This interview is excerpted from With Dilemmas From the Future: What can graphic designers do in the era of climate crisis? by Minami Hirayama and is available to purchase here.

This book project started from my dilemma of being a graphic designer and environmental activist. We graphic designers often create something to be consumed more and faster, so that companies can make an ever-growing profit. On the other hand, the state of the planet is deteriorating at speed from climate change which is caused by the extreme form of capitalism. I felt a strong urge to investigate if I could avoid being fuel for climate catastrophe while carrying on doing graphic design.

Luckily, I found multiple designers who are already trying something different and creating a positive impact in relation to climate change. I interviewed five designers and one printer in the book. They told me different ways of approaching the topic and provided various ideas of “What we can do”. In this article, I will share the interview with one of the interviewees, Benedetta Crippa.

Benedetta Crippa is a graphic designer and researcher based in Stockholm, Sweden – originally from Italy. While she works as a lead designer of the Stockholm Environment Institute, she also teaches at Konstfack University about “Visual Sustainability”. She points out the importance of looking at our current systemic problem to think about sustainability.

You started working as a lead designer at Stockholm Environment Institute in 2018, could you tell us how you found yourself in this position along with your own design practice and teaching job? What do you find exciting or challenging in working at this institute?

I was fresh out of graduation from my second MFA when I applied for the position at SEI. Colleague Brita Lindvall Leitmann told me about the advert, which would have otherwise escaped my attention. It is so important with more senior colleagues tipping us about jobs and encouraging us to apply, especially amongst women, and I am grateful to Brita for that. Getting this job was also a reminder to keep on applying for opportunities. Like many women, I probably would have not applied if I knew I would compete against 150 other people. But I did not know and instead did my best through a thorough, well-structured recruitment process, and got the position as the very first graphic designer in the 30-year history of the organization.

At the time I just opened my own studio, and the position at SEI meant that I could work within an established institute very much aligned with my own values, as well as gaining extra safety in a moment when I was starting up. I was lucky to land within a community of extremely talented and dedicated people with high integrity. Working at SEI means being constantly reminded of how many people are actively engaged making this world a better place, something we may forget about when we are so flooded with negative and destructive information. So I sleep better at night because of that. And I am proud to be supporting them in this through my own craft. The flexible working schedule, more and more part of the Swedish working mentality, allows me to fully manage the job amongst other commitments.

The most refreshing aspect for me is the international environment, I can be in meetings with colleagues from 7 different countries at once, something that in Sweden is still very rare if not unique. Cultural diversity for me is key to maintaining a sense of perspective and humbleness through existence. The challenges are the ones typical of the social equity and scientific sectors: most people working in these fields are overworked and underpaid, which leads to fragmentation and lack of tangible rewards; and the job requires constant and immense efforts of capacity building, to establish a mindset around design first and foremost. The scientific field at large still thinks about visual communication as a nice package for its work, rather than something that actually tears down barriers between the work, and who it should reach. But as the field also reckons with its apparent failure to successfully communicate the magnitude of the climate crisis, things are changing, rapidly. More and more organizations and companies invested in sustainability, science and social equity are hiring in-house designers or establishing ongoing collaborations with design consultants. I am expecting this to increase exponentially in the next 10 years.

Could you tell us about the course you teach at Konstfack University called “Quantum Thinking: Sustainability in and Through Visuality”? What does “Visual Sustainability” mean?

The course was born out of the realization that the discourse around sustainability within design was rapidly degenerating toward the idea that sustainability must equal an extreme reductionism in form. Unsurprisingly, this has been the dominant norm in terms of aesthetics for the past century. As someone committed to visual harmony and aware of the transformative power of beauty, this deeply concerned me. Designing sustainably was becoming designing less, or possibly not designing at all, and a general disregard was raising toward the opportunities of form to contribute to sustainable practices. We are raising and graduating a generation of designers that feels guilty about designing. We are an easy target, but this is a destructive and fundamentally misleading approach to sustainability and I wanted to provide a counter-argument.

