Origin stories have long been a staple narrative, going back to the Epic of Gilgamesh. In our current Marvel Cinematic Universe world, origin story production has been supersized. Each member of an army of characters nurtures a painful pourquois that will, at an inopportune time during conflict, burst forth to encumber then ultimately be conquered.

Graphic designers have long imbued their specialty and its star practitioners with superpowers: the ability to be everywhere at once, manipulate and defy time, reshape or create realities, and hypnotic persuasiveness in moving people puppet-like to, usually, consume something. Though only cartoonish, casting graphic designers as heroic may be a film too far. Better Call Saul might be a more apt, tragicomic analogue.

Naturally, it was Steven Heller that spun the intended definitive graphic design origin story in a 1997 Eye magazine article. The title of his spectacle is a spoiler-alert to end all reveals: “Advertising: the Mother of Graphic Design.” While Heller’s view on matters like “ugliness” have seen amendment in succeeding years, he’s held fast to this maternity. In a recent interview with Ruben Pater, Heller stated “I contend that ‘modern’ graphic design was born of advertising. Advertising was born of a need to sell products and make profit.”

Heller’s original pronouncement was prompted by what he considered a perceived disdain for advertising by anonymous practitioners. “The word ‘advertising,’ like ‘commercial art,’ makes graphic designers cringe,” he asserts in his opening sentence. I’ll spot him the wide-spread reaction to the “commercial art” appellation but who are these anonymous, effete snobs about advertising? Considering the article’s mid-90s origin, his broadside seems another preemptive strike at critics of Modernist verities dear to Heller. He could also have perceived advertising antagony among designers as throwing shade at Paul Rand, who made his name as an ad man. Elevate advertising to progenitor and then all graphic design can run through Rand.

A cursory glance at current and past designerscapes will reveal a different type of twitch about advertising: all readily apparent evidence attests that graphic design is in thrall and devoted to advertising. Far from scorning the link, designers assiduously polish the chain binding the activities to each other. I’ve taught with colleagues that regarded a design purpose outside of advertising as crazy talk. Students spontaneously speak of graphic design as a selling proposition. Spring brings the annual panoply of social media posts of practitioners and academics—most much younger than me—proudly flaunting awards for their or students’ work from advertising competitions.

Whatever Heller witnessed was selectively observed, limited in scope, and unrepresentative. While his prompt may be off base, on the surface the argument he musters for advertising as graphic design’s procreator appears iron-clad. There certainly is no shortage of fellow adherents and advertising material to back him up. The sheer volume of graphic design matter generated by advertising seems an overwhelming proof. If you accept that graphic design’s near-exclusive prompt is profit-generation via sales of goods, the conclusion about its parentage is guaranteed. What else is there? Reflexively, most designers and non-designers will agree with the supposition. Sales permeate our world. It’s a de facto assumption; a preordained premise.

Heller marshals a few key historical sources from the early 20th century to support his thesis. These are graphic design’s formative years, where it establishes itself as an autonomous activity, separate from print production. To corroborate an advertising/graphic design lineage, Heller invokes design polymath William Addison Dwiggins for having coined the term “graphic design” in 1922. He then quotes from Dwiggins’ 1928 book Layout in Advertising: “for purposes of argument ‘advertising’ means every conceivable printed means for selling anything.” From these two facts, Heller concludes “This suggests that advertising is the mother of almost all graphic design endeavor, except for books and certain journals.”

Does it? (And is advertising, “books and certain journals” all there is to graphic design?) The implication is that Dwiggins and Heller are simpatico. However, placing points in proximity doesn’t create a causality. Heller is engaged in some sleight of word, slipping in his own definition of graphic design as an activity for “selling things” and assigning it also to Dwiggins. That Dwiggins agreed isn’t evident from these statements. A direct interpretation is that Dwiggins was simply setting the terms of what Layout in Advertising would cover, not assaying an overarching definition. How else to read “for the purposes of argument” than as Dwiggins stating his definition is provisional?

Meanwhile, a fundamental error lies at the center of Heller’s theory. Paul Shaw has convincingly established that use of the term “graphic design” predates Dwiggins by half a decade. Heller popularized Dwiggins as coiner of the term, largely through the republication of WAD’s 1923 article “New Kind of Printing Calls for New Design” in Looking Closer 3: Classic Writings on Graphic Design. But in lengthy, scrupulously sourced posts debunking Dwiggins as birther of “graphic design,” Shaw indicates that Heller’s misinterpretation runs deeper than myopia on dates: “(Heller’s) introduction to ‘New Kind of Printing Calls for New Design’ is not only marred by several factual errors, but it fails to understand the context in which Dwiggins’ essay was written as well as its full significance. (Heller) writes, ‘Before William Addison Dwiggins (1880–1957) introduced the term ‘graphic design,’ descriptions like ‘printing art,’ ‘commercial art,’ ‘graphic art,’ and ‘advertising design’ were used interchangeably to connote the visual output of the advertising profession.” This is not entirely true, as ‘printing art,’ ‘commercial art,’ and ‘graphic art’ often referred to illustrations created for books and magazines, rather than solely for advertising purposes. The various terms that Heller cites were not interchangeable. Definitions of each varied from commentator to commentator and changed over time from the Arts & Crafts era to the 1920s.”

