Archives affect people’s collective memories and relationships with the past, present, and future. They are time capsules to what has come before, resources for those seeking to find out more, and a tool for storytelling. Archives allow us to contextualize ourselves as individuals, groups, and societies historically, helping us shape ourselves in the current moment and think about what comes next.

Archives have historically been overseen by institutions. Often materials in the archive were dictated by a curator, who goes through the process of selecting information that is deemed most useful and relevant. Although this process is meant to be impartial, there is a level of subjectivity and bias in what is deemed important or archivable when one person or a small group of people are making selections on behalf of the public. When the power to choose how groups and communities are represented in archives is given to a select few, it invites the possibility for misrepresentation, or worse: erasure in and from the archives, which affects the way people see themselves living and existing in the world. The public should be invited to share their histories, perspectives, and voices.

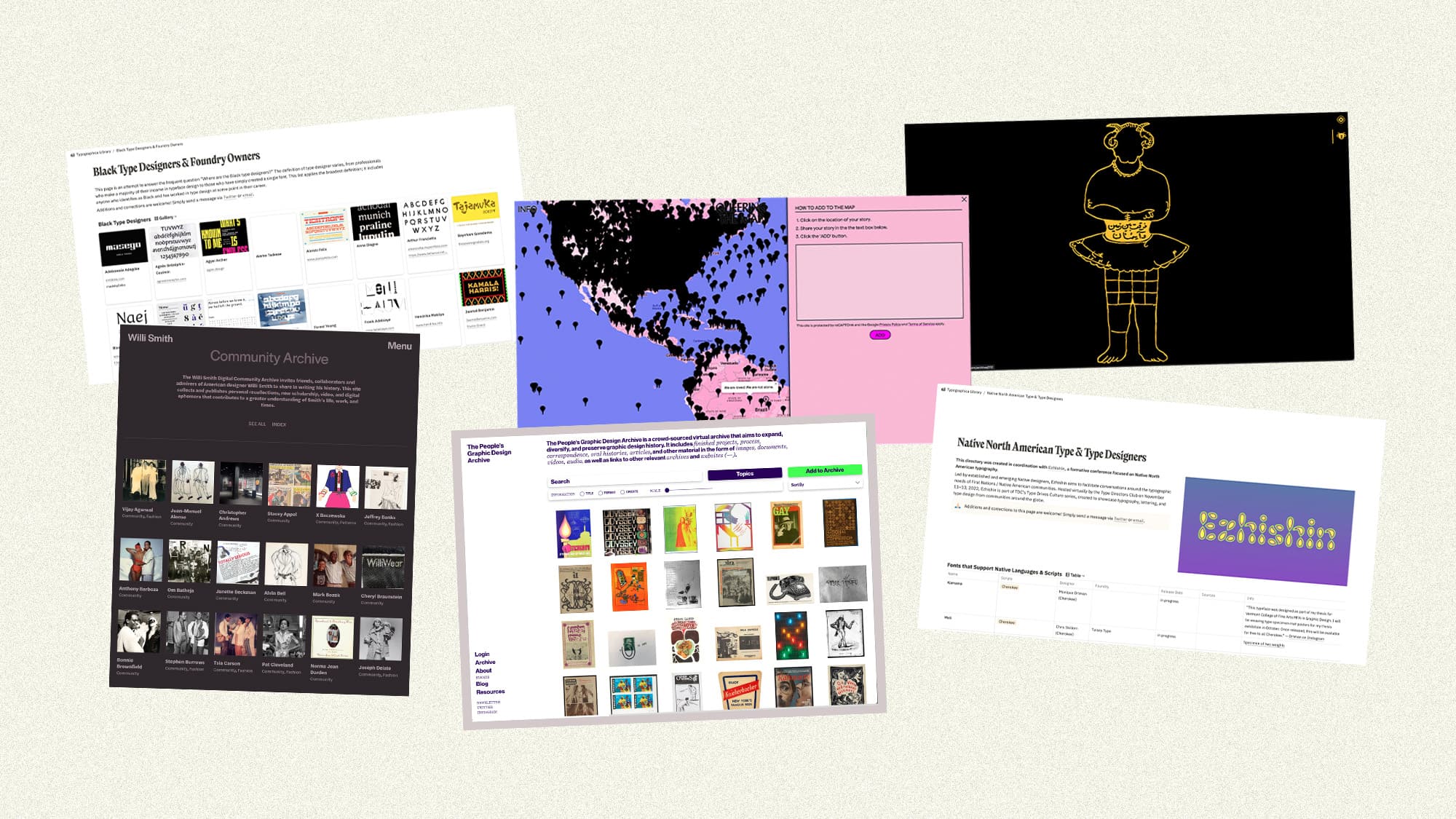

The internet has allowed archives to become something that can be created and preserved, collectively. Online, everything is archived, and everyone is an archivist. Without digital archives, the public would not readily have access to any of this information, or the ability to contribute to them. The affordances of technology allow communities to rethink and reshape what archives are and can be, leading to new methods for creating archives. In response to community needs, community archives are an activist approach that goes against the grain of what has traditionally been the practice of managing an archive. Digital tools allow many new voices to act and assert agency, and digital community archives prioritize accessibility and inclusivity.

