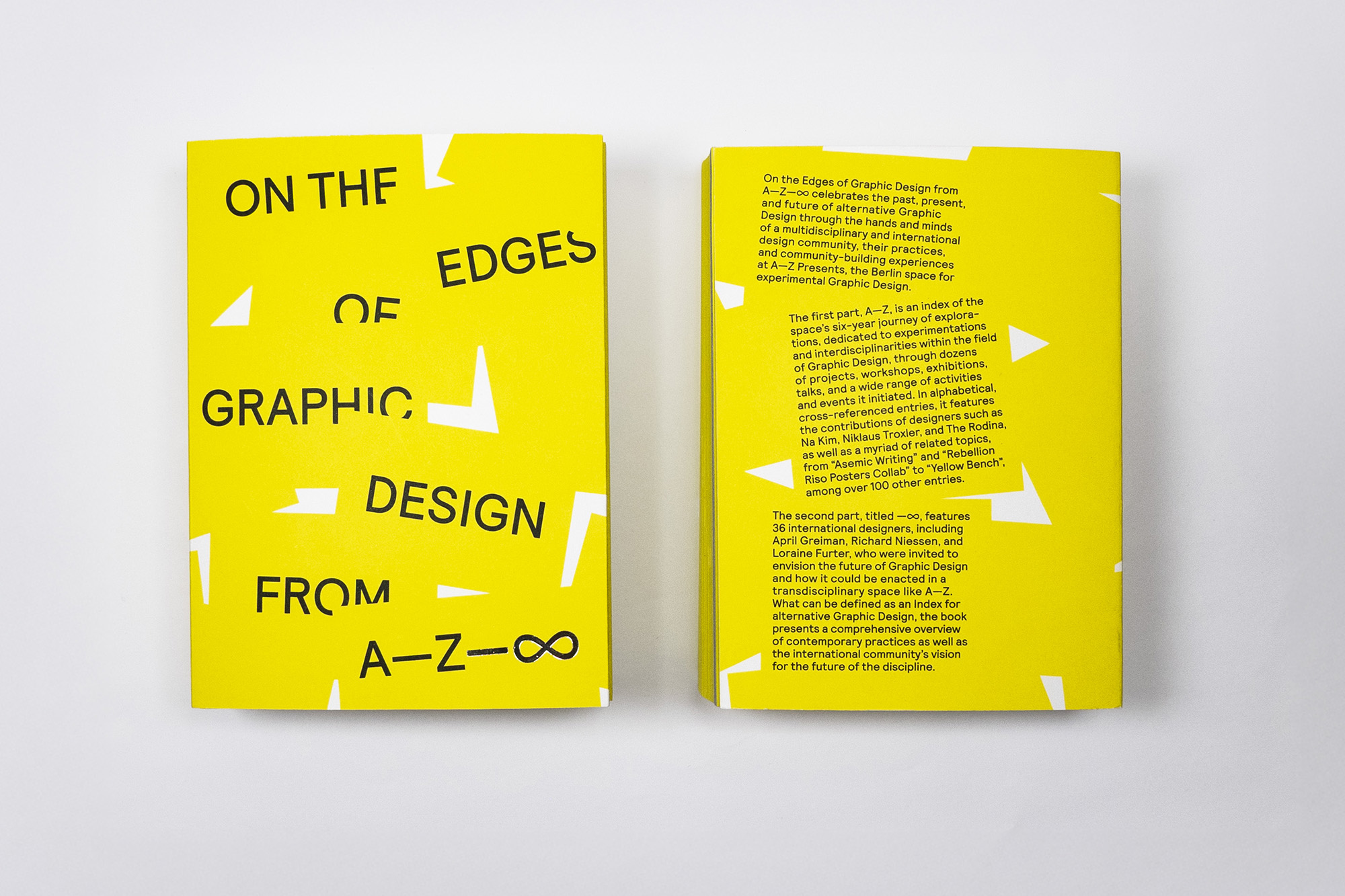

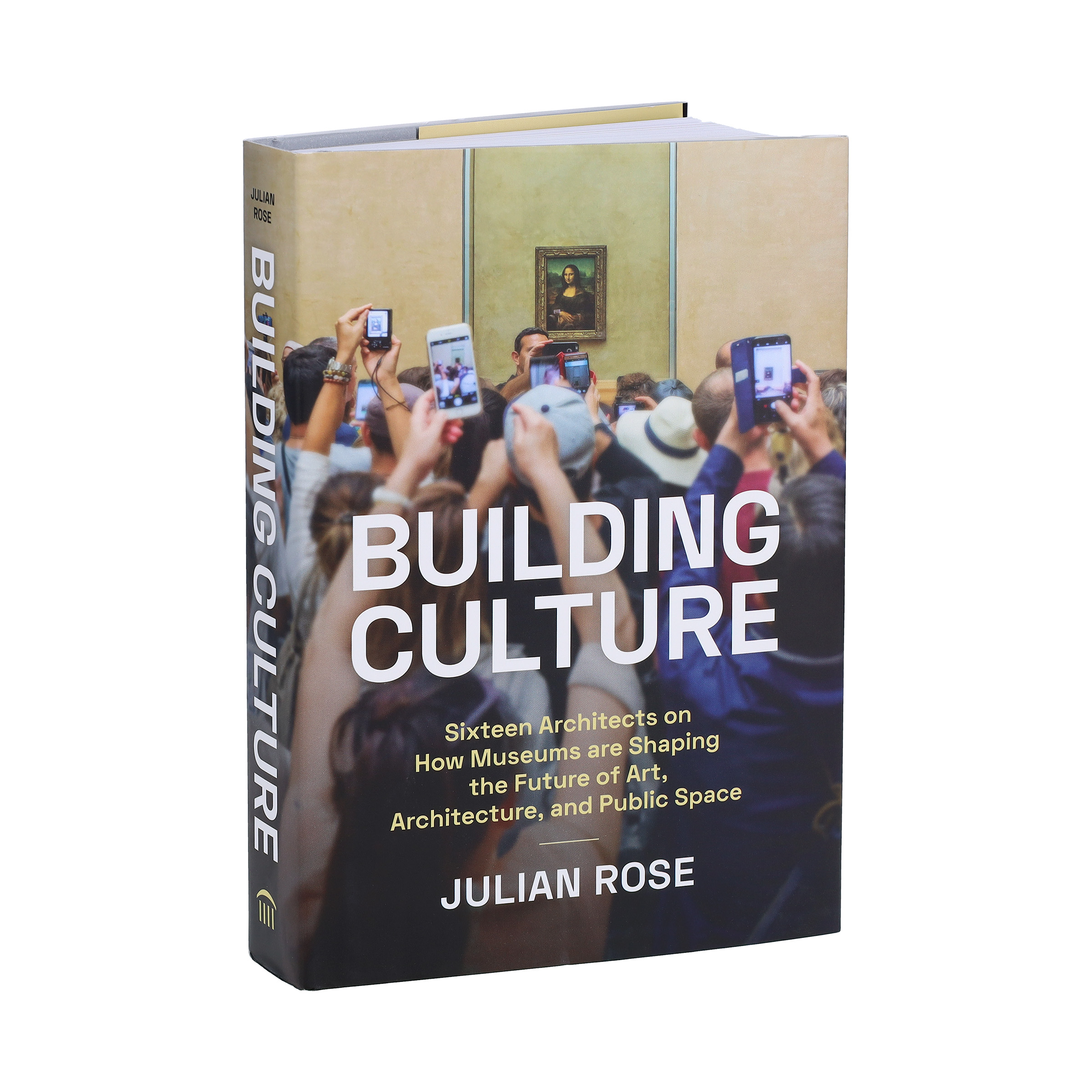

Historian and critic Julian Rose’s book Building Culture: Sixteen Architects on How Museums Are Shaping the Future of Art, Architecture, and Public Space, out from Princeton Architectural Press this month, collects a series of interviews about the complex process of creating spaces for art. Spanning generations, geographies, and methods of practice, the conversations illuminate the diverse influences and concerns that combine to create institutions that are increasingly central to public life both in the United States and around the globe.

In celebration of this new publication, Scratching the Surface shares Rose’s interview with Kazuyo Sejima. Since cofounding the architecture studio SANAA with Ryue Nishizawa in 1995, Sejima has been celebrated both for the extraordinary material and tectonic refinement of her structures and for her careful attention to the social life of buildings. She and Nishizawa were awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2010, and in recent decades they have brought their unique talents to bear on a number of innovative exhibition spaces around the globe, from the New Museum in New York to the 21st Century Museum of Art in Kanazawa to intimate galleries constructed on remote islands in Japan’s Seto Inland Sea. Here, Rose speaks with Sejima about the profound experiential effects that can be achieved within museum space.

JULIAN ROSE – A conversation about museums is also, inevitably, a conversation about the relationship between art and architecture more generally, so I’d like to begin by asking you about your first encounters with visual art. Was art part of your curriculum as an architecture student? Were there artists whom you admired as a young architect or who influenced the development of your practice?

