New Looking Out for Pleasure

In 1979, the British band Gang of Four released their first album entertainment! Both the band’s name and record title were wryly ironic. “Gang of Four” was more than a clever play on the number of members in the group, it was to deliberately evoke the notorious faction of Communist Party officials blamed for the excesses of the Chinese “Cultural Revolution.” Calling themselves Gang of Four (suggested by a then-member of the similarly provocative band Mekons) signaled that social and political engagement was prominent in their songs, more so than what was commonplace in the punk and post-punk bands of the era. The music was compelling in its brain appeal along with its aggressive danceability.

Gang of Four taunted expectations of punk, popular music and political content. Over a funk and dub inspired rhythm section, vocals shunned soothing melodies and placatory rhyme schemes (e.g. “He fills his head with culture/He gives himself an ulcer”), with declaimed lyrics counterpointing scratchy and staccato bursts of electric guitar. “Culture, entertainment, and advertising, [Gang of Four singer Jon King and guitarist Andy Gill] felt, had become one; capitalism permeated every aspect of human relations in a world where people want what they get and not the other way around,” wrote music journalist Michael Azzerad in liner notes to the CD reissue of entertainment! The band’s viewpoint was informed by Situationist Internationalist theory and actions.

The group’s agit-pop targeted a range of social ills, each ultimately confronting the lure and pitfalls of desire: interpersonal, social and economic, all while holding contracts with record label giants Warner. Bros in the U.S. and EMI for the rest of the world. How to reconcile this incongruity? Said drummer Hugo Burnham, “What’s the point of preaching to the converted? If we have something to say, why not say it to a million people rather than 400?” However, their musical choices when recording the album eschewed chart-topping moves. It pleased the band that EMI complained that the finished album sounded like demo recordings as opposed to a final polished product. Sonically, the record was arid, close-miked and claustrophobic. The agenda was to be real, immediate and uncompromising.