What are alternative archival practices that challenge institutional norms? What makes an archive inclusive for communities and their members? How does the design of an archive influence the way it’s organized, maintained, and shaped? Who gets to decide what is in an archive, and how people can access its materials, and interact with it? The examples of digital community archives we offer are contemporary projects that answer these questions by challenging assumptions and norms of archival practices.

How can archives rewrite dominant narratives about a collective past for voices that have been marginalized and oppressed?

The People’s Graphic Design Archive is a crowd-sourced virtual archive that aims to rewrite the dominant narrative of graphic design history by relying on community participation and contributions of design artifacts that create an expanded view of design history. The community archive is molded by its members as they document, record, explore, and restore history. The site hosts educational resources that help make contributing accessible to anyone. These resources include tutorials on adding to the archive, documenting work, conducting interviews, tagging, and how to teach with the archives. PGDA, which launched in 2020 as a Notion page, now has a new permanent website that went live on September 1st, 2022. On the new site, contributors create an account that archives their submissions under the “all my items” page, essentially creating an archive within an archive. By archiving submissions under a contributor’s name that is viewable by all visitors of the site, it becomes a place for individuals in the community to connect with each other. The framework for how PGDA functions fosters an inclusive archive for its members and the design community by inviting anyone to be an archivist and offering an alternative to traditional practices by being transparent about who is authoring the site. “We’re coming up with these different kinds of instruments to encourage people to make it [archiving] festive,” Louise Sandhaus told Print Magazine. “and to concentrate on areas of design that a community wants to see more representation of in the archive.”

How can archives uplift those who have historically been under-represented?