KAZUYO SEJIMA – Not at all. In Japan, architecture and engineering are closely linked and are normally taught in the same schools, but art is separate. Only a few art schools have architecture departments, and they’re very small. That is gradually changing, but here architecture is still more associated with industry than with art.

JR – I’m surprised to hear that, because the materiality of your work reflects what could be called, for lack of a better term, an artistic sensibility. Your use of glass, especially, involves extremely subtle and sophisticated plays on the relationship between physical movement and visual perception. And, presumably for that reason, critics have linked your buildings to the work of artists such as Donald Judd and Dan Graham. But of course their work, in turn, could be said to address fundamentally architectural problems, so there is no reason you would have necessarily arrived at your current practice through visual art. It sounds as though your first training with materials like glass, aluminum, and steel was practical, even scientific.

KS – Yes, purely technical. I didn’t have much experience with art until I started designing museums.

JR – At what point in your career did you begin doing that?

KS – The 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa was the first big museum that Ryue Nishizawa, my partner in SANAA, and I did. It opened in 2004, and the competition was a few years earlier. But before that there were some smaller projects for exhibition spaces, like the N-Museum in Wakayama [1997]. There, the client asked for just one very small gallery to show the work of painters from the area. Traditional Japanese paintings are very sensitive to sunlight, so the main function of the gallery was to protect the works.

JR – Many museums want to bring as much natural light as possible into their galleries, but in this case you had to keep it out.

KS – The main gallery became a concrete box. It was very generic. But if the same concrete volume had become the facade it would have been unfriendly, so we surrounded the box with a glass corridor that is large enough that it becomes a public space in itself, to be used by the local people.

JR – Inventive interchanges between circulation space and gallery space are a hallmark of your museum designs. Often architects try to either hybridize them—as in the familiar enfilade of most neoclassical museum buildings—or separate them completely, which usually results in vast galleries with stairs and corridors pushed to the perimeter, as in the Pompidou Centre or other open-plan museums. In Wakayama, it sounds like your approach to this relationship evolved from the exhibition requirements of that specific collection. Kanazawa is a museum explicitly dedicated to contemporary art, which is more amorphous. What did you know about the collection, and how did that knowledge inform your approach to the design?

KS – Yuko Hasegawa, the museum’s chief curator and founding director, was deeply involved from the beginning. We learned a lot about contemporary art while working with her. But we also learned that our principal role was to understand the relation between the building and the art and to think about that relation in terms of the visitor’s experience. For example, when you walk through a museum, sometimes you want to go back to see one piece again. It’s a little bit boring to simply retrace your steps, so we considered connecting the gallery spaces in many different ways. It was an interesting challenge. Of course, if the design gets too complicated, that is also problematic.

JR – So you saw your role less as responding directly to the art than as framing its relationship to the viewer and, in the process, finding a balance between simplicity and complexity.

KS – Yes. In that way, a museum building should be like a city. It’s boring to immediately understand everything. But it should not be impossible to understand, either. Every time you go back, you should get to know it a little better.

JR – That’s a particularly good analogy in the case of Kanazawa, because there is not just a variety of pathways through the building but also a mix of private and public spaces, including amenities for the community. Were some of your conversations with the curator also about how to make it feel more accessible?

KS – The 21st Century Museum is a public institution. As is typical for a building like this in Japan, the program was defined by the local government. At the time of the competition, more than twenty years ago, contemporary art was still not very popular in Japan. There were many citizens who might protest spending money on that. So the government decided to make two buildings on the site, one a museum and one a kind of community center. We proposed to combine the two, and we won the competition.

JR – That’s beautiful, but it also sounds almost paradoxical. How did you mix those elements within one building?

KS – It’s not like a gallery is always quiet and a public space is always busy. It’s strange to create such a sharp distinction. And also, for us, the museum’s focus on contemporary art meant that it should somehow be connected to contemporary society. So we tried to mix the gallery and the circulation, increasing the proportion of circulation space until the two were almost equal. At that point, it was not really circulation space anymore, but an area that could be used in different ways. Architecturally, our solution was to make a circular glass building, with public programs—a lecture hall, a library, a workshop—all around the facade. The perimeter is transparent, so it feels open, and there are four entrances to invite people into the building from all different directions. You don’t have to pay the admission fee until you get into the center of the circle, which is the museum zone.