The main aim of the course is to break down such myths, expose where they come from, and introduce a more holistic perspective on how form can challenge systemic power and exploitative practices. I find that students are relieved, and once they reframe their way of thinking about sustainability (it takes some effort after years of conditioning), they finish the course with a renewed energy and sense of purpose about their craft and their role in society.

“Visual sustainability” was the term I identified as best to describe sustainability achieved through visual work. It works well to put the emphasis on the effects that form in itself carries.

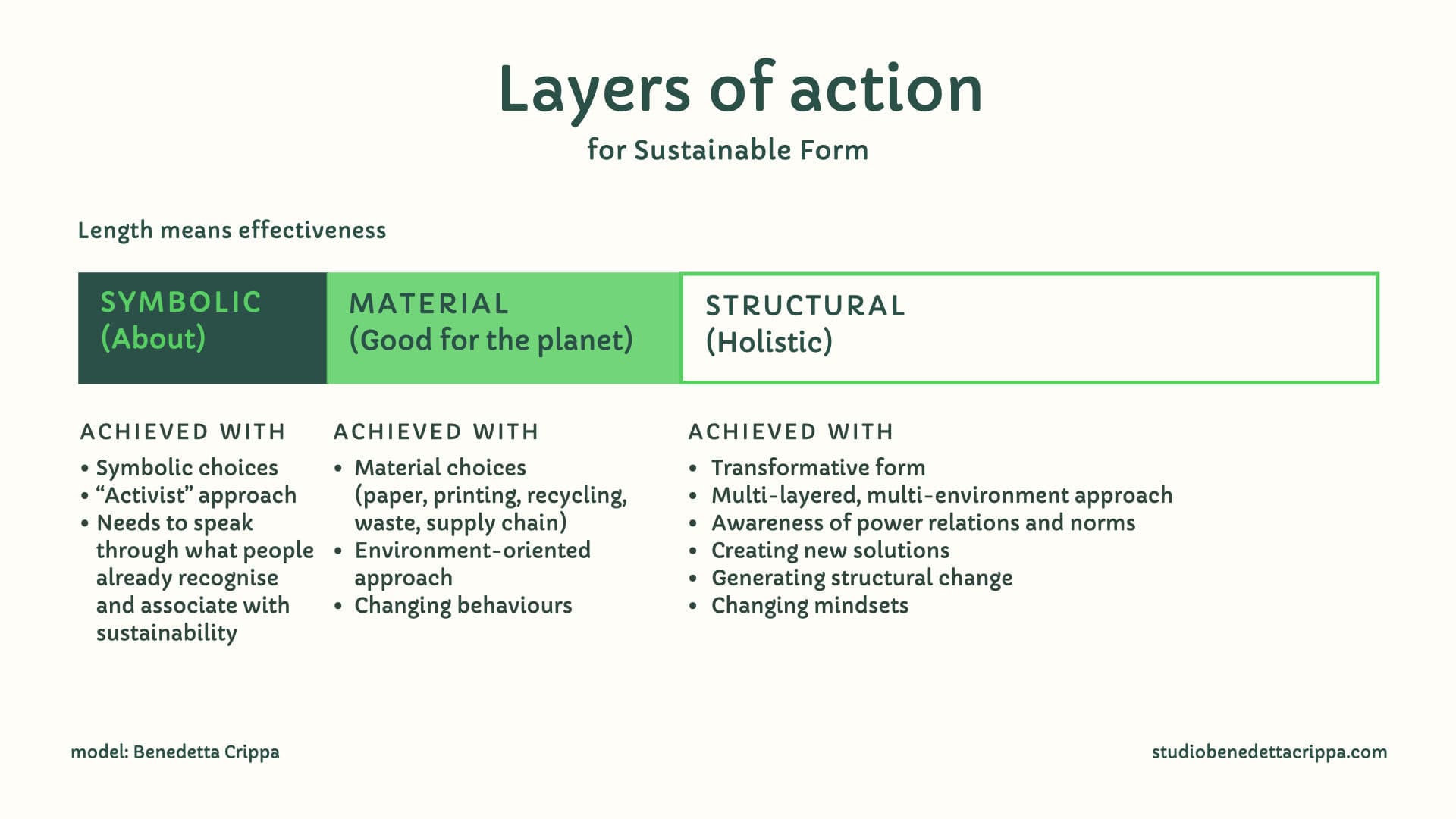

I would like to ask you about the chart “Layers of Action”. It’s really interesting that you classified those actions we can do as a graphic designer. To make it even clearer, could you give us a concrete example of those actions based on three layers?

The first layer, the symbolic one, is widespread in design. This layer can be useful at times, but it is not the kind of work that will lead to the kind of structural change we need. It’s the layer when we call attention to sustainability, we do something “about it”, in a way that can or cannot have application in the real world. The light bulb made of grass, the poster that forms letters out of car emissions are an example of this layer. It also includes design that focuses on sustainability in its methodology but not its output. Clients of graphic design have a million ideas that fall within this layer, because it allows us to “perform” sustainability. But it can be useful to call attention on something. Graphic design work that presents content “about” sustainability also falls in this category.

The second layer focuses on material reality. It focuses on things that can be quantified as sustainable and deal with the supply chain of a design. The book made of recycled paper, the chair made of second-hand wood, the website made to save energy are examples of this layer. This layer is important, but it stops at material considerations. Communicative and aesthetic