Editor’s Note: Kenneth Grange, the industrial designer and co-founder of Pentagram, died this month at 95. In memory of Kenneth, we are pleased to publish this edited excerpt from Kenneth Grange: Designing The Modern World by Lucy Johnston (Thames and Hudson). This excerpt focuses on Grange’s Pentagram years and we recommend picking up the book for a full accounting of his remarkable career.

The announcement of this high-profile new partnership, and the explanation of a proposed new working model for a design office, was met with curiosity and fascination by the industry—as was the chosen name, Pentagram, which, so the legend tells, was suggested by Alan Fletcher, who had been reading a book on witchcraft. This suggestion was thrown into the ring in jest after many hours of discussion and after Theo Crosby’s popular idea of Grand Union—suggested for the canal alongside the building and as a wordplay on this being “quite a coming-together of talent”—had been thrown out after someone pointed out it translated into French as “trade union.” As they would all later recall, the name Pentagram “just somehow stuck.”

At that point in the evolution of the design industry there were no other large, multidisciplinary design offices in the UK, and Grange described how they felt to be “stepping into a brave new world.” The anticipation and excitement for the potential ahead of them is palpable in the glamorous confidence of the five in their original press photograph. A launch feature in Design magazine explained that the desire to grow a bigger organization had originated with Fletcher and Colin Forbes as far back as 1962 when, on looking ahead twenty years, they “dimly perceived that big clients would be more interested in dealing with other organizations than with freelancers:” a prescient vision. Pentagram Design Partnership was officially incorporated in June 1972, and launched with a big party at the studio to which “every journalist and newspaper turned up, and all the great and the good.” Grange would later recall: “We just called up all the folks we knew. It was a great beginning and we never looked back from that, really.”

The building the partners leased, a converted warehouse adjacent to the Grand Union Canal and to Paddington Station, gave the five ample space to set up their individual sections; not least Grange, whose desire to increase the size of his workshop and model-making facilities had been the “deciding factor” for him in joining the partnership, having worried more than the others about the potential loss of individual identity. His substantial team, the biggest of any partner, situated itself at one end of the open-plan space behind a glass wall to shield the rest of the company from the noise of the workshop machinery; the glimpses of activity this offered would prove endlessly fascinating to the marketing executives and other clients visiting the more serene graphic design partner sections across the studio.

Grange’s department brought with it the strong camaraderie developed in Hampstead, with practical jokes a constant source of amusement shared between them—a form of wit Grange greatly enjoyed and appreciated, having inherited this good-natured sense of humor from his mother. The exceptional model-making skills honed by his team often proved central to the success of these jokes: on one occasion, the head of the workshop, Bruce Watters, fashioned a highly realistic lookalike of his own finger, finished with a bloodied end, which he popped into a matchbox and presented to Grange’s unsuspecting secretary, Elizabeth Burney-Jones, asking her innocently “what he should do with it.” Burney-Jones promptly fainted, but came to in good spirits. Grange remembers that attempts to engage the wider company in some of these escapades, including trying to convince Fletcher through a forged letter that he was expected to wear a kilt to an upcoming partners’ away-weekend, “went down like a lead balloon,” so the team learned to keep its comic efforts to itself.

The partnership approach of the new organization was open and democratic, considered an association of equals with each partner continuing to retain his own clients and run his own projects. The new factors were that administrative costs were pooled, each partner would receive the same income, and profits were shared, regardless of the value of projects that each partner brought in. By way of comparison, for similar income Grange’s projects had substantially longer timescales and were heavier on resources than other partners’ graphic design projects with shorter turnaround times. Regular partner meetings were held at which potential new clients and projects were discussed, and the benefit—or lack of—mutually agreed. The group would also take itself off for a long weekend of general strategizing every six months. The criteria for accepting a job into the studio were described as “cheerfully unrigorous:” a project had to be “either profitable or interesting.” And as long as the books were balancing, the partners would actively encourage each other to do non-paid or poorly paid work in order to build a rich and unusual joint portfolio.

