Rafael Schacter’s latest book, Monumental Graffiti: Tracing Public Art and Resistance in the City is a study that challenges the way we (should) think and act in the places where we live. In an argument that overlaps with recent works such as Smooth City and the Designing Friction manifesto, Schacter similarly finds that the “frictionless” is an increasingly dominant logic of contemporary culture. It can be felt, for instance, in our experiences of the city as an “image curated and marketed as one commodity among a host of competing commodities”. Public spaces, Schacter argues to the contrary, should be spaces for activity, not passivity, they should be “a site for speech”. Graffiti is central to this argument because it is a kind of speaking for speech’s sake that actively challenges and rejects the normative uses of and interactions with public spaces; it “emerges through the medium of the city or not at all”.

From the outset it is made clear that this is a serious book about serious social challenges. As such, there is no reheating of ready-made tabloid arguments about graffiti being vandalism, ornament, the naïve art of disaffected youths, or else a gritty (yet bloodless) kind of state-sponsored street display. Rather, in carefully studying the culture of graffiti as a curator and anthropologist, Schacter raises important questions about urgent cultural issues. He achieves this through an unusual thesis that argues for graffiti to be reframed as a “monument”. Pulling at the stray etymological edges of the word “monument”, Schacter describes graffiti as a “reminder, advice, or warning”, it is a “publically positioned artifact […] imposing itself on our bodies and minds”. Thinking of graffiti in this re-evaluated way makes these banally familiar street markings strange and therefore noteworthy.

The book is made up of three parts: “Form”, “Message”, and “Trace” which respectively treat graffiti as art, act, and artifact, or: “as material image, as technique of citizenship, and as urban trace”. Schacter begins the book by describing graffiti as something that “binds”, “fuses” and “bonds” with the city rather than being a mark, stain, or layer on top of its official structure; it is not a dirty image on a clean substrate. Rather, graffiti is “written into the city itself”. It is not clear from the start but the types of graffiti Schacter is writing about are not the random bits of scribble in public toilets or the stuff gouged into school desks. There is something more achieved to the graffiti he is interested in, either in its craft and skill or else in its persistence and volume. For instance, Schacter has a connoisseur-like appreciation for the deeply embedded inseparability of acid etched tags in glass, the way a “two-color throw-up” might discard architectural limits, the relatable-scale of graffiti’s “anthropometric proportions”, the discerning anatomy of the text-image form, and the seeming permanence of scratchiti. These particular kinds of graffiti are global and complex, and they are incorporated in a broad array of subcultural interests “from punk and football hooliganism to situationism and heavy metal”. This multiplicitous complexity of graffiti is subtly presented through the pithy opening lines of each new chapter, in which graffiti is variably described as “a public artifact”, “an object existing only via its style”, “a time-based form”, “a participatory act”, and so on.