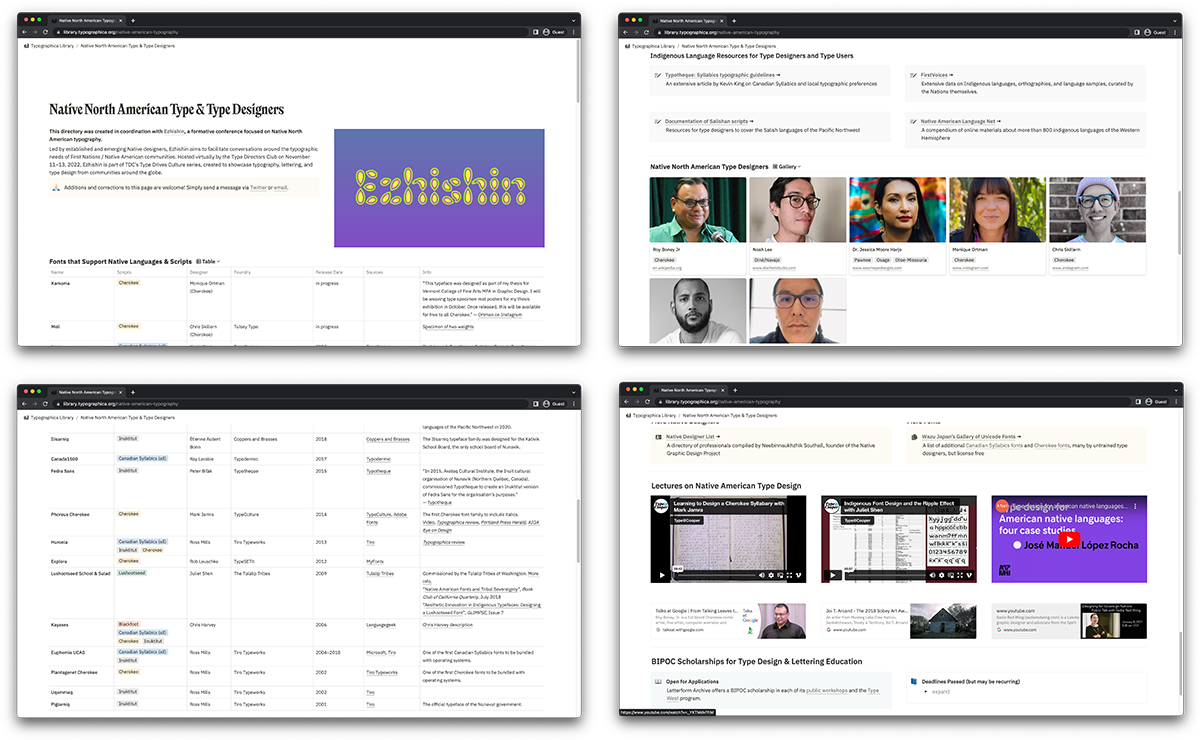

The People’s Graphic Design Archive is a broad response to the landscape of graphic design history, but we also see community archives emerging that answer more specific questions. In 2017, Bobby C. Martin Jr. asked the question “Where are all of the Black type designers?” at the TypeCon conference in Boston. In 2020, during the Black Lives Matter uprisings and protests, this question took on a new urgency, leading to a twitter thread where individuals tweeted about Black type designers that they knew. The thread was aggregated to form the basis of the Black Type Designers & Foundry Owners archive created by Typographica. The archive serves as a tool and resource for those who are looking for Black designers, which continues to evolve and expand through the input of the community. It now serves as a resource for finding BIPOC type design scholarships and lists that promote the visibility of Black designers, studio owners, and printmakers. Native North American Type & Type Designers is the newest archive created by Typographica in coordination with Ezhishin, a conference focused on Native North American typography. Using open-source platforms like Notion, these resources uplift designers and creatives that have not typically been represented in the design field’s Eurocentric canon.

