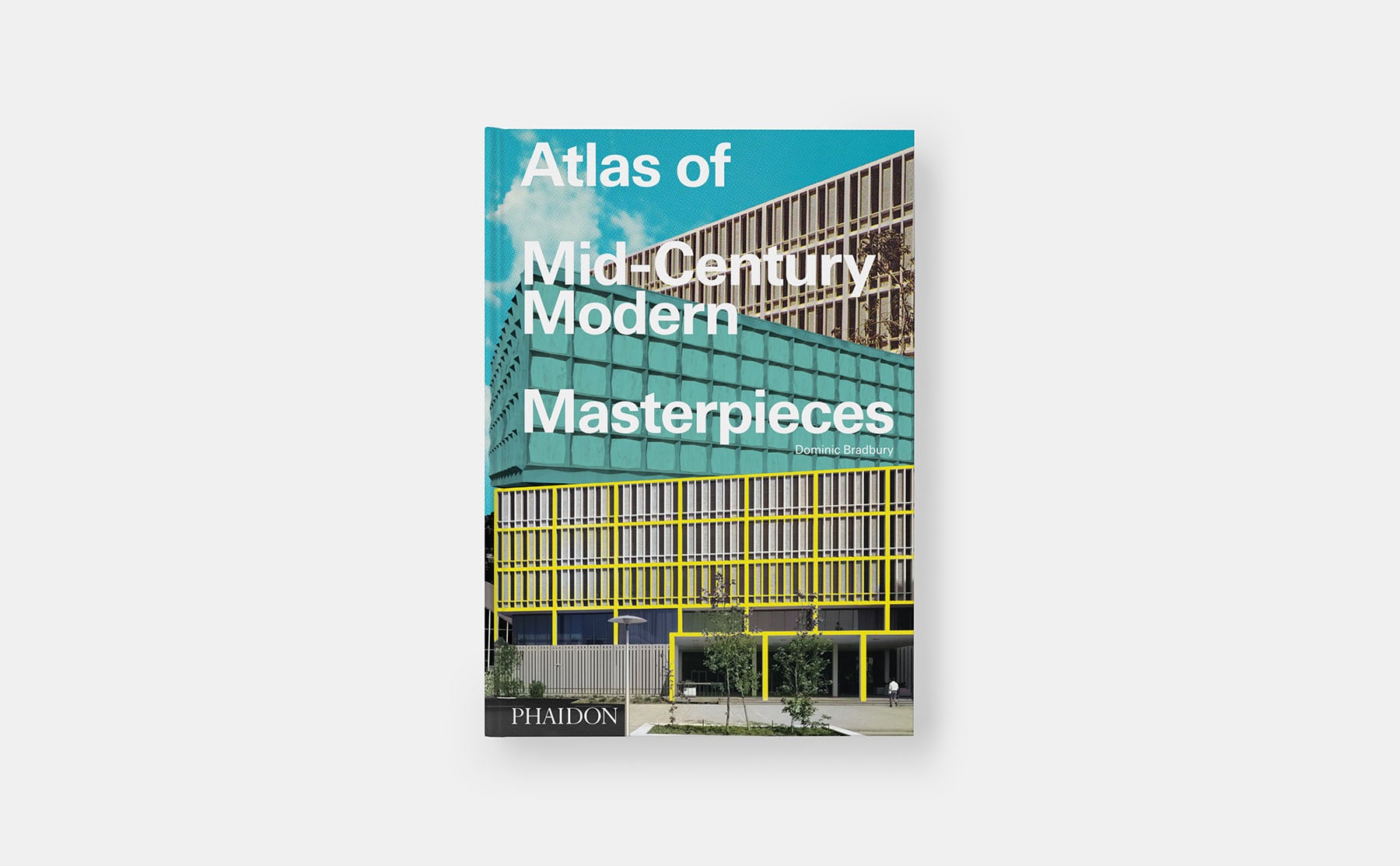

While so many buildings of the mid-century era are now warm and familiar friends, the post-war period still has the capacity to startle and surprise us. This was one of the major lessons of the long research journey that led to the Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces, which is being published this month by Phaidon Press. Encompassing 450 projects from all around the world, the new title features landmarks by the great pioneers of the age such as Eero Saarinen, Gio Ponti, Alvar Aalto and Arne Jacobsen. Yet there are also many less well-known buildings of both beauty and character that help to chart the global evolution of the mid-century style from an optimistic and progressive version of modernism into a radical force for change that was often groundbreaking and experimental.

