The following is an excerpt from “Making Home Belonging, Memory, and Utopia in the 21st Century” edited by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Christina L. De León and Michelle Joan Wilkinson. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press, 2025.”

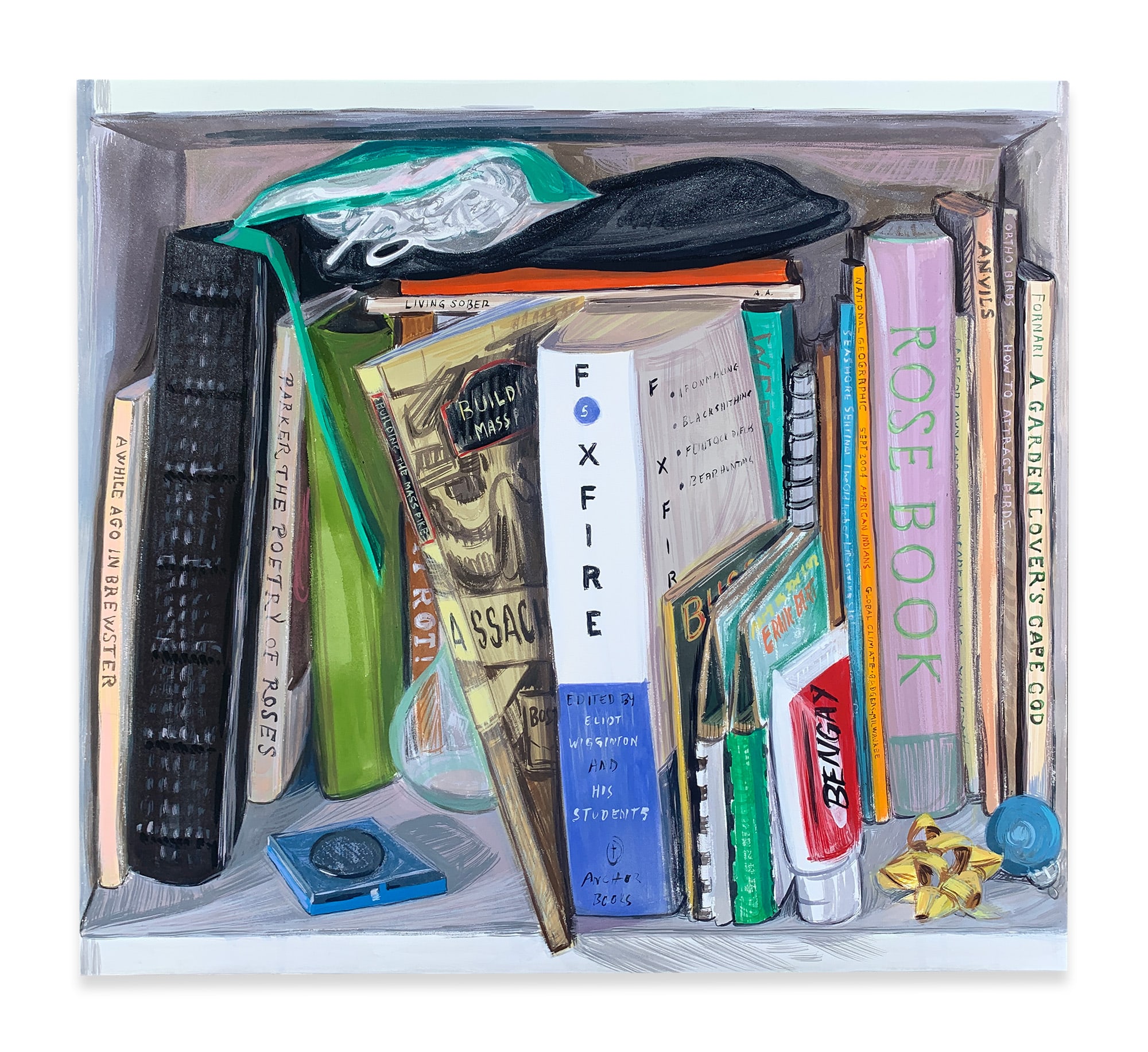

After her father’s death, Josephine Halvorson made paintings of his home office. Nothing exceptional, just his regular stuff arranged as he had left it. In one, Dad’s Bookshelf (2020), books on gardening and Massachusetts history are wedged beside a tube of Bengay, a stick-on gift bow, and a stray Christmas ornament. At the heart of the painting is a thick spine that reads Foxfire. The cover is only partially visible, listing the book’s contents: ironmaking, blacksmithing, flintlock rifles, and bear hunting. Halvorson’s father, John, was a blacksmith who installed woodstoves around Cape Cod for half a century. In this haphazard portrait, the book acts as a stand-in for his working life.

My dad also had Foxfire books—actually, they were the only books I knew him to care about. Our family gifted him one every holiday, birthday, and Christmas throughout my childhood, each one dated and inscribed “With love” in loopy kid-cursive. When he died, in 2021, the stack of Foxfire books was his only possession I wanted for myself. Now the dozen-some books reside in my Brooklyn apartment, where I glimpse them peripherally throughout my day.

Halvorson’s painting is both a memorial of her father and a meditation on transience itself: a picture of life arrested, made suddenly meaningful by her loving transcription of it. That real-life bookshelf must be packed away by now, or at least reorganized, destined, like everything, to change. While her painting may be a reminder that all things must pass, it also suggests that, if properly cared for, the things we live with can endure. The spaces we inhabit are always provisional and contain a random assortments of things—junk and treasure, by turn—given meaning by the lives they bind together and the qualities of life they enjoin.

Foxfire started in 1966 as a quarterly magazine made by a high school English class at the Rabun Gap-Nacoochee School in rural north Georgia. The students named it after a local phosphorescent fungus that grows on decomposing wood. The inaugural issue has three sections. The first is devoted to oral histories from the people who lived nearby, including a transcript of a retired sheriff describing the Clayton Bank robbery of 1936, an interview with an “anonymous Rabun Gap Man” about moonshining stills, and assorted home remedies. The second section includes works by professional writers, such as the poet A. R. Ammons, with the third section reserved for creative writing by the students. It is illustrated by woodcut prints and amateur photographs, all laid out and produced as inexpensively as possible by the students themselves.