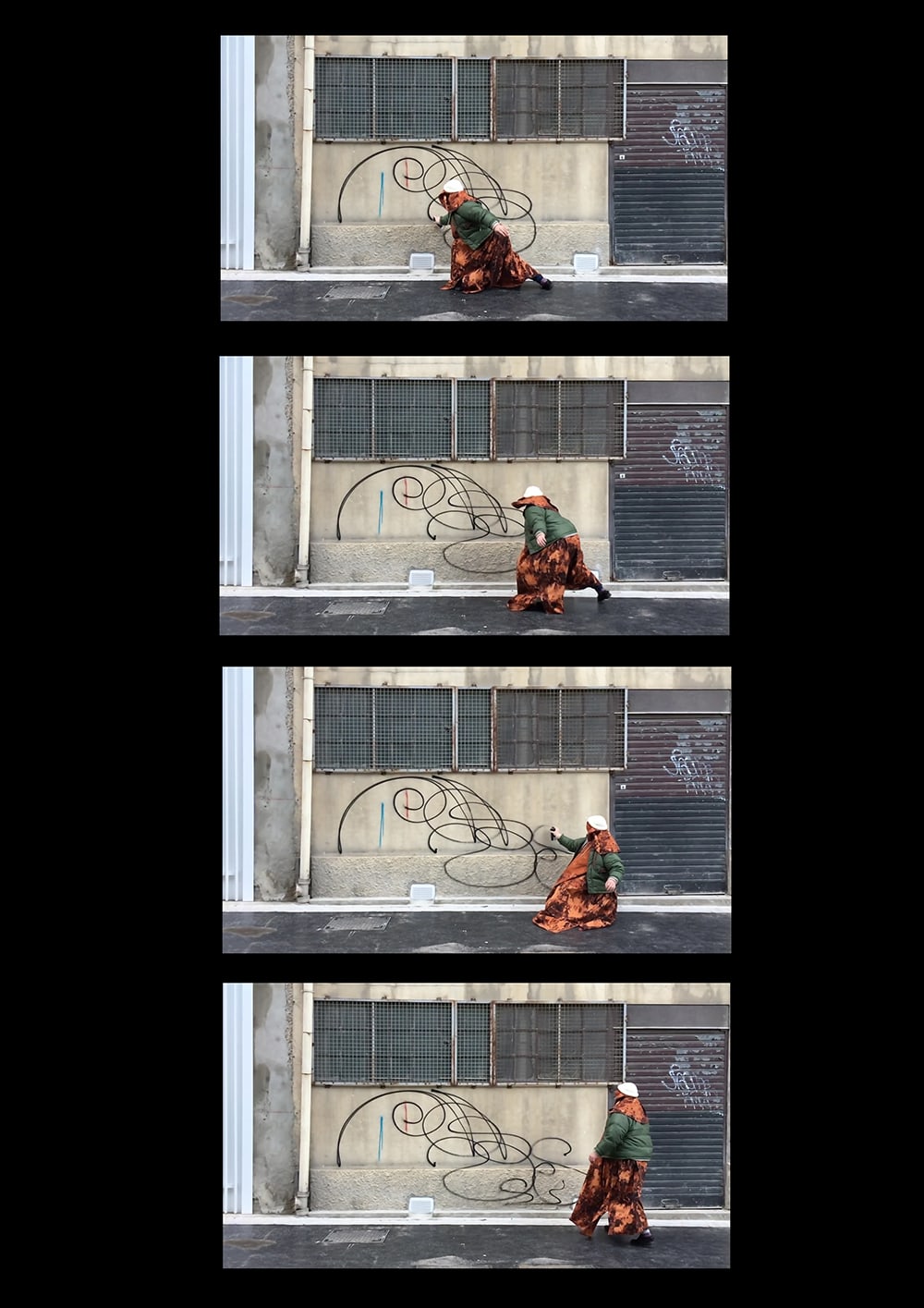

HONET, Paris 2020. Courtesy of the artist. Image supplied by MIT Press.

The book can be read, Schacter tells us, “forward or sideways”. For instance, one reader might follow the given order, page by page, but another reader might leapfrog across common themes in different chapters: space and appearance (chapters 1, 4, and 7), body and visibility (chapters 2, 5, and 8), temporality and sociality (chapters 3, 6, and 9). Encouraging these perambulatory steps is well-intentioned but seems unsupported in the book’s design which could have offered more compelling visual clues, or tactile markers and incentives to provoke a reader to wander in this peripatetic way without concern for the usual, well-trodden path: cover-to-cover. That being said, the sober, plain-faced design of the book works well without attempting to pilfer the visual language of “the street” — stencil typefaces, ink drips and splatters, for instance — the only suggestion of the materiality of graffiti is unintentional, it is under the sleeve, on the spine of the book, in the slight imperfections of the debossed print. The ink’s bleed, hairline cracks and flaking are easily scaled up in the reader’s imagination to the size of a train carriage or a disused factory wall.

The book is illustrated with hundreds of color photographs; the images don’t register like samples taken from the field, or as a carousel of slides presented in a tweedy lecture. Instead, they feel much warmer, like Schacter has pulled them, dogeared, from his back pocket and is proudly rifling through them like a fanatic sharing a well-loved obsession. In this way, Monumental Grafiti at times reads as somewhere between the idiosyncratic micro-focuses of The City is Ours and the peculiar intellectual expressions of Nick Papadimitriou’s deep topographic study Scarp. Despite this zeal, there is still a taut line of academic diligence that runs through the book which at times, cuts a touch too deeply into the text and chokes the more raw sincerity of Schacter’s otherwise impassioned voice.

Beyond the passages of involved academic rhetoric, there are pops of contrast in others that read as if they are being read out loudly by Schacter, as if he were standing on a big block of rebar-sprouting concrete addressing a modest audience in a forgotten nighttime edgeland; they’re animated, lively, and they need you there, reading carefully. And there are other moments that read like lucid conversations a shoulders-width apart, spoken over the noise of traffic as you wander with Schacter through daylight-streets seeing the city like you have never seen it before; it’s introspective, personal, eye-opening and it reads like it would be going on whether you were there or not, you’re a passenger on his journey. It’s not clear if these different registers are intentional or if they have come to be clipped and pasted together over the many years of research, writing and editing that make up this appropriately palimpsest-like thesis on graffiti. Regardless, they are compelling and seemingly written without being self-conscious of their effects.

MOSA,Untitled, 2022. Courtesy of artist and Tramontana Magazine. Photo: Elliot Sitbo. Image supplied by MIT Press.

There is an undeniable agility in Schacter’s writing, it’s there in his unusual approaches to the materiality of graffiti, and in the unexpected associations he makes between graffiti and art history, and in the left field positions taken in his arguments. This dexterous novelty never reads like academic slights of hand — as a way to cynically carve out his own unique contribution to research on graffiti — they read as the consequences of original and vigilant research that has come out of a thoroughly immersed, deep ethnographic engagement with graffiti culture. In the introduction, Schacter even modestly explains that “the basic arguments posited here have in fact all come from my interlocutors themselves”, that is to say: the graffiti writers.

With this in mind, it’s not often clear who the intended readership of Monumental Graffiti actually is. Whether it is the general public, researchers in adjacent fields, or the graffiti writers themselves. Ultimately, it doesn’t really matter, and ideologically it is fitting for the book to resist the market logic of targeted audiences. Arguably it seems Monumental Graffiti is about (and for the sake of) what makes up “the fabric of the metropolis”. Consequently, just like a city, there are parts of the book that will feel more welcoming than others but it is worth considering, without those less welcoming places, who and what might be excluded.

Monumental Graffiti targets the pacifying of public interactions brought about by the malformation of the city as an ascetic site for privatisation; something in direct conflict with the city as a communal place of habitation. As such, more than a gesture, or an individual’s voice or personal expression, or else vandalism and senseless crime, for Schacter, graffiti is a monument to participation, and to a presence that might not fit well with the smooth aesthetic of the well-designed cityscape. As such, graffiti is a monument “to our right to the city itself”. Because graffiti is, by its material nature, an “impermanent monument” it has no nostalgic trappings, as Schacter says, it is “speaking in the present tense”. Therefore, thinking about the present as a moment when many are needing to urgently reimagine the aesthetics of resistance, dissensus, alterity, and otherness, Monumental Graffiti is required reading.