While many exemplars of the Fifties sit under the welcoming banner of the International Style, which gradually spread its wings across the four corners of the world, from the early Sixties onwards architects increasingly broke free of its conventions in search of something more dynamic, sculptural and expressive. In many cases, such innovation went hand in hand with advanced structural engineering, as was the case with Pier Luigi Nervi in Italy or Félix Candela in Mexico, one of the greatest proponents of super thin concrete shell structures. In Brazil, Oscar Niemeyer famously emerged as the supreme advocate of ‘plastic freedom’, spreading his message of artistic liberation far and wide.

From England to Ethiopia, the mid-century style of the Sixties was eye catching and always engaging, as form-giving increasingly challenged the dominance of the right angle. This was the golden age of free-thinking architectural expression, explored and celebrated across the pages of the new Atlas. Although these buildings might now be fifty years old or over, such radical shape shifting still offers a key source of inspiration for many contemporary architects looking to lift their work above the ordinary and offer something equally imaginative, original and enticing.

NORTH CHRISTIAN CHURCH

Eero Saarinen

Columbus, Indiana, USA, 1963

Following on from the commission to design the Irwin Union Bank (1954), Eero Saarinen returned to Columbus many times over as he embraced fresh commissions of one kind or another for the Miller family and its associated enterprises or initiatives. There was the famous Irwin J. Miller House (1957) on the edge of the city, a glass-sided pavilion that has been compared to the Irwin Union Bank, and then, during the early Sixties, the North Christian Church.

Here, once again, the Miller family played a pivotal part in the evolution of the project. Irwin J. Miller helped to purchase the land for the new building during the late Fifties and was a member of the committee that selected Saarinen, who – by this point – had completed a series of more expressive and experimental projects, which included the TWA Flight Center at Idlewild/JFK Airport (1962).

With the design of the New Christian Church, Saarinen again took a highly inventive approach. The architect had become concerned about the way many modern churches had become multi-functional centres, with a range of ancillary spaces potentially compromising the purity of the sacred space. With this in mind, Saarinen designed an open, hexagonal sanctuary topped by sculptural roof that morphs into a dramatic central pinnacle. An oculus was placed just below the spire and above the altar, with seating then arranged around it. Meeting rooms and the entry sequence were all placed within a gentle berm and positioned beneath the sanctuary, creating a suitably reverential journey upwards and towards the sacred central point.

CHURCH OF ST ANTHONY OF POLANA

Nuno Craveiro Lopes

Maputo, Mozambique, 1962

The architect Nuno Craveiro Lopes (1921-1972) was the son of the twelfth president of Portugal, Francisco Higino Craveiro Lopes, and studied architecture at the Lisbon School of Fine Arts after his military service. During the early Fifties, he was posted to Mozambique, which was then under Portuguese administration, and was appointed head of the Office of Public Works in Maputo (formerly known as Lourenço Marques).

Among Craveiro Lopes’ projects in Mozambique were a small number of churches, most notably the Church of St Anthony of Polana (San António de Polana) in Maputo. Situated in a residential quarter of the city close to the sea, the landmark building is dominated by its extraordinary roof canopy, which has been compared with the shell structures of Mexican master architect and engineer Félix Candela.

The conical concrete canopy has been folded, like a paper crown, multiple times and anchored to a circular base. The sixteen V-shaped apertures and openings where these folds meet the ground become windows and doorways, illuminating the open interior while supplemented by a stained-glass window around the open apex of the canopy. Seating in the round for as many as 600 people is contained within, along with seven altars and a baptismal font.

HAWAII STATE CAPITOL

John Carl Warnecke & Belt, Lemon & Lo

Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, 1969

The San Francisco-based architect John Carl Warnecke (1919–2010) often spoke of the importance of context within his work. For Warnecke, who studied at Harvard University under Walter Gropius, inspiration came from both natural surroundings and urban history, with both playing their part in the design of the Hawaii State Capitol building in the city of Honolulu.

Commissioned by Governor John Burns to host both the Hawaiian Senate and House of Representatives, while replacing the former statehouse nearby, the new Capitol can be seen as a Modernist reinterpretation of the traditional courtyard buildings and dwellings seen in parts of the Pacific region, but executed on an ambitious scale. Yet, at the same time, the new building – designed in association with the Hawaiian practice Belt, Lemon & Lo – is also rich in symbolism.