A decisive turn came for the trajectory of Foxfire when the class agreed they were most interested in the first section, charting their own lives by engaging the place they inhabit. Locals also responded to those pieces, creating a clear audience to address. Soon Foxfire came into focus: students would go out and talk to folks tucked in the mountains, asking to be taught various skills. These people, rural Southern whites, are regularly degraded in the popular imagination as backward hillbillies. But the students recognized a vanishing world around them, where people made almost everything they had, primarily bartering goods and services outside of the monetary system. It might not be “better” than the world they were entering in prosperous, increasingly connected, postwar America, but it certainly had its own integrity that deserved recognition.

Foxfire took off nationally, unexpectedly intersecting with the counterculture’s interest in experimental education and back-to-the-land movements. A write-up in the Whole Earth Catalog, the bible of alternative living, concludes: “The thing I like most about it is the way these kids are looking immediately around them for their inspiration, instead of taking cues from New York and California. In their own way, these people are as hip and sophisticated as any young people putting out a magazine on either coast. More so, even. They’re cooler, more adult. These kids in Georgia are living in a real world, studying real things, and in consequence they are creating a wonderfully real publication in Foxfire.”1

The Foxfire archives—comprising approximately 3,000 hours of audio, 90,000 photographic slides, and 2,000 oral histories— reveal the unique process of putting together this publication and the seriousness with which these high schoolers regarded it. An “assignment sheet” from fall 1969 begins with the direction: “Make sure the material you turn in is absolutely accurate and complete. At the very least, we owe our readers that. They paid for it. And we have a reputation to protect.”2 Editor Paul Gillespie charges his classmate Jean Kelly with interviewing Mrs. Ada Kelly:

Your Assignment: As you may know, the next issue of the magazine is devoted to all the ways a person could finish and furnish a log cabin after the walls were up and the roof on. In other words, what did he do next? What part would the woman play, and what would the man contribute?