Also unusual in the new organization’s set-up were the catering arrangements, instigated by Grange and which came to be legendary and an effective way of tempting clients into the building for meetings. Grange had often experienced the workers’ canteens and executive dining halls of his clients across the industrial sector, but for the other partners and for the wider design industry, which until now had seen only small studios, this was a novel concept. The partners introduced a culture of team mealtimes, installing substantial kitchen and dining facilities and employing a new in-house cook each year to keep things lively, the thinking being that not only was this democratic, sociable and good for team morale but commercially it also saved valuable time for the partners, who would otherwise be “out for lunch with clients most days.” Everyone ate the same menu and ate together, from directors to junior staff. And clients and other high-profile guests, who Grange recalled “loved the socialism” of this novel arrangement, would regularly be invited and were delighted to join in. Perhaps most importantly, it ensured that every member of staff had at least one square meal per day.

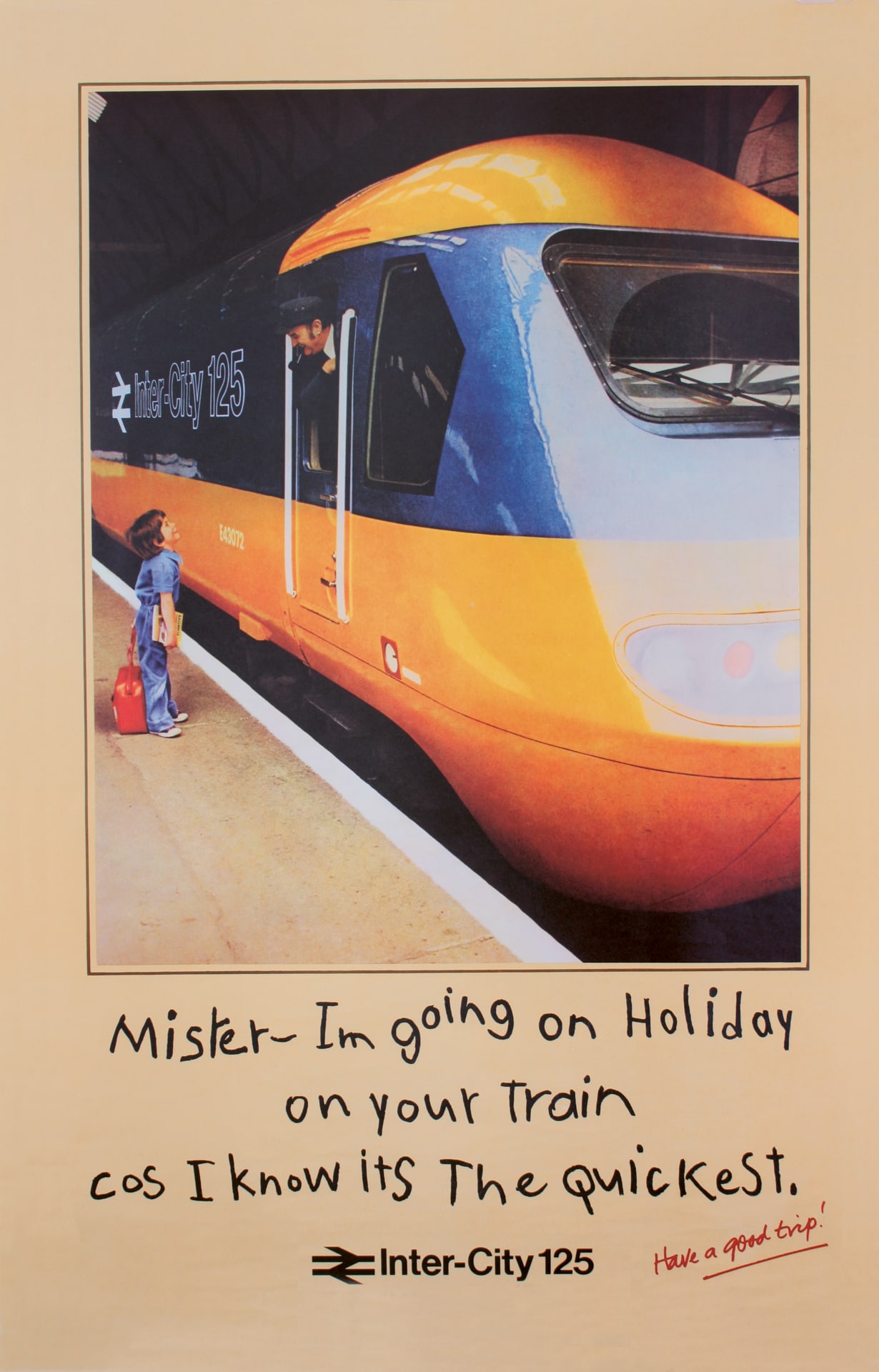

One of many promotional posters created by British Rail to promote the Inter-City 125 service, and one of Grange’s favorites. © Kenneth Grange archive. Courtesy of Kenneth Grange, Pentagram, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

By the late 1970s the profile of Pentagram as an entity was reaching new heights on the international scene. Particularly on the graphic design side, there was appetite to expand and, having been comfortably handling “a substantial chunk of American business in Europe,” in 1978 Colin Forbes, ever the businessman of the original five partners, saw an opportunity: moving to the USA, he set up a New York office, in the early days generously hosted by the renowned US designer George Nelson. From here Pentagram began its second chapter as “truly an international agency,” and not long afterwards, back at home base, the London contingent moved to new and more prestigious premises in Notting Hill as the number of partners and employees continued to steadily grow. The renovation of the spacious former dairy building on Needham Road was painstakingly masterminded by the architect of the partnership, Theo Crosby, with Alan Fletcher, and continues to be the home of the London office today.