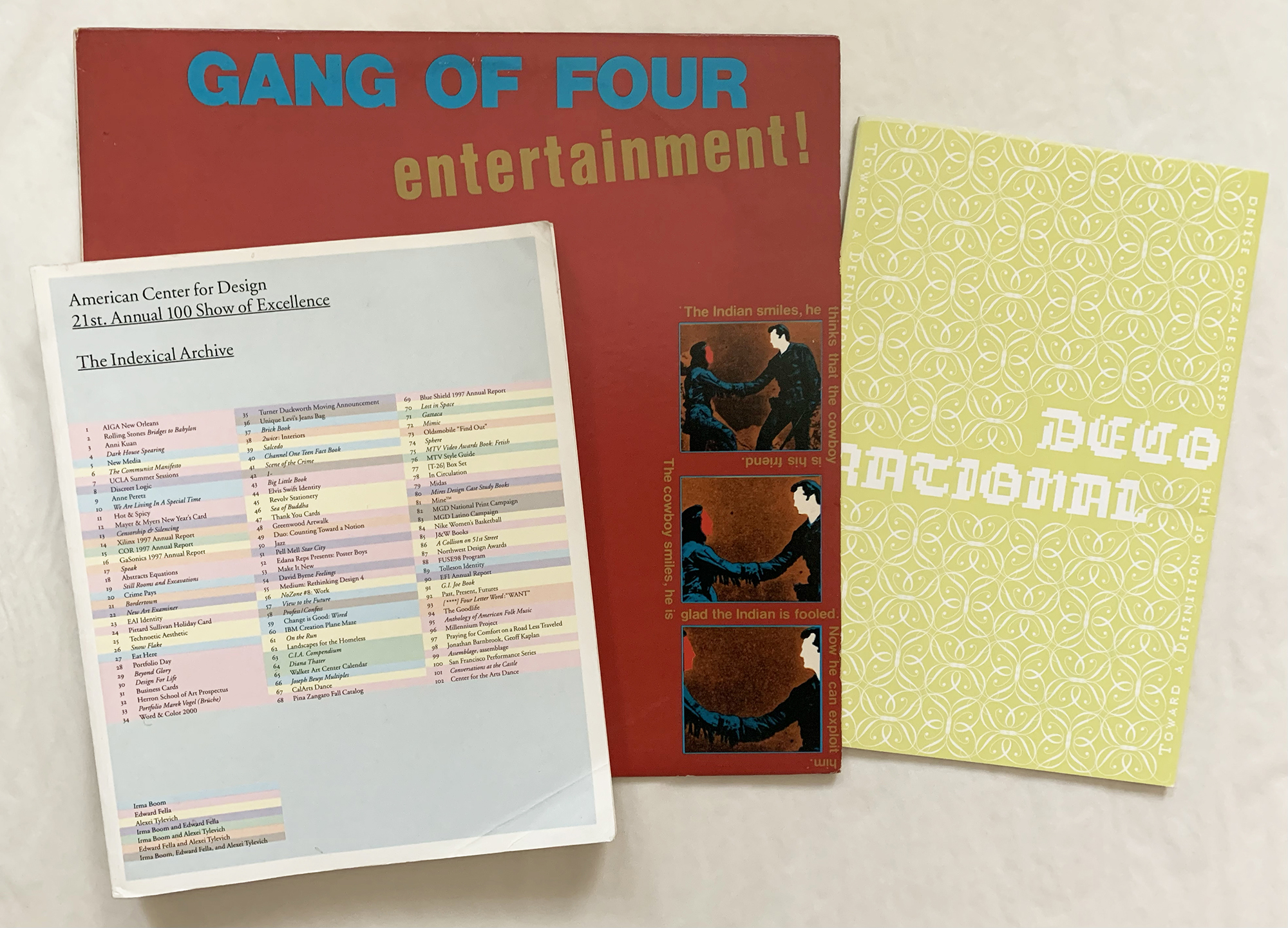

entertainment!’s cover design by lead singer and primary lyricist Jon King similarly deals in oppositions and understanding. The flat hues are a step down from the common punk LP identifier of florescent colors—think Jamie Reid’s lurid yellow-green and pink for Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s the Sex Pistols. While basic, the artwork isn’t inartful and far from naïve. It’s further in keeping with the post-punk aesthetic of being a do-it-yourself design job. Most of the cover is given over to an expanse of dark dull red. The choice is attention-getting and not coincidentally associated with Marxist and socialist exploits. Centered at the top edge is the band’s name set in all caps in a default bold sans serif. Its blue coloration causes a slight strobing between the contrasting hues.

The standard album cover ploy, especially on a debut, is to showcase and build the identity of the musicians by presenting them in a group photo. With punk and post-punkers, that was often inverted by relegating portraits to the back or inner sleeves. As with entertainment!, the bands sometimes shun appearing altogether to defy convention and cultivate mystery.

If the cover’s purpose is to represent the music, entertainment! does so directly, though obliquely, for packaging custom. Playing out on the right side of the cover is a three-frame stacked sequence of a “cowboy” shaking hands with an “Indian.” The image is a poorly reproduced still taken from an obscure film. Featureless, both figures are denoted in stereotyped color: the “cowboy” is stark white, the “Indian” bright red. In spirit, they are po-faced Colorforms. The second and third frames successively zoom in on the gripping hands in the center of the frame. Type slides around the frame edges, providing captions: “The Indian smiles, he thinks that the cowboy is his friend./The cowboy smiles, he is glad the Indian is fooled./Now he can exploit him.”

The text could easily be lyrics taken from one of the album’s songs. The “narrative” continues on the back cover, which is given over to an uneven grid of rough-edged frames like splotchy paint. Images depict a family whose father says, “I spend most of our money on myself so that I can stay fat”, while the mother and children admit, “We’re grateful for his leftovers.” Two stacked frames to the right provide the track listing.