Having talked to your grandmother several times in the past, we thought you might ask her for some leads for the next issue since she’s been so helpful before. She might be able to give us ideas, and even show us several things that might have gone into an old log house that the family would have made themselves. We need directions for making many of these things, and photographs of them if possible.3

At the bottom of the page, Jean Kelly typed a response:

My grandmother has these things which might be helpful:

Smoothing irons churn and dasher Kraut cutters Scales

beeswax for sealing

Trove for splitting boards for roof

Photograph of the log cabin where she was born

A large pot used for washing clothes

Butter mold and paddle

Coverlet made by her mother (a rose and vine design)

She says it’s o.k. to make pictures.

She also said the cracks between the logs in the cabin were filled in with red clay mixed with water and left a little rough on the outside usually smooth as possible on the inside with a small paddle. Some of the cabins were left with the red clay showing but many were white-washed every day, with a white clay mixture making the cracks smooth and white.4

This simple document captures so much of what is extraordinary about Foxfire. Unlike trained anthropologists, outsiders who invariably bring their own cultural biases to their studies, these students were reaching out to their own extended families, forging a unique framework of trust and accountability. There was equal attention given to the labor of women and men, and the predominant whiteness of the region is complicated by the regular inclusion of Black Appalachian neighbors like Beula Perry, who demonstrated basket weaving, and an early issue on Cherokee life in the region. The evident respect with which the students approached their “contacts” was not left to an unspoken agreement; a contract was formalized with the people they photographed and interviewed, stating, “I understand that at no time will this material be used in a way slanderous or detrimental to my character.”5 Such a statement is a measure of the contacts’ sensitivity and the trust they shared with the students, a consecration of their entire way of life.

By the end of the 1960s, the magazine’s small print runs were swiftly selling out with increasing demand for back issues. The students were approached by an editor at Anchor Books, a division of Doubleday, about compiling an anthology. The Foxfire Book was published in spring 1972 to wildly enthusiastic reviews in the national press, with Life sending a reporter and photographer to Georgia to write a feature. The result was a genuine phenomenon, with the book shooting to the top of the New York Times best-seller list and staying there for thirty-five weeks. All the royalties went directly to the Foxfire organization, which the students administered and where they reinvested in their project, buying new equipment and paying for administrative help.

The cream-colored cover of The Foxfire Book promises hog dressing, log-cabin building, mountain crafts and foods, planting by the signs, snake lore, hunting tales, faith healing, moonshining, and other affairs of plain living. There has been so much fascination regarding the subject matter that relatively little attention has been paid to the sophistication of the book’s form. Take an early piece, which introduces one of the great stars of the Foxfire series, Aunt Arie, a woman in her eighties who lives by herself in a small mountain cabin without electricity or running water. Readers first encounter her trying to pull the eye out of a severed pig’s head. The setup: “Aunt Arie’s conversation was so interesting that, rather than summarize what she told us, we have let her speak for herself.”6 When asked if she minds doing such bloody work, she replies: “I don’t care fer’t bit more’n spit’n’th’fire. Ah, I’ve just done anything’n’ever’thing in my life ’til I don’t care fer nothin’ ’at way. I don’t. Nothin’ just don’t never bother me, what I mean, make me sick. They lot’s people can’t when t’blood comes’bad’n’s’bad’n’s’bad—they run off’n leave it. They can’t stand it. I don’t pay it a bit’a’tention in th’world.”7

There is no set template for this kind of transcription; the students just had to sound it out and do their best to make it read exactly as it was said, grappling with the phonetic transcriptions of speech as precisely as possible while retaining a matter-of-fact tone. Taking seriously the textures of language as it is spoken brings the Foxfire books closer to the realms of literary modernism than to the folksy, backward mountain-folk clichés that dominate popular culture.