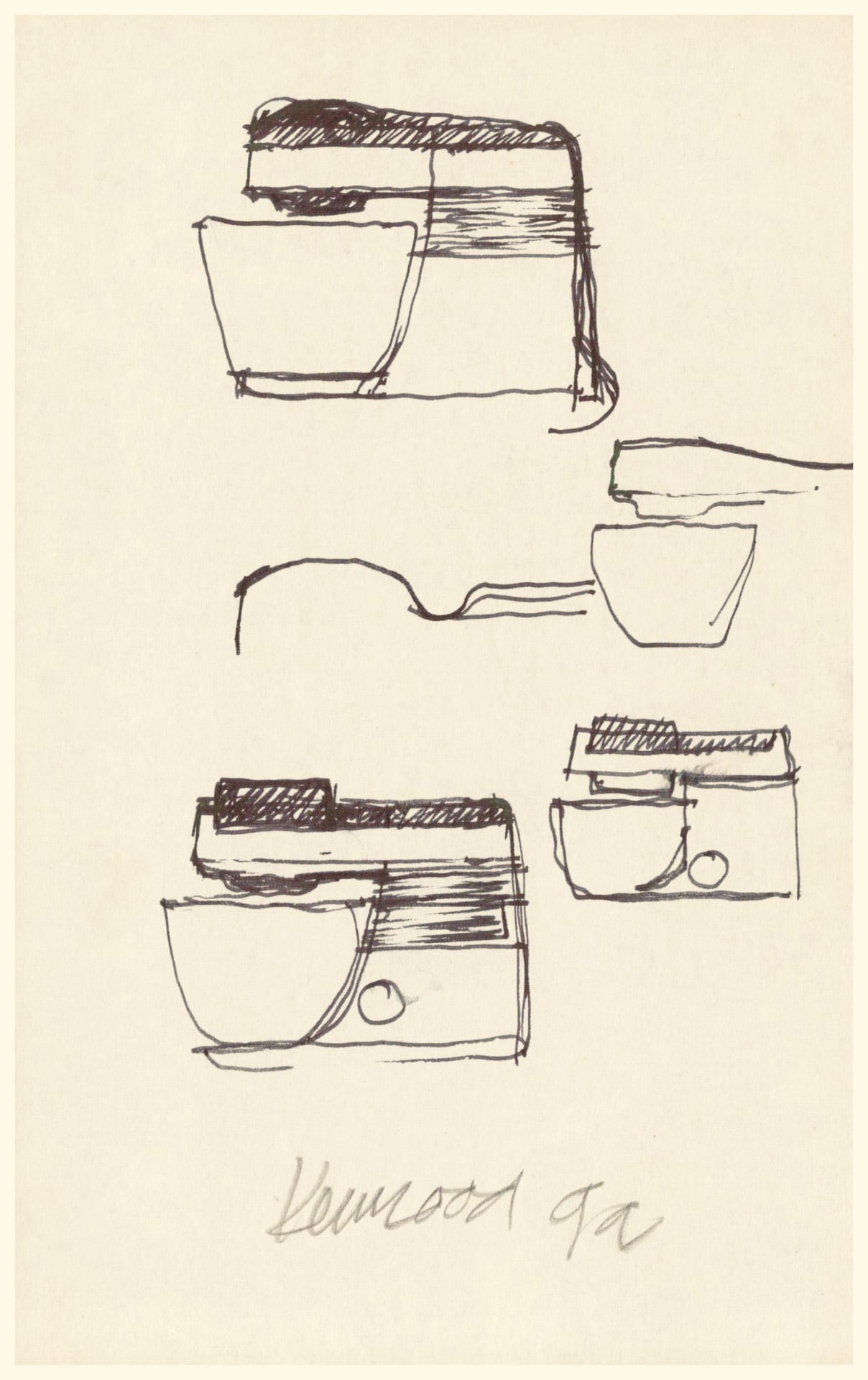

Meanwhile Grange was continuing to forge his own path within the studio; after the InterCity 125 burst onto the scene in 1975, and into the 1980s, his profile was reaching a peak. His early success designing loudspeakers for Bowers & Wilkins catapulted him into another new industry: the rarefied world of music recording studios. He seemed to be on every guest list as the design world jostled to host him, with a whirlwind of international speaking engagements taking him from Denmark, Finland and Russia to South Africa, Australia, India and Singapore. His attendance at trade shows was substantial too, the three biggest being Electronica, Domotechnica, and Hannover Messe in Germany, which he visited every year in his roles with Kenwood, Kodak and other clients. He also navigated numerous requests to join judging panels and the advisory committees of design organizations. Behind the scenes, if the mass of neatly penned entries in the appointments diaries is anything to go by, it was an impressive and meticulous military operation on the part of his secretaries and assistants to keep everything seamlessly rolling.

The first years of the 1980s brought with them a maturing of the consumer goods industries as a wider understanding of “how design can beneficially impact industry” was embraced and companies moved into an era of highly competitive, commercially focused manufacturing and design processes. This is apparent in Grange’s appointment to two consultant design director roles in quick succession—Wilkinson Sword and the Thorn EMI group, by then owners of Kenwood. A press release from Wilkinson Sword stated that “directorships command respect within a company, and the hope is that this appointment will have a beneficial effect on the design departments within Wilkinson.” During this period, in recognition of his wide-ranging experience across both design itself and the industrial design management process, Grange was also appointed industrial design adviser to the Design Council (previously the Council of Industrial Design), which had done so much to promote him during his own early career years and to which he would give much support in the following years. In his SIAD (Society of Industrial Artists and Designers) Milner Gray Lecture at the beginning of the decade, the British Rail chairman, Sir Peter Parker, would credit Grange’s part in embedding design in industry, stating that the successful InterCity project showed that “design management should insist in sharing the long hard look ahead; design management must be part of the strategic leadership.”