considerations are beyond its reach, it reduces design as a question of calculations most of the times. Most dangerously, it considers aesthetic value as being against sustainability, which would erase most of the world’s visual culture. This layer also remains invisible to the user of the design unless it is declared. That is why we need ecological paper stamps, or other declarations that make the user pay attention to the choices that were made – the “green labels”.

The third layer is the holistic one, where the most visible layer of the design, its aesthetic and communicative qualities, are what we work with to propose alternatives to exploitative approaches to form. It means asking ourselves questions about power and exploitation when we design, and make decisions based on that. This kind of work is harder to measure and “point to”. It is whatever form that questions dominant traditions in a way that expands our capacity to co-exist with one another.

I often hear my fellow graphic designers say: “choosing recycle paper is the only thing graphic designers can do for climate while our income depends on the capitalistic industry”. Do you have any similar dilemma about it? Or have you found a way to think about your work differently?

Every day I deal with the reality of being immersed in a seemingly inescapable capitalist system, and every day my awareness of how much our economic system trickles down to every single choice that is collectively made grows. That said, choosing recycled paper is only one of many, many things that designers can do to address the climate crisis. If the climate crisis is caused by a mindset of exploitation (of the planet and of each other) then we must work with the root of the problem, and challenge exploitative mindsets through our form. There’s just so many ways we can do that. We can say no to clients that foster this exploitation, to start, and focus on helping who is working toward another way. We can educate ourselves about power and how it has impacted visual culture globally. We can decide to put our values front and center when we design. The rest will follow.

