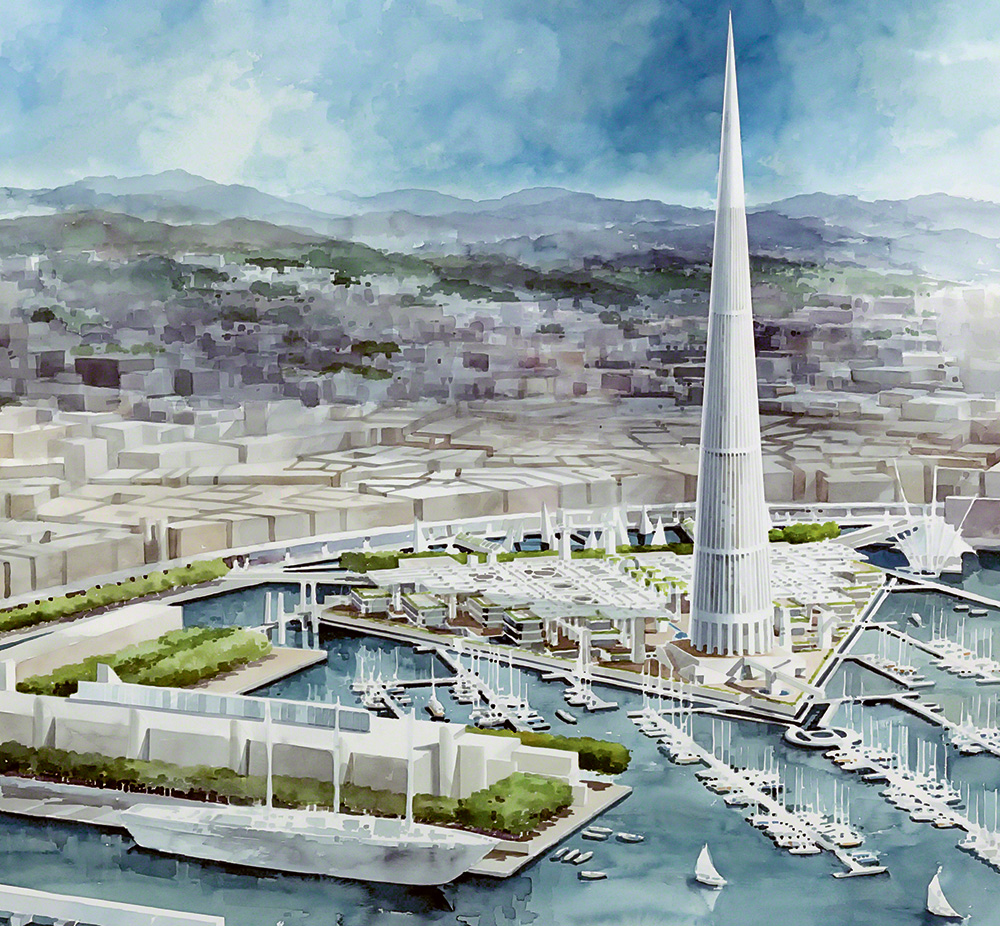

Il Porto Vecchio, John Portman, Genoa, Italy, 1988

John Portman elevated the idea of hotel lobby from regal parlor to galactic extravaganza. For Genoa’s anticipated celebration of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s departure from his home city to the New World, Portman turned his showmanship inside out. He proposed installing a triangular island in the city’s historic harbor, with a raised plaza shaded by a gridded concrete sunscreen— a nod to the medieval arcades of the city. There was also an undersea aquarium, with sail-shaped roof lights poking through the water’s surface. He intended to remove the highway cutting off the seashore from the row of twelfth-century buildings whose porticos once stood at the water’s edge.

But the showstopper was a conical tower, sheathed in white Carrara marble, rising 843 feet above the plaza. It would be the tallest tower in Europe. A ring of splayed columns at the base created a loggia opening onto a bank of elevators to speed people to the observation deck thirty-three floors above the boats bobbing in the harbor. The pencil-point tower was meant to “give Genoa a visual identity, like the Eiffel Tower does to Paris or the Sydney Opera House does to Australia,” Portman said when the project was unveiled.