Another oversight is that in the sentence that supposedly introduced “graphic design” into the lexicon, Dwiggins bluntly states advertising is a component or aspect of graphic design: “Advertising design is the only form of graphic design that gets home to everybody.” Clearly, Dwiggins considered graphic design to be a broad field of activity that encompassed advertising. To contend he exalted advertising is to invert Dwiggins’ plain words.

Heller also showers accolades on Ernest Elmo Calkins for introducing Modern Art into advertising in the 1930s. Is this anything to celebrate? Calkins discards all the social principles vital to the European Moderns’ crusade. Design is reduced to an empty formal exercise that only gestures toward modern ideals. Advertising here resembles less a parent than a parasite. It isn’t life-giving but substance-draining of the host; a surface treatment, maybe a melanoma. It’s debatable if exposure to Calkins’ limp, derivative tropes of Modern Art led American audiences to an appreciation of the sharp, original expressions. What American advertising inarguably did was offer consumerism as the means to modernity.

Other examples fare no better when scrutinized. Heller highlights Kurt Schwitters’ and Jan Tschichold’s role in “Der Ring Neue Werbegestalter”—“The Ring of Modern Advertising Designers.” This “Ring,” or “Circle,” bore no resemblance to any advertising firm before, at the time, or later. The Ring didn’t take on clients and craft campaigns. But it did have a letterhead as a “real” company should. The Ring exhibited pre-existing work that was simply graphic design in the public sphere.

The association’s purpose wasn’t to hawk wares but advance the ideas of the new typography. In its brief, three-year lifetime the association counted some two-dozen “members” across Europe, most of whose involvement consisted of inclusion in one of the group’s 23 exhibitions. The Ring didn’t produce work, it collated. Though not an advertising firm in any sense of the term, the Ring does show that lacking the term “graphic design,” practitioners defaulted to calling work “advertising.” The ideals of the Moderns—the impulse for their efforts—were of broad progress, access, and self-determination for the people. It wasn’t “the adman!” that Tschichold held up as exemplar in the introduction to Die Neue Typographie. That book was first a capabilities brochure for a new body politic through design—not about ably moving merch.

More importantly, the simple problem is that Heller’s “modern” graphic design had been “born” before Calkins—and in ads. Though not as widespread as Calkins’ products and almost indistinguishable from the “editorial” content, Schwitters included Pelikan ink promos in the “Reklame” issue of his magazine Merz. Heller credits the replicants while dismissing the originals. In his own article, Heller notes the primacy of graphic design but skips over it: “As the modern movements sought to redefine the place of art and the role of the artist in society, advertising was seen not only as a medium ripe for reform, but also as a platform on which the graphic symbols of reform could be paraded along with the product being sold.”

Those “graphic symbols of reform” were graphic design. The purpose of reforming advertising wasn’t to efficiently flog products but to have a unified, graphic revolution to spur and reflect a restructured, classless social order. In his introduction to the English language edition of Die Neue Typographie, Robin Kinross points out “…the intimate association between modernism in design and socialist politics is clear— or, at least, the connection was clear in that time and place. Both strands combined in a single outlook that might typically be termed ‘progressive.’”

It was revolutionary reform—of language, of representation, of society, of life—that was foremost on these designers’ minds. Here is the true “mother” of graphic design, residing out in the open, readily identifiable. Graphic design as we know it was initiated and nurtured as activism: progressive, political speech.

It’s often remarked how some example of political graphics makes use of or emulates the devices of advertising. This is decidedly backwards. Advertising’s methods and strategies were first employed in the work of pioneering designers such as John Heartsfield. His technique of photo-montage reaches further than political graphics.

Graphic design wasn’t merely a vehicle for speech, it was speech. If money can be “speech” (or so says the Supreme Court), why not design? Graphic design embodied the purposes, forms, and technology of the day in the attempt to transform society, communicate widely, and tear down barriers between people. As a communication form, graphic design was seen as immediate, accessible, and pervasive.