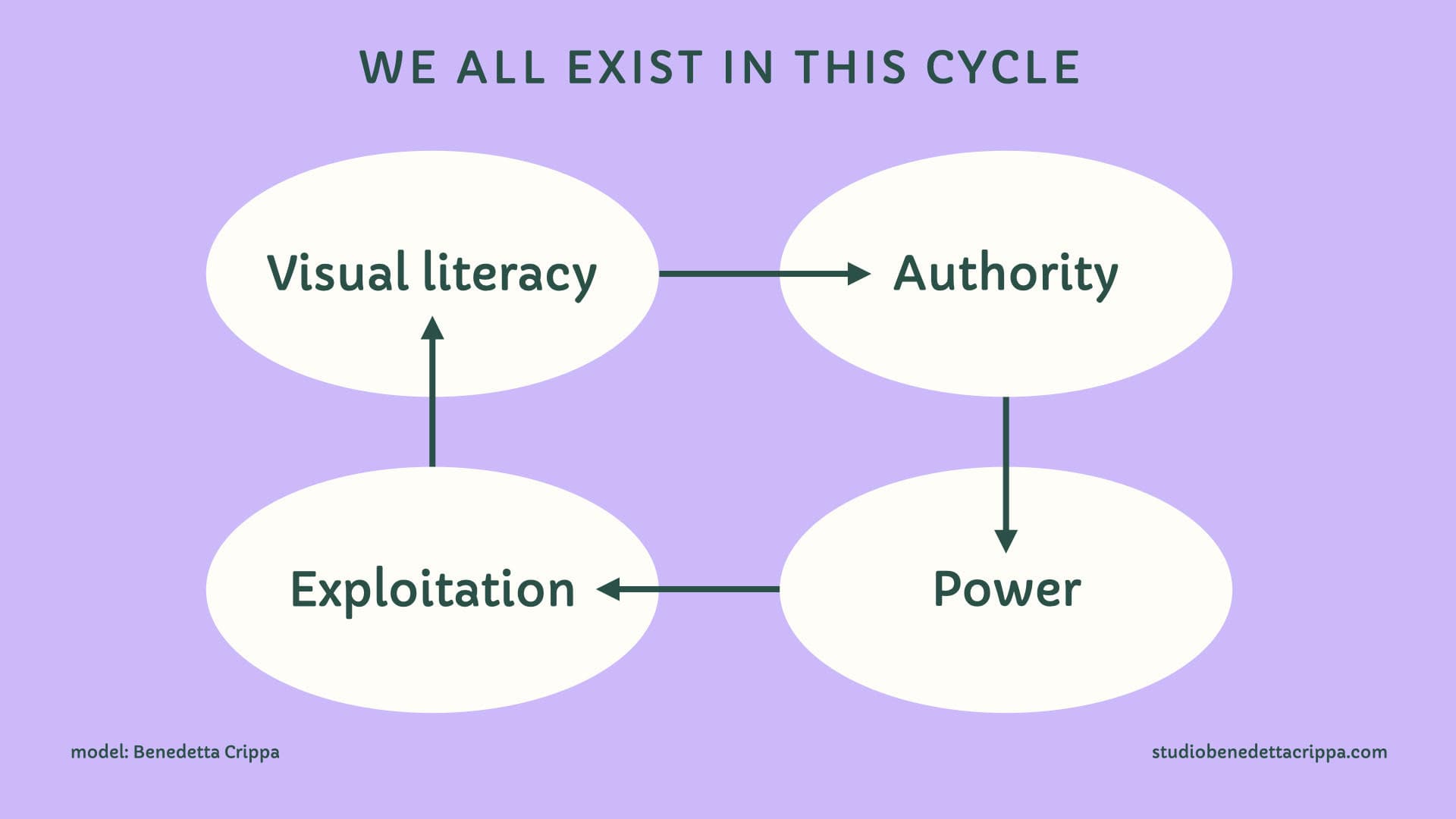

You’ve previously talked about the idea of “visual literacy”. I agree that the visual world that surrounds us today is mostly built upon the history of capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy and white supremacy. I also find uncomfortable expressions in graphic designs and advertisements from time to time. But it’s a huge issue to face for individuals. Do you think we could avoid being a part of this unsustainable visual world? And if so, how?

This comes down to the very core of what it means to be a designer. Being a designer means to have the task of showing another something beyond what already exists. We exist to never accept what is put in front of us, but to build upon and beyond that. That’s creativity. It’s our responsibility, our craft, it’s why we do what we do. This ‘unsustainable world’ was created by certain people in a specific period of time. It is not unavoidable, nor the best we can do. When people will tell you that this is the world we have and that’s it, ask them if they think this is the very best we can do and then observe their eyes. Endless parallel words start opening in their minds right there, all it takes is to suggest it. We all know there’s more than this, but most of us have stopped imagining it.