His plan was welcomed by some local press, but harshly dismissed by others as ‘retrograde’, and never won official approval. A different harbor aquarium, by Renzo Piano, opened in time for the Columbus quincentenary.

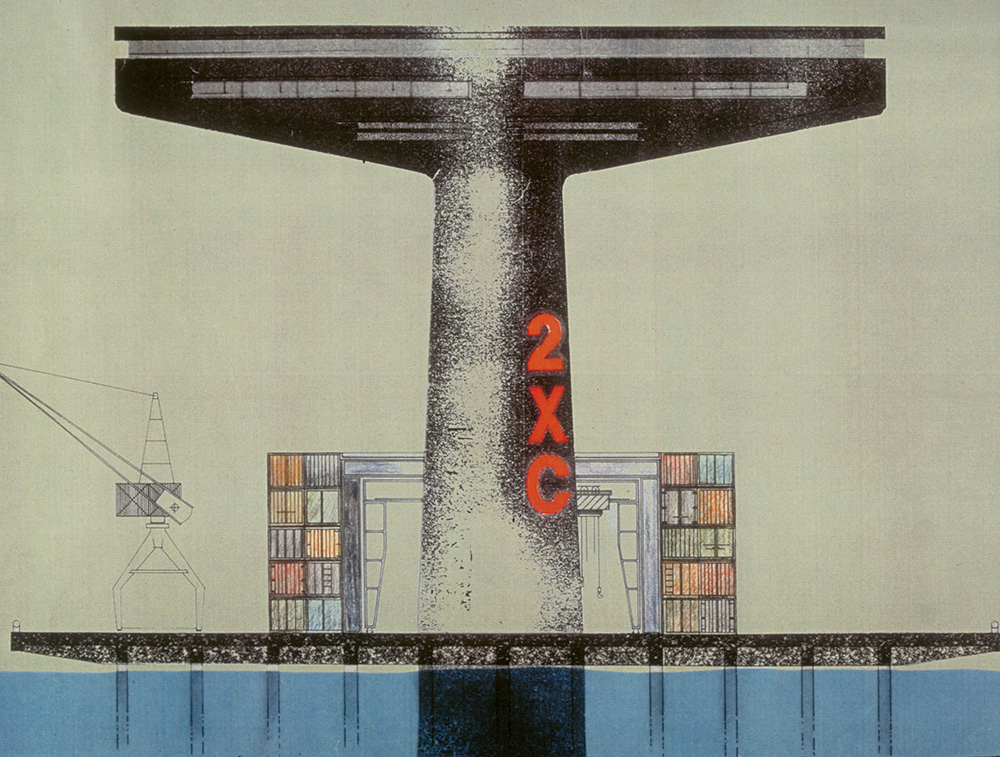

World Harbour Centre, Jean Nouvel, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1989.

Aptly called “The Tail of the Whale,” this colossal black object was commissioned by the Port of Rotterdam, which wanted to draw tourists to land’s end, at the North Sea. Maasvlakte, the vast, flat area of the port created in the 1960s by reclaiming land from the sea, itself lacks all scale. Massive ships, hulking steel containers, and otherworldly cranes undermine any sense of proportion. Little wonder, then, that Nouvel sketched something that looked unknowable, standing in an ocean of outsized objects.

The harbour centre had two distinct parts. An exhibition hall was to be built of discarded containers, “a bit rusty, stacked up,” Nouvel said. One would enter through hangar doors, then pass through to the end of the dock, to a platform at the edge of the water. That’s where the ‘tail’ of the whale was to be, a hollow steel sculpture as tall as a crane. From a crow’s nest high up inside the whale fins, one would have a bird’s-eye panorama of the port and the North Sea. In 2021, with no whale in sight, the port commissioned another architect to build a landmark for the port.