Graphic design provided literal substance for ideas. The Moderns began the phenomena of self-declared art movements: Futurism, Suprematism, dada, Surrealism, and more were announcements to the world of cultural causes. These pronouncements gained authority through graphic design in distributed manifestos and correspondence on bespoke stationery. Plus, they generated pamphlets, posters and various printed ephemera. All of which were graphic design productions not merely for efficiency or convenience but for what the medium represented.How has this history been overlooked or downplayed? Why can’t—or doesn’t—graphic design recognize and acknowledge its own “mother”?

Modernist designers adhered to those utopian/progressive ideals to varying degrees. Some fled Europe to settle into the welcoming, lucrative arms of U.S. multinational corporations. Corporate embrace of their form language served to distribute their standards globally. Simply employing proper form was considered virtuous. Having fashioned an identity based on serving business, design wedded itself to the idea it was spawned of sales. It doesn’t know where else to look. Graphic design’s well-heeled step-parent usurps the role as sole relative. Then with the blinding light of capitalism, he inescapable glare of consumer culture is simply overwhelming.

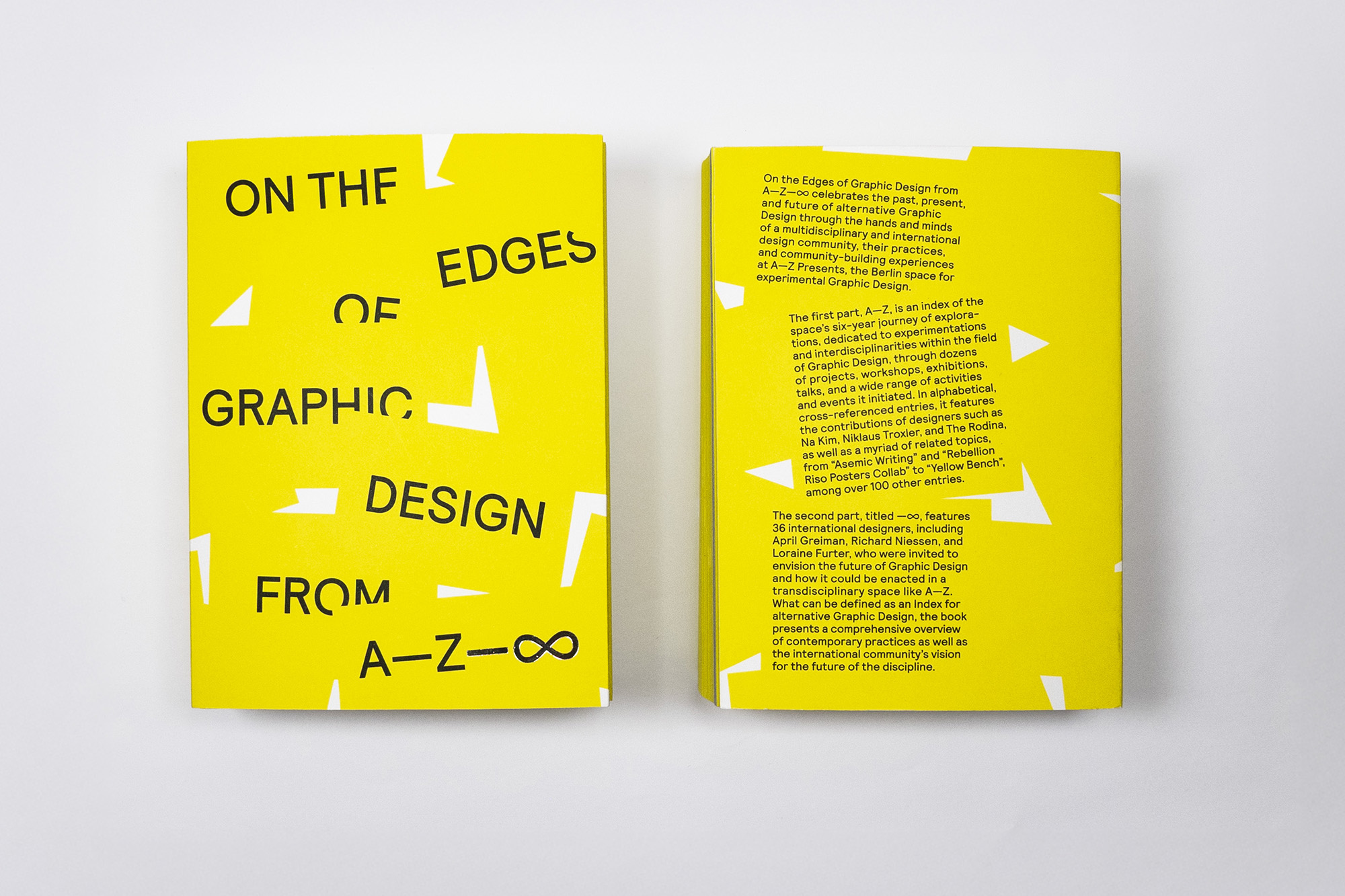

In the prevailing view, practicing graphic design to facilitate others’ earnings is all that matters. Activity differing from commercial intent doesn’t even exist or is “outside.” This was the dismissive criticism leveled against the exploratory design of the 90s: that it was meaningless due to it being non-commercial. But expand design into a discipline and the profit motive becomes only one impetus for design activity.