The design’s crudity is deliberate and knowing, reflective of the punk D.I.Y aesthetic and album packaging tropes. But the key element of the album’s overall design satire is the title treatment. On the cover, “entertainment!” is set in all lowercase in a condensed version or slight variant of that used for “GANG OF FOUR.” The title is set beginning roughly halfway under the band’s name at a jaunty upward angle beyond “FOUR.” It’s a smirking invocation of advertising hype of “NEW!” “IMPROVED!” ilk. If the graphics’ rejection of typical LP styles has you questioning what you’d be getting with purchase, it’s also a bland reassurance of genre.

The design element highlighting the cultural complicity and contradiction of “entertainment” is the exclamation point. Here, the terminal mark is doing more duty than emulating generic product grandiloquence. The punctuation both acknowledges and challenges conceptions of both “entertainment” and “resistance.” How transgressive can the sincerest protest song be? Does making it “attractive” undermine, if not outright contradict, the message? Isn’t all culture—art, literature, performance—at a remove from lived experience and artificial?

The Dirt Behind the Dream

The attitude toward “entertainment” can be one of suspicion, especially among performers. There’s resistance to being an “entertainer.” Entertainment is seen as a separate, overarching category within culture; one that includes alternate versions of all the arts. It’s seen as something synthetic and contrived: impure. “Entertainment” sanitizes, simplifies, and is escapist. The customary description is “Mindless entertainment.”

This was pronounced among punk and post-punk musicians who were rebelling against corporate rock. Music had become adulterated with interminable guitar solos, orchestral accompaniment, elaborate costumes and stage shows, songs about faeries. And Eagles. And disco. Not all punk/new wave groups scorned each item in that list but all aspired to a direct and unfussy presentation. Bands’ stagecraft became bare bones. Paste up your photocopied fliers with magic marker and Dymo Label Maker typography. Show up, turn on the lights, and play.

As they gained in popularity, bands struggled with their relationship to their expanded audiences and their own desire for growth. On the whole, they came to terms with it. Talking Heads, for instance, went from performing in street clothes under house lights to the costumed, prop showcase of Stop Making Sense. In her notes for the Talking Heads’ compendium Sand in the Vaseline (titled after and sporting an Ed Ruscha painting on its cover), Tina Weymouth wrote, “Immeasurable thanks to all the singers and musicians who taught us what fun it can be to be an ‘entuhtainuh.’”

A guarded attitude toward being called an entertainer isn’t universal. Many performers embrace the designation, finding within it an affirmation and expansiveness. It transcends category and media, pointing up a positive characteristic of the person. Cedric Antonio Kyles incorporated the term into his professional identity, though like “Gang of Four,” it originated from an outside source. Kyles was performing at a show where “the MC referred to everyone as a comedian.” “But I sang when I got onstage, I did poems. I would do anything to fill up my time,” Kyles told the podcaster Jalen Rose. “I said, ‘Don’t call me a comedian, call me an entertainer.’ [The MC] called me Cedric the Entertainer. I had a killer show and got a standing ovation. When I came off, he called me Cedric the Entertainer again, and I just kept it.”

“Entertainer” in the context is expansive and assertive with a throw-back vibe. Graphic designers often grouse about the fuzziness of their appellation and haven’t enjoyed the old-timey terms assigned to them. But if what was once uncool becomes cool again, “Kenneth the Commercial Artist” could be a route to regard. Still, while considering the popularity of graphic design’s typical rhetoric regarding their activity, I’m not expecting to encounter a practitioner sporting “Paula the Problem Solver” anytime soon. To tart up “graphic designer,” the field affected the verb-to-noun exchange to dub themselves “creatives.” Unfortunately, musician Tyler Gregory Okonma has already claimed “Tyler the Creator” as his performative tag.

Sell Out, Maintain the Interest

While “entertainment” isn’t an association made with graphic design, engagement—gaining and holding audiences’ attention—is a common consideration for design products. Designers want audiences to entertain the ideas we’ve put into form.