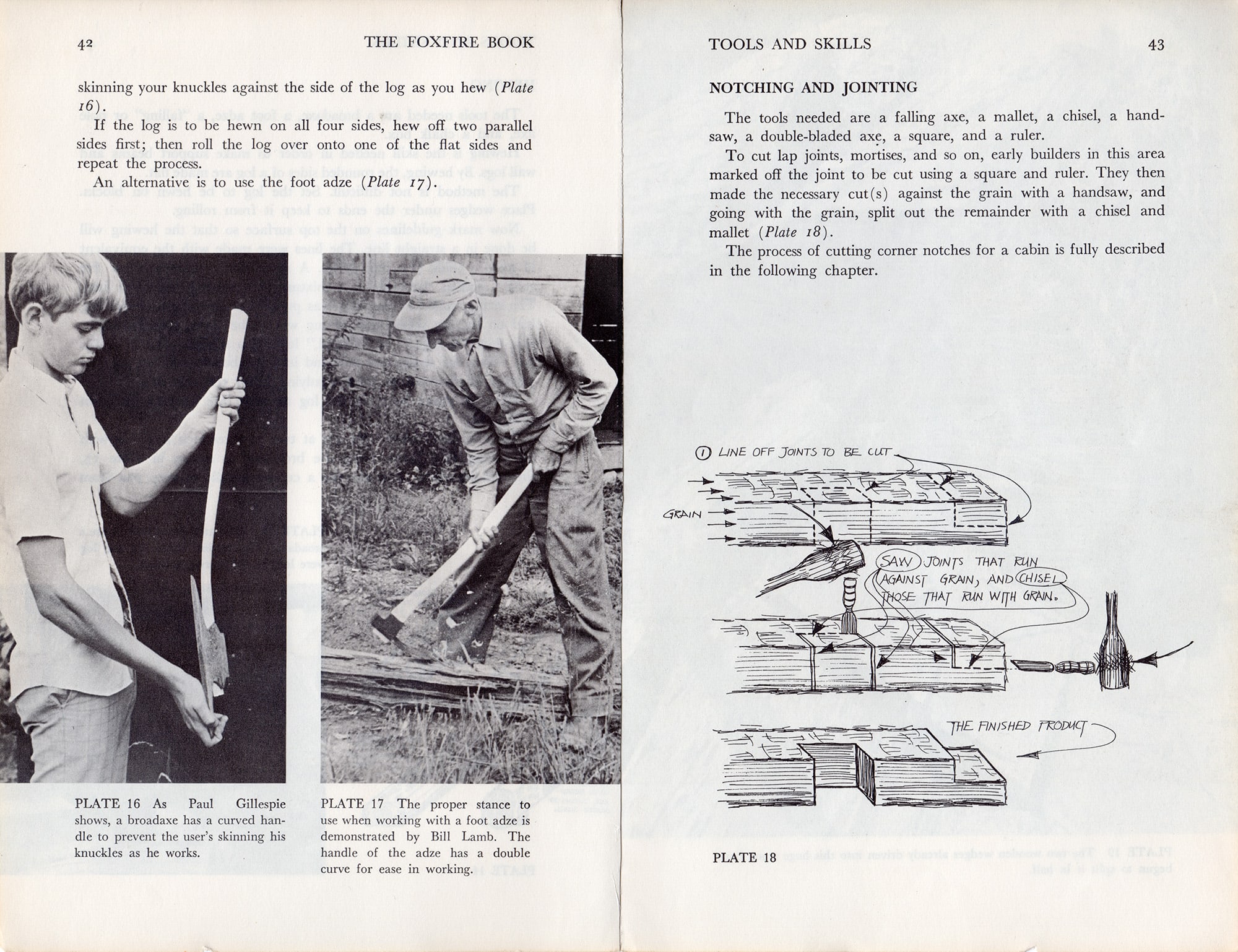

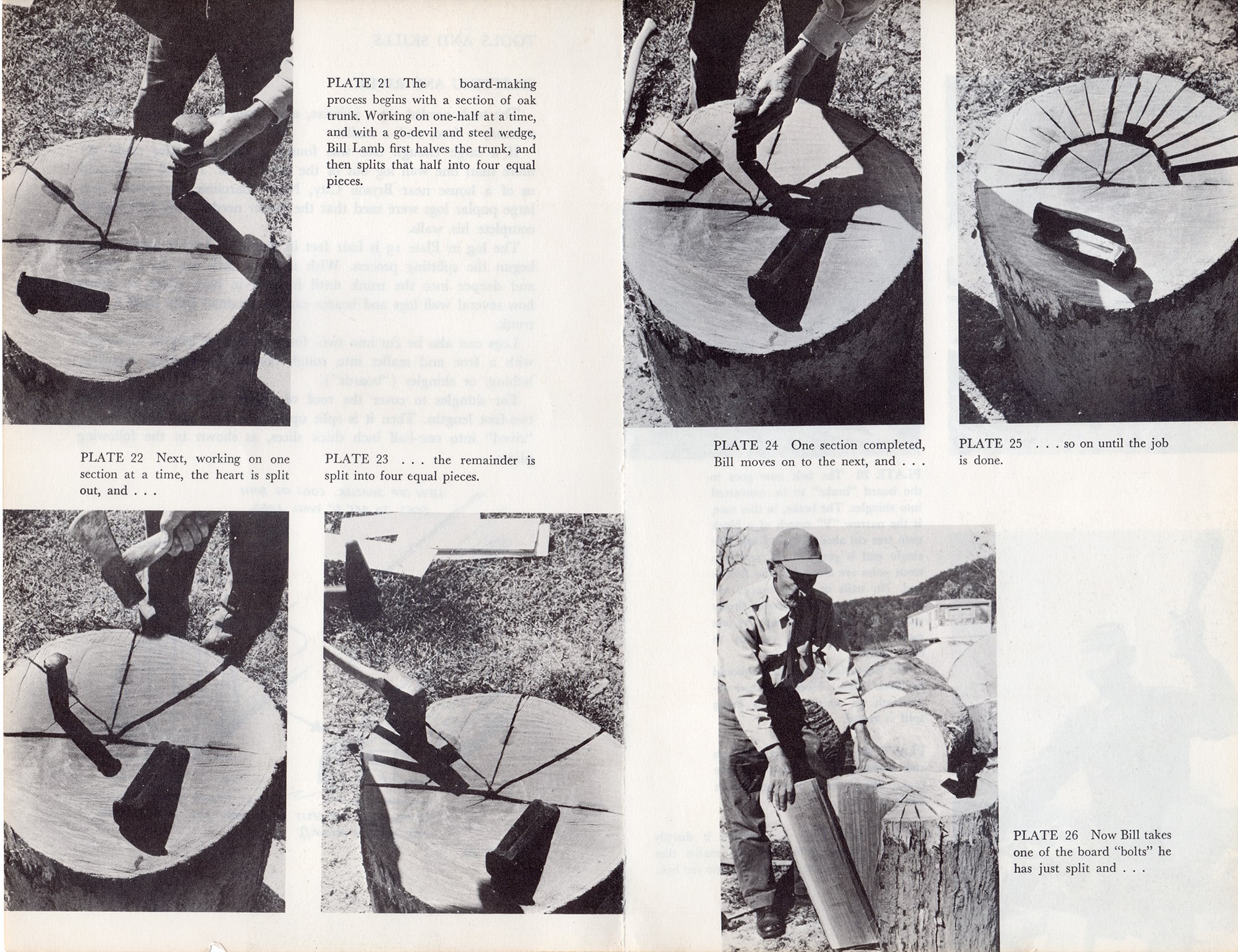

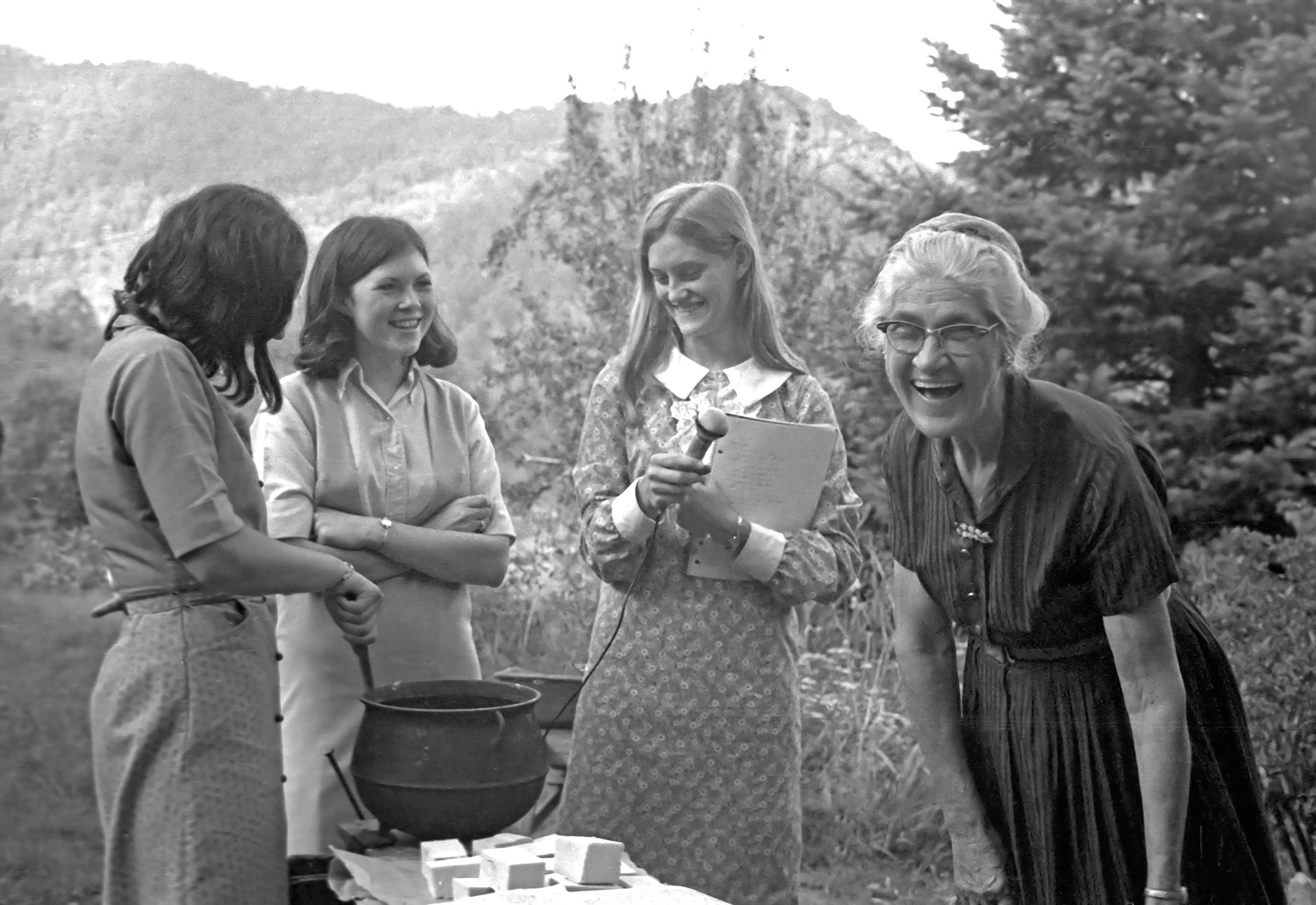

This approach was matched by the heavily visual layouts; all the photographs were shot and developed by the students themselves and the diagrams were hand-drawn. The images pinpoint the practical information in the text, illustrating two woodgrains meeting in a dovetail joint or the correct hand position for weaving oak splits into a basket. Often people and things are shown from several vantages, creating multidimensional collages. There are also very loving portraits of older people, sometimes smiling and talking, but mostly shown in the midst of work. The result is an image-text tour de force of observational, process-driven writing: this is what happened, this is who does it, this is what each step looks like— this is what you need to know to do it yourself.