How should the status of graphic design’s “mother” be determined? Ubiquity? Influence? Capitalism might not be bested on omnipresence, depending on what we look for or at. Perhaps it should be the action that shows a commitment to graphic design. Something that brings people to make design themselves, where they have a personal relationship with the form. The most open and enduring public graphic expression is hand-crafted signs supporting and decrying social, cultural, and political issues. Here we always find everyday people performing graphic design, having a direct, intimate connection with the practice.

This design is often awkward, derivative, and raucous; eschewing niceties of discourse and aesthetics. It’s also direct, vibrant and immediate. The playing field dominated by advertising gets evened when you include these works as graphic design. But because these pieces aren’t the product of capital it’s typically discounted. It may not be adding to graphic design’s formal evolution—many professionals would say it detracts—but it’s reinforcing design’s social role.

At times of social ferment, design groups have spontaneously formed not for profit but to support political stances. Their lifetimes are often short but energetic. But advocacy design is not solely the province of the amateur. Numerous professionals and businesses have dedicated themselves to advocacy design with as much verve and capacity as performed for pay. And sometimes they overlap. There are the iconic “I am a man” placards, produced by professional print shops. Or the work of Emory Douglas for The Black Panther.

Advertising as the mother of graphic design is ultimately pessimistic about human nature and the drive to perform design. It isn’t a base motive to recognize the need to make a living and to do so through performing graphic design. It’s reality. The problem is building an identity solely on and championing only sales.

Fortunately, there are critical voices providing a more diverse and inclusive motive for graphic design. Or, that claim a different hierarchy. A design history text that acknowledges the role and force of progressive speech in the story of graphic design is Stephen Eskilson’s Graphic Design: A New History. “The costs of the Industrial Revolution incited printed criticisms from Marx and Engels to Daumeier,” Eskilson writes in his introduction, “While these varying attempts at social change through design often seem to have only a minor impact on the world at large, the concept of design as catalyzing, beneficent force for social change is one that has endured to the present day.”

Richard Hollis begins his book Graphic Design in The Twentieth Century (formerly Graphic Design: A Concise History) outlining “three basic functions of graphics…The primary role of graphic design is to identify: to say what something is, or where it came from…Its second function, known in the profession as Information Design, is to inform and instruct…Its third role, very different from the other two, is to present and promote…” This third role is where Hollis mentions “(posters, advertisements).”

Ruben Pater’s Caps Lock: How Capitalism Took Hold Of Graphic Design, at first seems to roughly align with Heller that graphic design sprouted from capitalist roots, noting, “The oldest messages ever found are not diaries or love poems, but financial records,” and “Financial records are clear examples of early graphic design.” However, along with indicting graphic design for marketing capitalism, Pater proposes an alternative ancestry for the practice. In “The Designer as Engineer,” he describes the oldest known map, a 14,000-year-old carved stone found in Spain. “That would suggest that early forms of graphic design such as sign-making and mapmaking were around long before anything resembling capitalism existed.”

At the same time, many graphic designers continue to seek and advocate for a definition of their practice that isn’t rooted in sales. The regular restatements of the “First Things First” manifesto is testament to a constant, clear-eyed desire for design to mean more.

Heller concludes his article with an appeal for clarity: “During the past decade there have been calls to develop new narratives and to readdress graphic design history through feminist, ethical, racial, post-colonist, post-structuralist and numerous politically correct perspectives. There are many ways to slice a pie, but before unveiling too many subtexts, it is perhaps first useful to reconcile a mother and her child.” It’s useful only if it’s accurate. That “past decade” began some 40 years ago. Since that time, those “politically correct” “new narratives” have revealed themselves to not be subtexts but texts. Advertising is but one of many slices, certainly an out-sized one in stock estimations. A graphic design history that doesn’t address the influence of advertising isn’t telling the whole story. But it’s not the only story, or even the first. Advertising has been, at best, in loco parentis of graphic design. But “mother”? ¡ni loco!