Might we be better served to call ourselves entertainers or producing entertainment as our genre? The contemporary climate appears to welcome such a move. Design history, though, runs against association with gratification. Not only was ornament pleasing, but it was also criminal. Modernists claimed to have dispatched rhetoric—emotional appeals, if not outright appeal—from design making. However, they merely substituted their preferred, minimal aesthetic. Is it entertaining? I don’t pore over big books of Josef Müller-Brockmann’s work to be bored but your rapture may vary. High modern Swiss International Style was a bracing palate cleanser for design culture but as permanent fare, it wasn’t sating.

Concepts of neutrality and rationality dominated design for decades and still hold sway within and without the discipline. Post-modernism challenged binaries, collapsing supposedly sacrosanct categories such as “high” and “low” culture. “Entertainment” had more than a whiff of the latter—especially in exponents such as Entertainment Tonight. But its pervasive and persuasive forms—films, popular music—have long been celebrated as profound exponents of culture. The trash wasn’t taken out, it was brought in.

Not that entertainment had an unblemished rep, especially with the postmodernists. Guy Debord’s 1967 The Society of the Spectacle wasn’t posing entertainment as a respite from the simulacra and Neil Postman’s landmark 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business was no more laudatory. Postman’s target was television, which designers contribute to in their typical supporting role but they can find solace in Postman’s exaltation of print typography.

In the face of these two arguments, casting design as entertainment seems a losing proposition. Or is it? Establishing our coordinates on the big wheel of culture, determining where we’re situated in its simultaneity, makes resolving if design-as-entertainment is a denigration or exaltation. In the spin we’re in, it may be a win. Or, maybe both.

The Happy Ever After (Is at the End of the Article)

The post-postmodern world is one of hybridity of media. Forms such as “edutainment” and “infotainment” are long established, with once-discrete forms fusing with the methods and means of entertainment. We’re so far down this road, we can just detach the “tainment” taint.

Andrew Blauvelt addressed the implications of hybridity back in 1996 with the expansive essay “Unfolding Information” published in Emigre 40. He examined portmanteau media such as infotainment, and the need for new forms to represent our new circumstances. His final section considered an “erotics” of information. Blauvelt noted how pleasure had been leached from design to make it “serious.” Lost were audiences having any interest in or personal engagement with the “information.” In other words, it wasn’t entertaining.

Blauvelt appeared to obliquely demonstrate his thesis in action in 2000 with “The Indexical Archive,” the catalog for the American Center for Design’s 21st Annual 100 Show. Blauvelt’s approach was to present the same information in multiple layouts with slight changes in emphasis, one after another without explanation. It was a deadpan comedy of information design run amuck, or of indecision. As individual presentations, the variations were unassuming, blandly functional. But humor arose from their iteration, a graphical punch line repeatedly delivered. “The Indexical Archive” was a one-off, unlikely to be repeated (stop me if you’ve heard this one before). Blauvelt generated what might be the ultimate design in-joke, or major meta. Design-based humor otherwise rarely goes beyond “stunt typography”—like using Comic Sans ironically.

Blauvelt was specifically focusing on information design, an area particularly and deliberately parched of pleasure. This dry dream gradually desiccated much of design. In response, contrarian forces flooded the zone with all manner of heresies, such as finding ornament righteous. Denise Gonzales Crisp coined the suitably hybrid term “Decorational” with a manifesto of graphic sense and sensuality. Sporting the title “decorationalist” takes some unpacking where “entertainer” doesn’t.

What benefits are there to declare ourselves entertainers? It’ll be a slog for most, struggling against that current of “problem solving” determinism that designers unleashed on the world. For others though, it may align easier with public perception. It’s another unintended consequence of a broad societal awareness of design. Outside the profession, sensibilities and appetites for design have been facilitated and honed by phenomena such as pliant software, on demand publishing, and customizable websites. Design is a leisure entertainment option like scrapbooking. Fonts are fun!

For designers, no change in practice is required. It’s not an issue of becoming entertainers. We’ve always been there. Design history itself is a dramedy of pragmaesthetes searching for an identity. To our credit, we’ve largely fluxed over time and got with the zeitgeist. Entertainer or not, at least we get to keep “creative.”