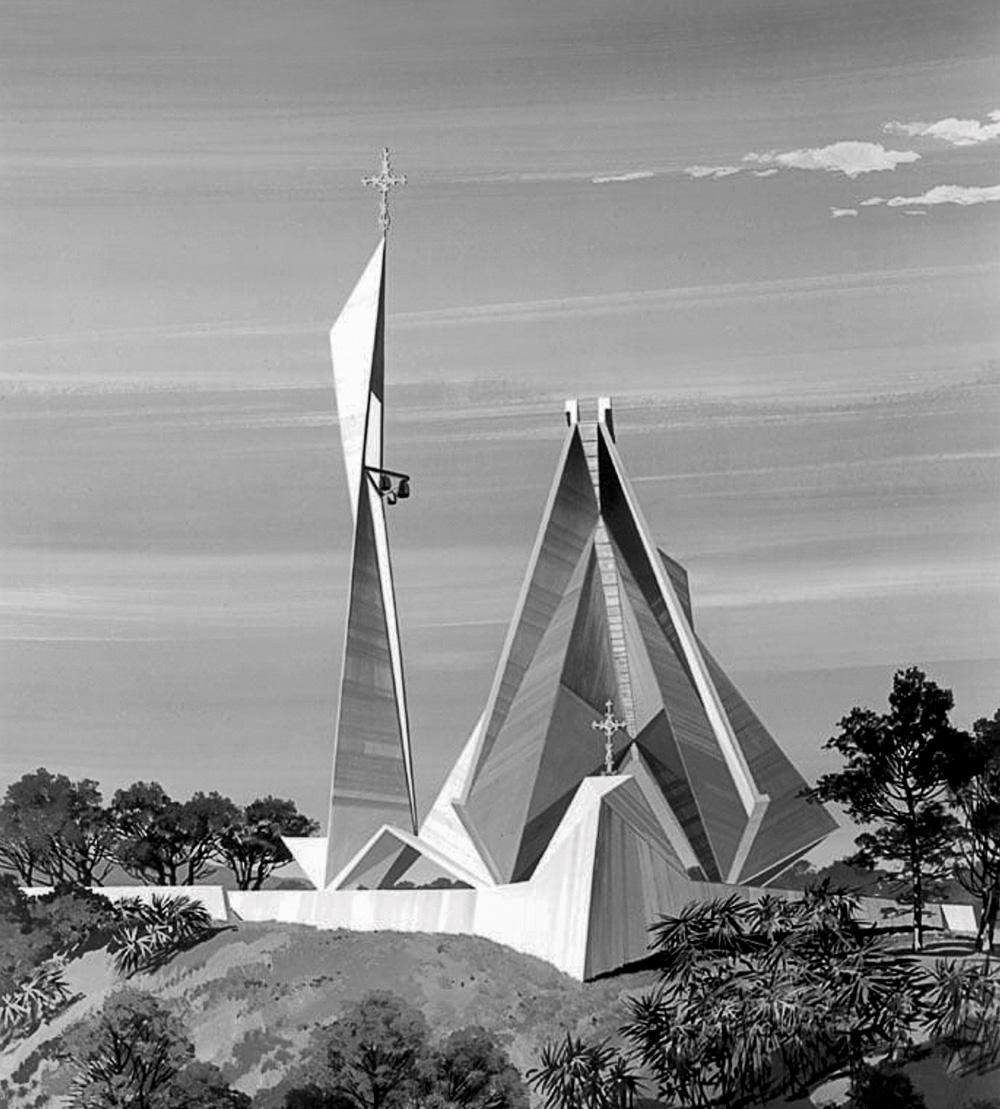

Inter-American University Chapel, IM Pei, San Germán, Puerto Rico, 1961

Shortly after starting his own practice, the young architect IM Pei entered a competition to design a chapel for the Inter-American University, a private Christian institution in Puerto Rico. Located on a hilltop site in San Germán, at the southwestern corner of the island, Pei’s proposed building was wrapped in a hood of folded concrete planes, like origami, a jewel or perhaps a strange insect. It opened to the elements on all sides and framed views of both the surrounding forests and the Caribbean Sea, while offering protection from strong sun and tropical rains. A narrow light slot in the roof admitted a slice of sky and beams of filtered daylight. The structure perched, as if about to take flight, atop a wide stone plaza jutting over a steep promontory.

Pei never shied away from borrowing from his unbuilt work, and the chapel’s X-shaped carillon would to some extent inspire his Joy of Angels Bell Tower at the sanctuary of Shinji Shumeikai near Kyoto, Japan—which he designed twenty-five years later. Pei did not win the competition, and the chapel, an octagonal building with a shooting spire designed by Ramírez and Ramírez de Arellano architects, opened in 1967.