JR – And the galleries themselves are pavilions, essentially small freestanding buildings within the outer glass circle. Were these structures simply a response to the necessity to create wall space? There is a long history of attempts to exhibit artworks in transparent buildings, and they’ve usually been unsuccessful. In Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the iconic transparent volume is really just an entry pavilion, with more traditional gallery space on the ground level below. Lina Bo Bardi famously invented glass easels to show paintings in her Museu de Arte de São Paulo, but they have rarely been used. In Kanazawa, were these gallery pavilions your way of reconciling the desire for transparency with the needs of the museum?

KS – It was also a way of introducing diversity into the exhibition space. The galleries have different shapes and different proportions—even different heights, ranging from thirteen feet to thirty-nine feet. And because all the galleries are independent, it makes the entire building more flexible. The curators can redefine the “museum zone” for every exhibition, changing which space is free and which space you pay admission to enter. They can also change how you enter the exhibition and how you move through it.

JR – That’s fascinating, because it seems like you’ve invented a new approach to flexibility. Architects and curators are always talking about how important it is to have flexible spaces in a museum, but that is usually defined at the scale of the individual gallery—say, with movable partitions. You’re providing flexibility across the building as a whole.

KS – We defined the plan, but artists and curators can develop it further. There is an opportunity for the architecture to be created through use.

JR – I want to return to the question of transparency. You mentioned the need to balance simplicity and complexity in planning your buildings’ circulation, and I wonder if there is a similar balance that you have to achieve in phenomenological terms. You don’t just use glass to create transparency—often you layer it or curve it to produce reflections and other visual effects that make the experience of moving through your buildings very complex. Is there a point where this begins to compete with the art?

KS – In the case of Kanazawa, there were some limits. We couldn’t achieve what we originally proposed, which was to have windows in the gallery pavilions themselves, to make visual connections among them. The curator asked us to make them opaque: no windows, only skylights. Some of the other programs—the conference room, the lecture hall—are in glass enclosures. In the Glass Pavilion we did for the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio [2006], we had more freedom, because the space is mainly for exhibiting glass works. So that meant we could think of the museum itself as part of the exhibition.

JR – That building is similar to Kanazawa, in that a cluster of galleries is contained within an outer glass skin. But in Toledo the interior rooms themselves are also made of glass. Did that design similarly begin with a desire to mix gallery and circulation space?

KS – In Toledo, we started by trying to avoid circulation entirely. We began with a grid of gallery spaces. Then we looked at how we could open the points of intersection so that different spaces would be directly connected, making one big gallery. All the spaces are made by manipulating this grid. We also tried to make all the interior walls out of glass, so from inside one gallery you can see into others and also outside to the city beyond. But we couldn’t connect everything. We needed buffer zones. The curators wanted to include fabrication facilities so visitors could learn about the process of glassmaking. This process requires a lot of heat, so it needs a buffer zone around it. And then the gallery needs to be an even more stable environment than the buffer zone, to protect the objects.

JR – So you’re layering space not just visually or programmatically but also environmentally to create different climate zones within the building.

KS – And the interesting thing is that the many transparent layers begin to affect the light in different ways, so as you move through the building the glass changes its character, becoming more and more reflective, to the point that you cannot see through it at all. After many layers, even the transparent becomes opaque.

JR – So you can build up opaque boundaries through these strata of glass. It’s almost like you’re creating a horizon, or multiple horizons, within the building—in a sense, you’re actually shaping and separating spaces through effects that at first seem purely visual.

KS – Right, and the different spaces are still related. Each space is always influenced by the space around it.

JR – In both Kanazawa and Toledo, then, thinking about how the visitor moves through the space was a key starting point. Was that also the case with the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York [2007], which you must have been designing at around the same time? That’s a multistory building on an urban site, so movement—at least in the horizontal direction—is very limited.

KS – Yes, the site of the New Museum is very small. The only way to go was up. That means we needed to think about both horizontal and vertical circulation. But at the time we were working on the design, the neighboring buildings were still very low. From the beginning we knew that our building would need to be very high, so we tried to articulate separate volumes and then stack them and shift them as they moved up. This allowed the building to retain a similar scale to its neighbors. The shifting also means that boxes can open on the top or the sides to bring in light or to create terraces.

JR – Did the curators resist any of this?

KS – At first, the curators asked for closed boxes. But we proposed that if the boxes opened, they could start to communicate. Our idea was not only to bring light in but also to allow an exchange between inside and outside. We wanted visitors to enjoy the views, the site, the city all around, and we also wanted to show the public on the street that something is happening inside the museum.

JR – When it came to setting the galleries’ dimensions and proportions, did you have specific works in mind? You must have been facing a similar problem to the one presented by Kanazawa—this museum’s mission is to exhibit the new, which is by definition unknown.