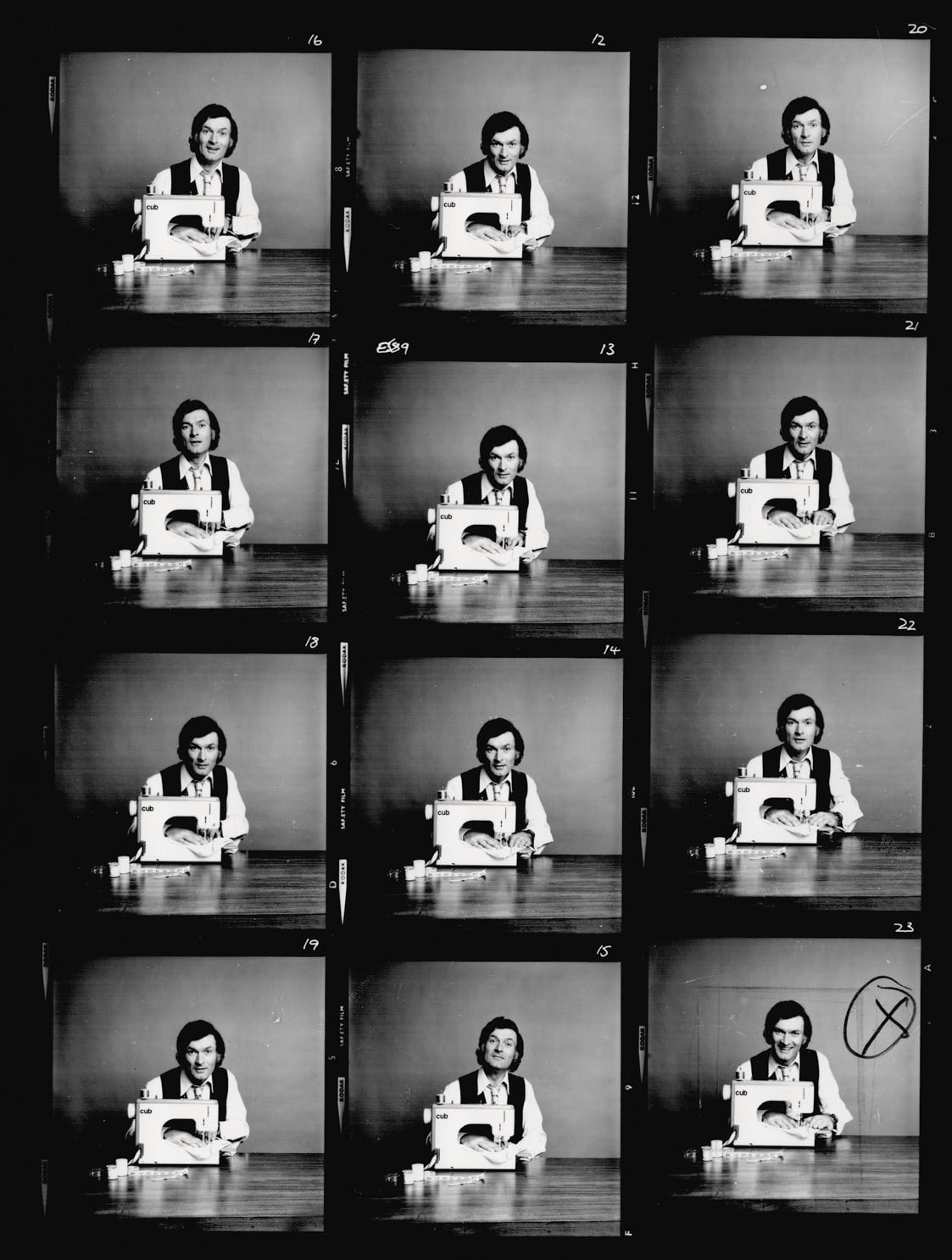

May 1983 saw his first solo show, remarkably the first complete show at the V&A dedicated to a designer during their lifetime, staged in the new Boilerhouse Gallery at the V&A, a project initiated by Terence Conran and Stephen Bayley, director of the Conran Foundation, which would later lead to the creation of the Design Museum. Titled “Kenneth Grange at the Boilerhouse—An Exhibition of British Product Design,” the exhibition was designed by David Hillman, a second-generation Pentagram partner of whose work Grange was a great admirer. The show consisted of a selection of product designs—Grange bravely including those that had been less successful alongside his big breaks, as an honest review of his evolving career; and in the accompanying captions and catalogue he spoke self-deprecatingly about the driver of “fear more than talent” behind his work. Bayley, who penned the introduction to the catalogue, stated that “it adds strength to a designer’s reputation when you hear him explain the reasons why some designs became lemons” and concluded that “it would be a very dull person who was not moved by the evidence of what a directing mind can do on the empty canvas of industry.” To mark the occasion, renowned photographer Anthony Armstrong-Jones, Lord Snowdon, shot a striking black-and-white portrait of Grange, now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Various sketches of the Kenwood Chef from Grange’s sketchbooks during further development of the product after his appointment to the company. © Kenneth Grange archive. Courtesy of Kenneth Grange, Pentagram, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Following this first solo show, Grange would later be similarly honored by the Japanese in 1989 with that country’s first retrospective of the work of a British designer. In the UK the recognition through the V&A was followed by the award of a CBE in Queen Elizabeth’s 1984 New Year’s Honours list “for services to design and British industry,” and not long afterwards a flurry of honorary doctorates followed from a number of British universities. And in 1985 he was made Master of the RDI (Royal Designers for Industry) faculty for a two-year stint, during which he focused on promoting the Master’s Medal to encourage young designers, a cause he continued to take up across other positions too, as well as encouraging a constant flow of student visits through the Pentagram offices.

One might argue that a particular peak in Grange’s profile was reached in 1986, which in the UK was dubbed by the government “Industry Year” and saw a mass of activity to “further promote understanding of the role of design in industry.” Design magazine explained that “as Britain attempts to reposition itself in world markets, there is a wealth of new opportunity for design.” Grange was involved in much of the activity, from speaking at the Design Commitment conference hosted by the Prince of Wales at Lancaster House to presiding over the “Eye for Industry” exhibition at the V&A showcasing the work of the RDIs, as well as helping to promote the exhibition “Thirty Years On” at the Design Centre, originally set up by the CoID in 1956, in London.