The central atrium allows the sun and sky to remain visible, while drawing light into the layered walkways and spaces around it. The two legislative assemblies, one to either side, are cone-shaped and intended to represent the volcanoes that brought the islands to life, while the sculpted columns that surround and support the superstructure suggest the palm trees that thrive here, and the series of water pools that surround the building reference the Pacific. Beyond this, there is an intrinsic sense of drama that comes from the way in which the uppermost level of the building cantilevers outward to float over the floors and colonnades beneath. Original and dynamic, the Hawaii State Capitol offers an alternative to the Neo-Classicism common to most statehouses across North America.

FRIEDRICH-EBERT-HALL

Roland Rainer

Ludwigshafen, Germany, 1965

Hard on the heels of the success of the Bremen Municipal Hall (1964), Roland Rainer (1910–2004) turned his attention to the city of Ludwigshafen, which sits on the Rhine directly opposite the neighbouring community of Mannheim and a short distance from Heidelberg. Here, Rainer designed what is – arguably – the most recognizable and distinctive building of his career. As with the Stadthalle in Bremen, the brief called for a multipurpose civic venue and concert hall – here, located in the grounds of Ludwigshafen’s Friedrich Ebert Park – suited to sporting events and concerts. But here, Rainer adopted a very different structural solution, creating a vast concrete gull wing that floats above the open spaces below.

This hyperbolic-paraboloid canopy, resembling a bird in flight, spans 60 metres (almost 200 feet) with the tips of the wings pushing upwards on two sides, while the concrete tip and tail dip down in order to anchor themselves to the ground. The topography around the building was specially adapted to allow for these structural gymnastics, while low-slung service and ancillary spaces push outwards from under the winged superstructure, extending into the park. As with Rainer’s other flexible, mid-century venues, the Friedrich-Ebert-Hall is today still serving many purposes as intended and remains a key focal point for the city.

ST JOHN’S CHURCH

Peter Bosanquet

Hatfield, Hertfordshire, 1960

Peter Bosanquet (1918–2005) studied architecture at Cambridge University and the Architectural Association in London before joining the practice founded by the influential architect, urban planner and author Lionel Brett, later known as Lord Esher. In 1959, Bosanquet established his own practice in Oxford, with projects including commissions for the city’s Ruskin College and two original churches in Hertfordshire – both of which have been listed by Historic England for their architectural significance.

The first of these was St John’s Church in Hatfield, where Lionel Brett had drawn up a masterplan for this new, post-war town. Here, Bosanquet created a distinctive design with a steeply pitched roof, which ascends gently from the entrance towards the altar and sanctuary where the rear wall is almost an A-frame, punctuated by a central cross surrounded by a sequence of miniature stained-glass windows, forming a colourful, graphic pattern. The overall shape of the building has also been compared to an ark.

The gentle tones of the pale, exposed brickwork are complemented by the use of plywood panels for the ceilings, as well as slatted timber around the roof-lights, with the use of such materials lending the church a Nordic sense of warmth. A few years later, in 1963, Bosanquet also completed the Church of St George in Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, with a pointed central spire somewhat reminiscent of Eero Saarinen’s masterful North Christian Church in Columbus, Indiana (1964).

CITY HALL

Arturo Mezzedimi

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1965

During the early Sixties, the Italian-born architect Arturo Mezzedimi (1922–2010) was entrusted by the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie with two key projects in Addis Ababa, which were intended to help encourage the evolution of the modern capital by demonstrating ‘that it is possible to construct grand buildings here too’.

Mezzedimi had followed his father from Tuscany to Ethiopia in 1940 and, from his early twenties onwards, began winning major commissions, starting with the Mingardi Swimming Pool of 1945 and culminating in the twin projects instigated by Selassie – namely, Africa Hall (1961) and City Hall (1965). Africa Hall was completed first, providing conference halls and offices, while ten years later it was substantially extended with United Nations funding to create the United Nations Conference Centre (UNCC) and headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission (UNECA); the building also hosts the UN Economic Commission for Africa.

City Hall was also built on a grand scale and in a central location, initially not just serving as the seat of city government but also providing a cinema, library, theatre and other amenities for the residents of Addis Ababa – all contained within a single complex. The composition was strikingly original, almost forming the shape of a capital A, with two wings projecting outwards to help frame a public plaza and clock tower towards the more open end of the building. Structurally, the building was also innovative, with part of its facade coated in a folded, concertina-like cladding while the central section features a latticed brise-soleil – all adding texture and contrast to the building.

This is an edited excerpt from Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces by Dominic Bradbury, now published by Phaidon and now available for purchase..