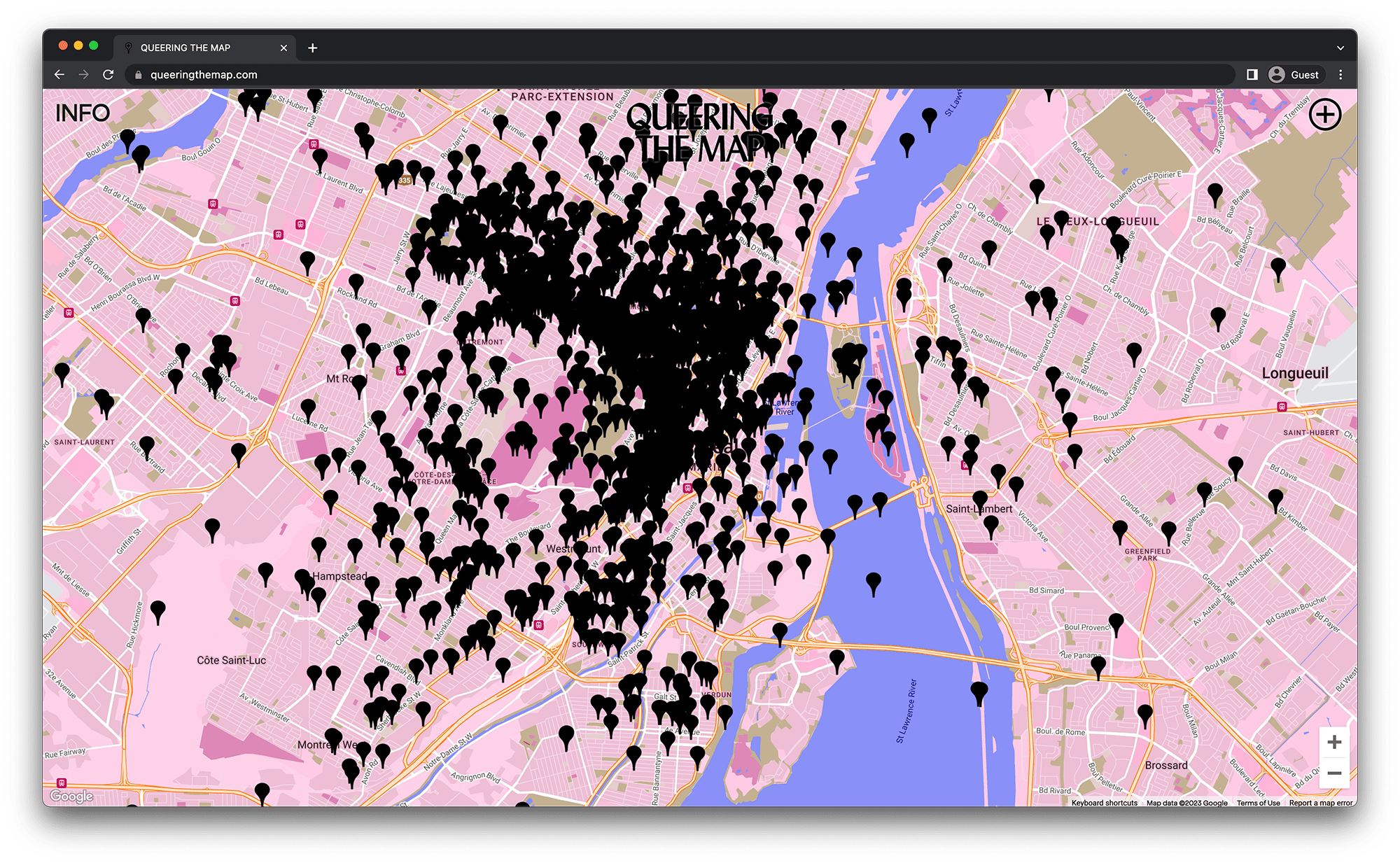

Created and designed by Lucas LaRochelle.

Can an archive create a sense of community when its contributors are anonymous?

While the Black & Native American Type Designers list ensures that certain members of a community are being uplifted, other projects such as Queering the Map project and Willi Smith Community Archive ask communities to represent themselves through expanded interactions such as commenting, tagging, and adding of personal histories, narratives, and points of views that directly influence the way they are organized, maintained, and shaped. Queering the Map is a community-generated archive that creates a safe digital space for people to share their LGBTQ2IA+ stories anonymously in relation to a geographical location and space. Queering the Map is fully reliant on its contributors to create the database of queer stories, aggregating a living account of queer life and love; from stories about someone’s reckoning of their sexuality at a concert to the first time they met their partner in the middle of the sea, these personal stories go beyond geographical borders to show us how intimately connected we all are. It has also turned into an ad-hoc way of commenting and communicating through anonymous messaging, creating a space where others uplift each other through supportive and encouraging messages. Queering the map shows what is possible when creators of an archive design the platform in a way that allows visitors the opportunity to contribute their own content, and for that content to become the archive. “[Queering the Map] facilitates such relationships, or what I call an act a queer ethics of care, towards the story shared on it through this dis-organizational strategy that favors the multivalent, the opaque, and the imperfect…,” Lucas LaRochelle, the platform’s creator, said in a talk at the Guggenheim Museum. “I don’t want to theorize on them as much as I want to theorize with or alongside them. They are themselves chunks of theory in the form of an experience. I ultimately want to be in the world with them.” The stories shared on the platform become more than just a narrative, but rather an act of resistance to preserve the collective memory of queer and trans love. The design of the website allows for collaborative cartographic mapping of queer experiences, to amplify multiple voices within the queer community and preserve queer histories which are constantly being attacked and erased.

How can a community archive tell a contextualized story?