However, his activity that year was, in his mind, crowned by the results of a vast undertaking when, together with the renowned British furniture manufacturer Rosamind Julius, he co-chaired the annual International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado. The 1986 iteration of this highly prestigious event was titled “Insight and Outlook—Views of British Design,” commissioned in response to a boost in overseas demand for British-trained design talent, and saw Grange and Julius bring together a host of top names from across the spectrum of the British creative industries to deliver talks and set up showcases. Two years of graft and planning culminated in a complex week-long event of great acclaim, and the extraordinary coming together of so many key figures was considered “a unique coup” in the industry’s history. Guest speakers ranged from David Hockney and Ralph Steadman to Norman Parkinson and Christopher Frayling; apparently the only person who turned down the invitation was the “notoriously difficult” Malcolm McLaren. Grange described the flight out to Aspen, during which he “worked the aisle,” introducing everyone to each other: “it was almost a plane-full and most of them had never met before. It was an incredible buzz.” The event attracted sponsorship from the Department for Trade and Industry, the British Council and leading manufacturing companies, as well as collaboration from the Design Council and the Society of Industrial Artists and Designers. As Grange also recognized, the project saw generous support from Pentagram to assist the sizeable production and logistics.

By the end of the 1980s more than fifty per cent of Grange’s projects were based in Japan, where he found great satisfaction and pleasure in the work. Reviewing his comparative experiences of British and Japanese industry, when he later delivered the RDI Annual Address at the Royal Society of Arts on the subject of “Twenty-one years in Japan,” he said that “our manufacturers do not have the expansive attitude to employment of resources, and by that I mean energy and enthusiasm as well as money, which you get in Japan. The result there is sheer elegance, time and time again, wherever you look. It’s tremendously stimulating and I feel privileged to work in such a community.” And interestingly, following the great success of a meticulous, modular bathroom scheme for Japanese domestic tile company INAX, his last years working in the country would see him return to the origins of his career in the architectural industry, consulting on a sophisticated new prefabricated housing concept for the Tokyo-based developer Sekisui Heim: a vision to deliver design-conscious homes catering to the requirements of “three generations of family under one roof.”