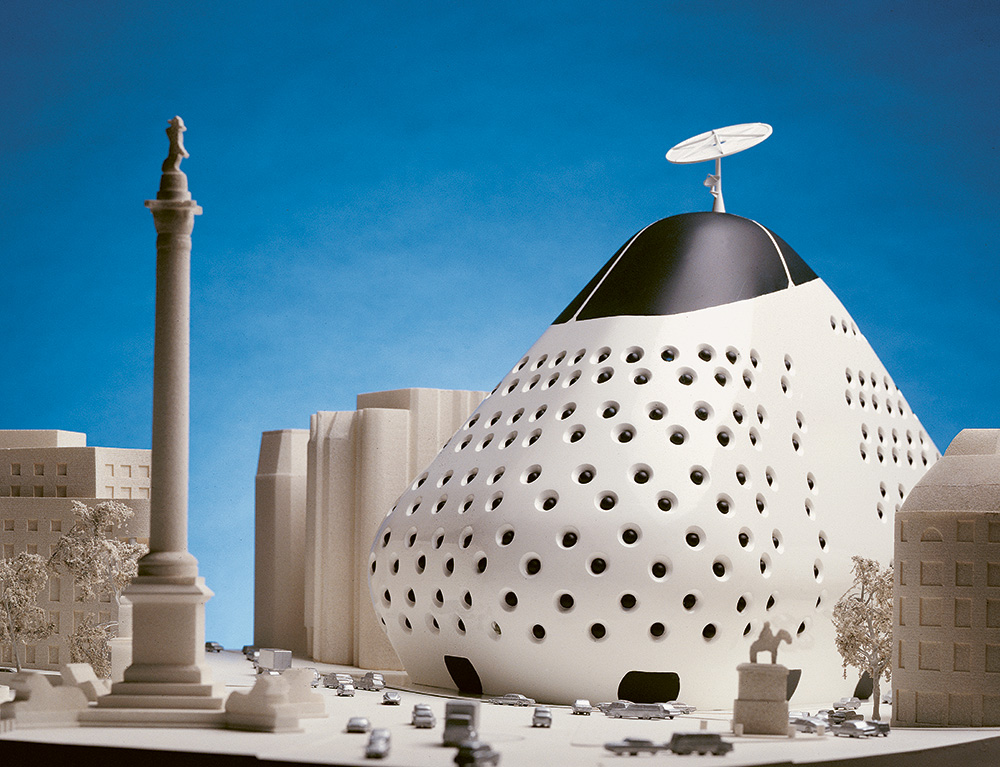

Grand Hotel Trafalgar Square Replacement, Future Systems, London, UK, 1985.

London’s Grand Hotel, a Victorian building of Bath stone on the southeast corner of Trafalgar Square (address: 1 Trafalgar Square), could have become a pyramid-shaped blob resembling a humidifier. Built in 1879, the original edifice – its colonnaded mass lunging towards Nelson’s Column – was by 1984 beset with structural problems, including decaying stone and severe subsidence. The hotel announced an architectural competition for its replacement. The most talked-about entry was by Future Systems, led by the futurist Czech architect Jan Kaplický and the avant-garde UK designer Amanda Levete. Their proposal, aptly called “The Blob,” was a tapering form clad in white ceramic tiles, supported by an internally stiffened skin dotted with deeply inset circular windows.

The odd shape was in fact quite practical, designed to maximize floor-plate area within the envelope permitted by the planners, and allowing maximum sun exposure for a hemmed-in site. Atop the humidifier/spaceship/Hershey’s Kiss was a deep, truss-supported roof deck. According to Kaplický, the design – easily the least contextual building in the competition – was too far ahead of its time. “It’s extraordinary how we started to create plasticity some time ago, and at that time people didn’t have a clue what it meant,” he told Icon magazine some years later.

The competition-winning design, by London practice SidellGibson, could not have been less similar. The firm demolished the hotel and replaced its facade with a virtual facsimile. But the frontage of what is now called the Grand Building is a stage set of sorts; inside, the glassy, modern interior atrium, airy and filled with shops though it is, could stand in for a corporate hotel anywhere.