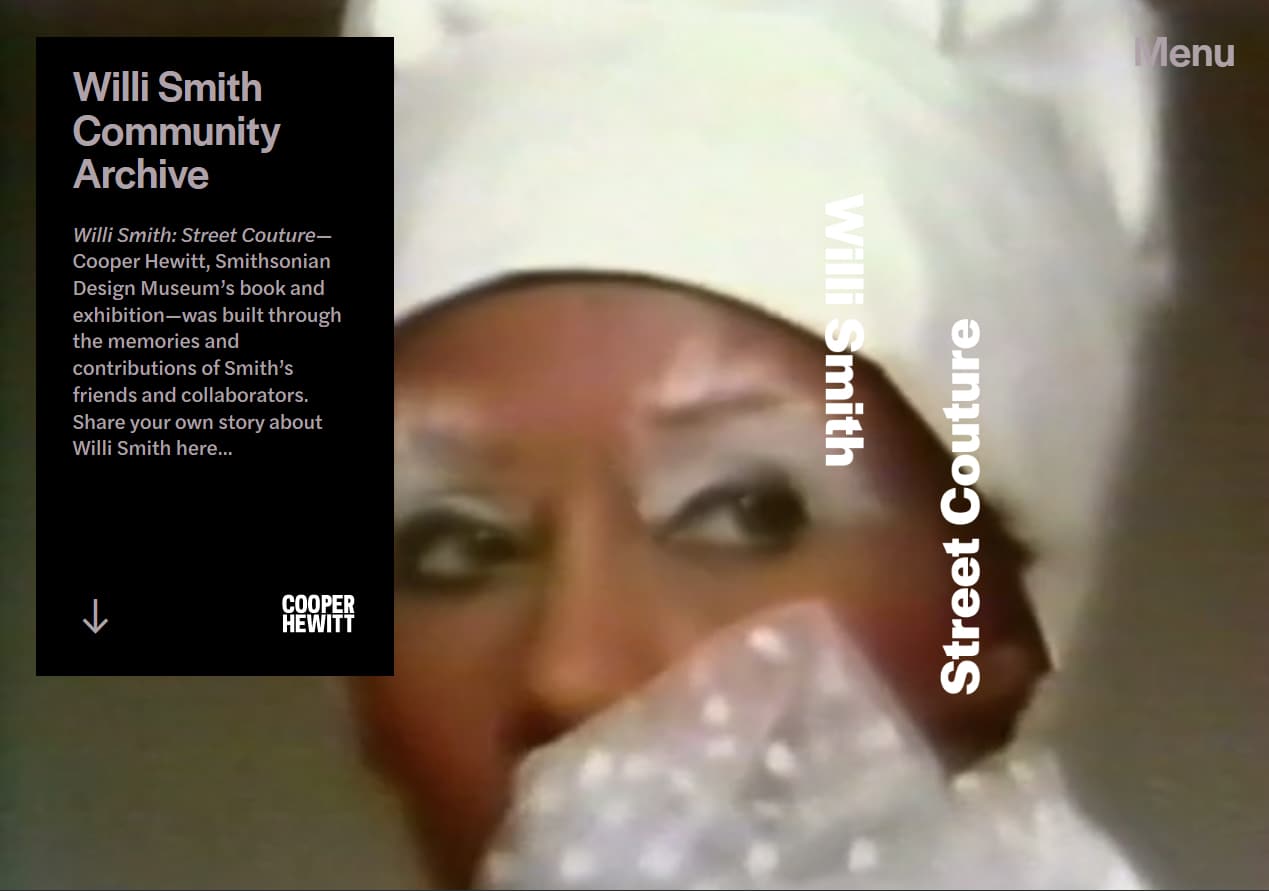

Rather than taking anonymous contributions, the Willi Smith Community Archive invites friends, collaborators, and admirers of the fashion designer to share in writing his history and story. The community archive — which was organized by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum on the occasion of a related exhibition — has a wide range of stories from personal recollections to videos that give us a greater understanding of Willi Smith’s personal life and work. By initiating this, the Smithsonian, a traditional institution, is perhaps subverting its own archive by opening it up to the public to contribute. While the information presented may not be validated or vetted by traditional institutional standards, the archive values the lived experience of the public and those closest to Willi to tell a more contextualized story. The Willi Smith Community Archive is an example of how to validate the histories, experiences, and collective memory of a community to expand the documentation and illuminate the rich histories of people whose lives have not been traditionally documented, told, or studied. The community archive “illustrates how practices of documentation as a canon must be examined and reinterpreted so as to archive the lives and work of those not typically chronicled. Documentary approaches such as the Community Archive offer an alternative and more inclusive means to measure an individual’s cultural impact,” wrote Charlotte von Hardenburgh in Objective Issue 5. The design of the Willi Smith Community Archive goes against traditional archival formats by showcasing collective storytelling; a multi-dimensional approach to weaving together several voices to tell the story of one person.

Can a community archive exist without community contributions?