Although he was spending the largest share of his working time in Japan, Grange still retained considerable involvement in projects for the USA and Europe, though these were increasingly being handled by his capable team. Of this era he spoke with gratitude both for his team and for the growing ubiquity of the fax machine, meaning he could keep abreast of projects while out of the office and also speed up the process of gaining approvals from clients. He explained how “we could chop up a drawing and post it through the machine in pieces” rather than having to wait days to see it if it was mailed or him having to “forever exist on planes.” He reminisced about how “it’s extraordinary now to think back to the days when my secretary might say to a client, “Mr Grange is away on business, he’ll get back to you in three weeks.’ The pace of business just wouldn’t accept that now. You’d be out of the game immediately.”

By the early 1990s, while he was still ever prominent as a spokesperson in the industry, Grange was noticeably starting to hand the baton of responsibility for managing projects to his team, some of whom had been with him since the earliest days of the office in Hampstead. Notable among these shifts was the appointment of one of the senior designers, Johan Santer, to an internal design management role within Kenwood. With Grange’s agreement the company had by now set up an in-house design agency, rather than outsourcing consultancy as much as they once had—a move that was becoming increasingly common across the industry—and Grange handed the reins to Santer with his blessing. This brought to a close an exceptional client relationship that had seen him through from his earliest days as an independent designer back in the late 1950s.

The 1990s was also a time of radical change in the working processes of the studio at Pentagram and in the wider design industry too, with the gradual introduction of desktop publishing (DTP) and computer-aided design (CAD); for Kenneth’s team particularly this change was driven by the requirement to keep up with the preferred practices of their clients. Although he himself never felt that he needed to learn to use the software, and the investment in the Pro-E software for industrial design of that era was a very costly consideration, Grange accepted that the format of the studio’s output needed to evolve and encouraged his team to take the steps needed towards meeting these requirements. At first a shared “corral of technicians” was introduced into the center of the studio, while later this was gradually replaced as young designers already proficient in the necessary skills joined the design team.

The changing technological times were also reflected in the later project commissions coming into the studio, which started to include early mobile phones and personal computing and other increasingly advanced digital products. Although these jobs excited him less than they did the younger designers in the team, Grange appreciated the value of his lifelong learning across the spectrum of technology, fabrication, and working processes; when in 1996 he was awarded the inaugural Minerva Gold Medal in recognition of a lifetime’s achievement in design from the Chartered Society of Designers, the body he had first been elected to join as a fledgling designer in 1955, he reflected: “In my career I have found that pretty much everything I have learned has been given to me by my clients.”

The following year, 1997, brought round the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pentagram, and was a time of introspection and review as well as celebration for Grange. The studio had mourned the death of Crosby a couple of years previously, Fletcher had retired in 1992, and from its original vision Pentagram was becoming a more commercially savvy, competitive organization in a fast-paced global industry; the company now had a wide array of partners installed across multiple international cities. It was at this milestone that Grange decided it was time for him to start his transition away from Pentagram and return to practicing as a smaller, independent studio.

Feeling a yearning to distance himself from the constant pressure and intensity of it all, he wanted to “get back to simply focusing on making things.” It was also late in this time at Pentagram that he employed Daniel Weil, a product design graduate, and later tutor, of the RCA (Royal College of Art), whom he had happened to critique during his finals, and to whom he would eventually hand responsibility for the industrial design division of Pentagram along with a recommendation that he be made a partner.

Grange’s last projects delivered while at Pentagram included a rural postbox for Royal Mail and, arguably a fitting swansong, an acclaimed design of the new-look London taxi cab, the TX1. The renewed fame this brought both in the industry and in the public consciousness were a well-timed boost to him on his way to reinstating Kenneth Grange Design as an independent practice. In early 1998, at the age of sixty-nine, Grange finally extricated himself from the “Pentagram swim” and—taking with him just a few favorite clients and a couple of his closest Pentagram team—embarked on another new chapter in his career. Naturally, for Grange, there was to be no such thing as retirement.

© Kenneth Grange archive. Courtesy of Kenneth Grange, Pentagram, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Excerpted from Kenneth Grange: Designing the Modern World, by Lucy Johnston, Foreword by Sir Jonathan Ive. © 2024 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London. Text © 2024 Lucy Johnston. Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc, www.thamesandhudsonusa.com