One extraordinary sequence, which occupies about a quarter of The Foxfire Book, is an in-depth discussion of the kinds of trees located in the region, outlining what each type of wood was traditionally used for and why. It is followed by a richly illustrated section on tools and skills, showing Bill Lamb as he splits a log into boards. One spread of five images describes how a log is cut in half and then into four equal wedges, which are then each split into four more. The effect recalls the procedural performances and conceptual art of the 1960s and ’70s, many of which document mundane tasks. This is all groundwork for the feature article, “Building a Log Cabin,” synthesizing information the students had gathered from interviews as well as analyses of every log cabin they could find in the region, and again concluding with a point-by-point image-text demonstration. Like everything in the Foxfire books, the instructions are clear enough that you could use them to build your own cabin (which people did) without being technically minute or pedantic. Each feature is punctuated with anecdotes and variation, with explanations on how and why alterations occur; the feeling is that these are structures made to be adapted to a particular need and circumstance—try it and find out.

Spread from The Foxfire Book, Book One, 1972; Courtesy of the Foxfire Fund © Penguin Random House

With the success of the first book, the publisher immediately requested a second. Foxfire 2 came out the following year, bringing together more oral histories, addressing everything from raising sheep to weaving cloth, midwifery, and burial customs. For decades, an ever-changing group of local high school students continued this work, with the first five volumes coming out in the 1970s, followed by four in the ’80s, two in the ’90s, and the final numbered volume, Foxfire 12, published in 2004. Many individuals reappear throughout the books, creating a beautifully variegated world that both deepens and expands across the series. Thematic collections have also been published, drawing from Foxfire’s vast archives, including a cookbook and an anthology devoted to Appalachian women.

Continuously in print for fifty years, Foxfire has permeated the very fabric of American culture across the ideological spectrum, as likely to appear on the bookshelves of a fundamentalist church as a radical commune, entering the homes of a New England blacksmith and a Florida farmer, where, respectively, Halvorson and I encountered it. By that time, the older people photographed and interviewed in the 1960s and ’70s were long dead, and the first generation of high school students found themselves to be elders.

Today, just as easily as in 1972, you can pick up The Foxfire Book and learn how to make soap out of bacon grease and lye, as Pearl Martin explained it to her granddaughter and a few of her friends from school. You can see how Martin wore a nice Sunday dress because she knew she would be photographed, despite the work being messy. Because the girls who interviewed Martin had a tape recorder in addition to cameras, the instructions are interspersed with loving interactions that speak to her relationship with her granddaughter. Alongside information about soap making, you also get to eavesdrop on a scene in which the girls crack the old lady up by asking if they can put perfume in the soap. She responds: “Youn’s want me t’put perfume in there? I can perfume it up for your’s if you want. But I’ll tell you; if for me, I like t’smell that. It smells like old times. I’ve washed with homemade soap s’much—it smells like homemade soap.”8

And with this tender portrait, readers are empowered to try it out for ourselves with our family and friends. We can produce that soap, use it in our homes, give it away, and tell our stories about it, all in celebration of the humanity of things, of our collective capacity to remember the dead through living, making, and handing down. Taken together, these stories are a unique achievement in the techniques and practices of making a home; Foxfire is a monument to life on Earth.

Excerpted from “Making Home Belonging, Memory, and Utopia in the 21st Century” edited by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Christina L. De León and Michelle Joan Wilkinson. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press, 2025.”

Listen to our 2021 conversation with Jarrett Earnest here. You can also listen to our 2021 interview with Alexandra Cunningham Cameron here and read our 2024 conversation with her about Making Home here.

Hero Image: Josephine Halvorson, Dad’s Bookshelf, 2020; Artwork © Josephine Halvorson, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

-

The Updated Last Whole Earth Catalog (New York: Random House, 1974), 152. ↩

-

Foxfire assignment sheet, student Jean Kelly 1969, Foxfire Archive, Mountain City, Georgia. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Foxfire permission form, Foxfire Archives, Mountain City, Georgia. ↩

-

Eliot Wiggington et al., The Foxfire Book (New York: Anchor Books, 1972), 20. ↩

-

Ibid., 21. ↩

-

Ibid., 154. ↩