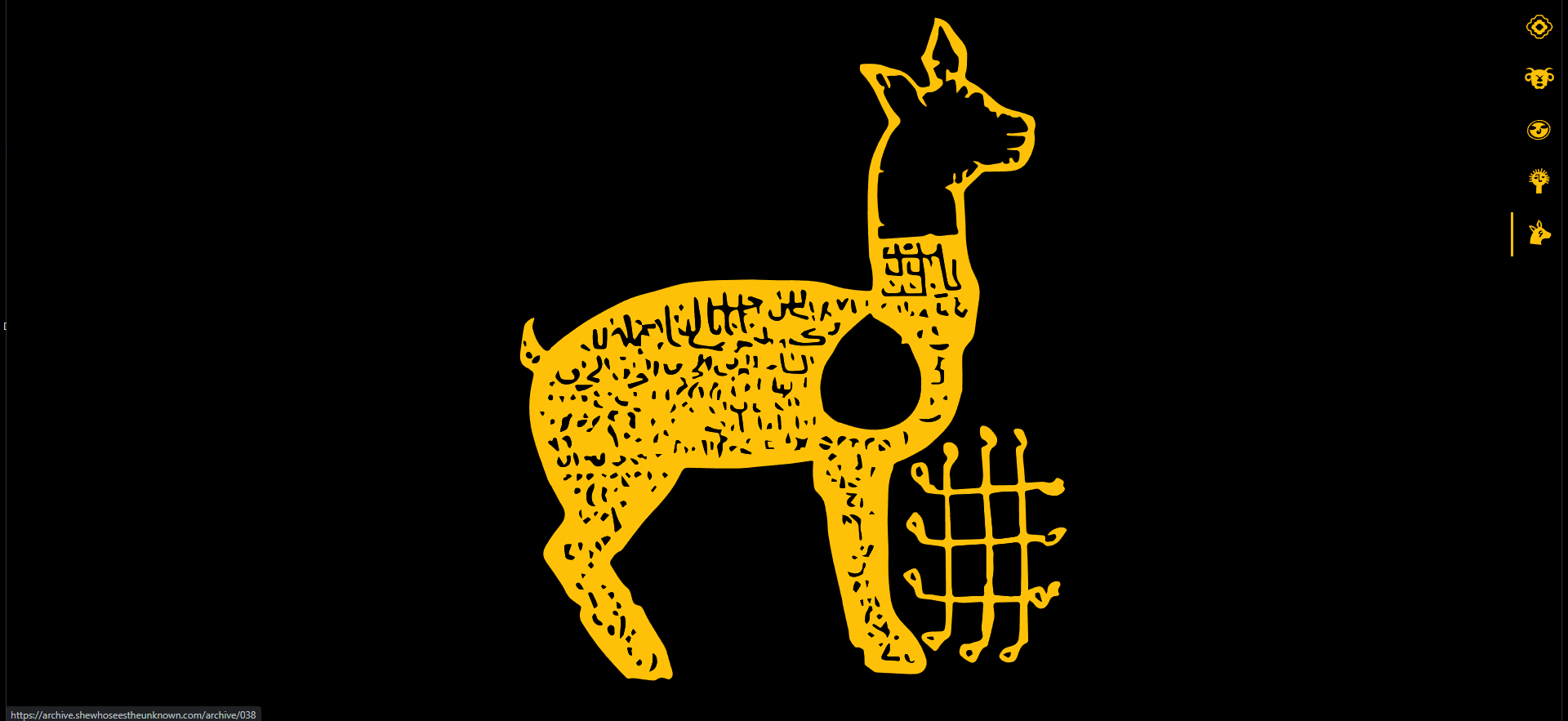

Like the Willi Smith Community Archive, She Who Sees the Unknown: The Archive brings a renewed understanding and representation of historical cultural figures. The archive uses storytelling to challenge monstrous figures of Middle Eastern origin as an act of preservation and activation. The creator of the archive, Morehshin Allahyari, considers this a practice of “Re-Figuring” forgotten figures and re-situating their histories. There are four layers in the archive, the first layer is accessible to English speakers, but to pass through to the next layers the visitor must be able to answer a set of language and cultural codes that preserve access to Arabic and Persian-speaking people. She Who Sees the Unknown becomes a gamified archive that asks the user for passcodes for entry into the stories that represent and shape cultural heritage in the SWANA region, protecting the information in the process. Moreshshin considers this an activist practice that reflects on the effects of historical and digital colonialism and other forms of oppression. She subverts what it means to create barriers to an archive, by safekeeping its information for the community it aims to represent. In an interview with Eyebeam, Morehshin shares “I worked on the archival aspect of this project while continuing to question digital colonialism and how we can give access to knowledge while also protecting it from colonial powers.”

Created and designed by Morehshin Allahyari as part of her research

Looking at these examples, there’s an explicit relationship between how an archive is designed and the content that gets archived. There is no set of rules, procedures, or protocols that must be followed to create a community archive, it is purely a response to what a community needs and wants to see represented. By expanding who can add to an archive and what gets added, community archives show a complex, multi-faceted, and multi-layered understanding of archiving. Inclusive community archives empower individuals and communities who have often been marginalized from archival spaces to reclaim space for themselves. The shaping of these archives is fluid, organic, and free forming, informed by collective memory and knowledge. By sharing their experiences and narratives communities get to represent themselves in history. This radical approach to archiving contributes to our representational belonging, allowing communities to discover themselves in the archive and see themselves as existing in the past, present, and future.