So my task is to propose that another way is possible and then attempt to show that through my work. Mind you, it has to be through my design work, not by taking a PhD in Philosophy (I love philosophy, just an example) or writing 100 books about decolonisation. It has to be through the visual craft. I do not think it is possible to avoid ‘being part’ of the world as it is now. We are all part of the same system. My objective is not to get out but to get through. I can acknowledge that I am here and that within that system I am going to do my best to show another way and go to bed at night knowing I am doing my best and I am keeping my integrity. It is not a choice. I have to believe I can and I truly believe so, it will just take some time, one has to be patient, one step after the next. If I would believe for a second that I am just destined to be a victim of the way someone else has defined the world for me, then I would not be a designer, it means I already lost.

Visual literacy could easily lead to a debate on cultural appropriation. At the same time, I’m aware that in many parts of the world, people still don’t have an opportunity to become graphic designers. Could you tell us what you think we (people who have an opportunity to be graphic designers) could do about it?

Let’s clarify what visual literacy means. Visual literacy means having a visual vocabulary, building the ability to decode, trace, interpret and analyse visual form. We all have a degree of visual literacy, and people that have visuality as their jobs have an advanced level of it. We have trained for it. That’s why a graphic designer can quickly pick one out of 100 typefaces when most people can’t even begin to see the differences between them. That is also why we can see connections that form creates and clients can’t, it’s our job. So, visual literacy has nothing to do with cultural appropriation, which is the practice of appropriating and using as one’s own visual expressions of other cultures without careful considerations on power.

So that said, graphic design as a profession is a “service” practice. It’s not agriculture, it’s not industrial, it’s fundamentally a service that can exist only in service-based economies. And it depends on a lot of other services – printers, web infrastructure, the paper industry, other artisans, clients giving work, and so on. When people are without food, you cannot have universities teaching graphic design (or web development, or business strategy for that matter). Many economies in the world are still agriculture or industry-based therefore not everyone in the world, unless they migrate, can become a graphic designer yet. But every culture in the world has a rich visual history. Similarly, communication is at the center of every human interaction. So although not everyone can be a graphic designer, everyone can build visual literacy, and work with visual communication. Visual communication has always existed, everywhere in one form or another. “Graphic design” is what we call visual communication established as a service, a profession, in service-based economies.

When we dig deep into climate change and its cause, it’s clear that various social injustices are interconnected. In this sense, I think your research is important for graphic designers who are concerned about climate and it will help them see a bigger picture. Is there any social issue that you care about apart from the environment?

My main starting point has never really been the natural environment. I have a strong sense of justice that to me highlighted social issues before environmental ones. I deeply care about arriving to a situation where as humans we can respect and celebrate one another beyond our differences. Women’s liberation from patriarchy is on the top of my list. Supporting with visual communication a women’s shelter in Nepal was my first job in the field of social equity. Working for youth busy with democracy building in Central Asia was second, an anti-racist organisation was third. The climate crisis stems directly from a fundamental mindset of disrespect and exploitation mainly carried out by men in richer economies against everyone else, and particularly against women and everything perceived as feminine (which includes a culture of care and respect, considered ‘weak’, naive). Solving the climate crisis will never be possible unless we address this systemic imbalance.

Program poster designed for the cultural programme on sustainable city development Artistic Undressings in Stockholm, courtesy of Benedetta Crippa.

To the graphic designers who have been wondering what they can do in the era of climate change, what would you say to them?

Educate yourself about power, get ready to revise your role in this world, put your values at the center of your work, use your work to elevate who has less power than you; structure your business in a way that it can continue to exist, believe you are needed, find teachers that raise your self-esteem instead of destroying it, and don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t do any single one of these things.

This interview is excerpted from With Dilemmas From the Future: What can graphic designers do in the era of climate crisis? by Minami Hirayama and is available to purchase here.