KS – Again, we tried to create a variety of spaces within the museum and, more importantly, many ways you can move through it. Sometimes people can use a stairway along the perimeter, and sometimes they can use the central one. Sometimes the space in front of the elevator is for circulation, and sometimes it becomes incorporated into the gallery. We also tried to think about how it would be possible to divide the space and still have good proportions, whether it’s making one gallery into two or one into seven. So it’s very diverse. But in the end we realized that the curators will still view the space in ways that we did not anticipate—and that’s really interesting.

JR – In all the projects we’ve discussed so far, you seem to maintain a certain distance from the art that will be exhibited in the spaces you designed; you treat it almost as an abstraction. You created containers for art that curators could use in many different ways, and then you focused your own efforts on exploring how visitors can move through and between these spaces. I’d like to ask about your work for Benesse Holdings on the island of Inujima, Japan, where you have been involved with something called the Art House Project. It seems to involve more direct collaboration with artists. How did that begin?

KS – There are many islands in that region, which is in the Seto Inland Sea. The island of Naoshima was the starting point for Benesse, where they built the Chichu Art Museum [2004] and the Benesse House Museum [1992] with Tadao Ando. We designed a ferry terminal there in 2006. And then Benesse asked me to think about Inujima, which was challenging because it’s a remote, tiny island. In the early twentieth century, there was a copper refinery operating on the island, and the population was around three thousand, but now only about thirty people live there. Our client’s idea was to revitalize the remaining village by introducing art projects. Yuko Hasegawa, whom we had worked with on the Kanazawa museum, was the project’s artistic director. There were many empty houses in the village, and we began by thinking about which ones we could transform into galleries. The idea was not to have any permanent works or exhibitions but only a series of temporary installations.

JR – How was that different from designing a museum?

KS – Even in a normal museum—Kanazawa, for example—the exhibitions need to be changed from time to time. But the curators do not want to show that transformation in progress, so as architects we must think of how to hide it, to create behind-the-scenes space that allows these processes to be invisible. In the beginning, at Inujima, we believed that we would have to disguise the transformations, perhaps by altering the pathways people would take around the houses we were changing into galleries. But in a village it’s impossible to hide anything. And eventually we realized that it’s nice to show the transformations: the process of converting a house into a gallery or changing an installation should be exposed. And the people in the village, or the visitors who come to see the project, can enjoy this.

JR – Then the construction becomes part of the work?

KS – And also part of the community. The first thing we did was transform four houses into galleries, and a crew of artists and workers stayed for a month or so to install the inaugural exhibitions. It took maybe ten people to do this, and so for a time the population of the village increased from thirty to forty. But after the opening party and a period of intense activity, they disappeared, and the village was suddenly quiet and sad. So we wanted to make the process more continuous, with people living in the village and artists working and the transformations ongoing.

JR – So the project has become integrated into the daily life of the village. Did that affect your choice of materials and construction techniques? The first galleries were all transformations of traditional houses, correct?

KS – Yes. But even the wooden houses I tried to make transparent, so that visitors can enjoy the art in relation to the existing context. Again, in the beginning Yuko insisted that the galleries should have walls, but eventually she agreed that transparency could work, because this is a very special situation. And the artists can create their installations specifically for these spaces—they know there are no walls.

JR – You also did a transparent pavilion on the island?

KS – Yes, it’s two walls of Plexiglas, and art is installed between them. We started with the houses, but some of them were in such poor condition that they couldn’t be transformed, so I decided to build this pavilion, to create something new. But I realized that the important thing with any construction on this island, new or old, is that it must be made with small pieces. There is no large-scale construction equipment on the island, so even modern materials like Plexiglas or aluminum still need to be brought to the island in small pieces that can be connected by hand. So there will be some continuity, even if the materials are different, between the new and the old, because the construction technique is similar.

JR – It’s interesting that you began by talking about the Kanazawa museum building as functioning like a city, because now you’re describing a literal transformation of a village into a museum.

KS – In our early work, we were very interested in the program of the building, in understanding the social aspects of what happens inside. But now I think the program itself is not as important as connecting the building to the environment, to its surroundings.

JR – Is that a lesson that came specifically from museum design?

KS – I think so. Of course, we are interested in different building types, but we have had many opportunities to think about museums. And a museum is best when it is part of public life.

Excerpt from: Building Culture: Sixteen Architects on How Museums Are Shaping the Future of Art, Architecture, and Public Space by Julian Rose, published by Princeton Architectural Press 2024.